A thick fog blanketed Woods Hole on the morning of Saturday, June 1st as my husband David and I drove to WHOI to meet eight students riding down from the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown. I was reminiscing about where I was this time last year—on a plane heading for Iceland for a research cruise to deploy some moorings east of Greenland (see past blog entries for more details if you're interested). Because of that cruise, I had missed the annual field trip to WHOI sponsored by the Perkins Outreach Program. I knew we had a great set of activities lined up for this year’s visitors, but I was still feeling a little nervous—it had been more than a year since I had presented my research to a group of blind and visually impaired students. Would I still be able to relate to them? Explain my work clearly and in an accessible way? My colleagues Andree, Carla, Megan, Heather and I had been working over the past few weeks to construct some maps and activities that would be accessible to a student with little or no vision. Would they work? Would the students be interested in the deep ocean currents that we would talk about with these materials? With my new duties as chair of the Physical Oceanography Department at WHOI, I hadn’t had as much time as in the past to think over what I would say, so, I hoped my past experience and instincts would help me out.

The students and their chaperones arrived right on time at 10 AM, and we got underway with the program. After introductions all around, the students divided up into three groups and rotated through the first three activities of the day: a tour of cool oceanographic equipment on the dock plus historical and modern-day scuba diving gear, an activity on harmful algal blooms, and a chance to check out the latest version of an accessible comic book about a squid named Neah and a grouper named Rusty. I followed one group around to all the stations, and learned a lot myself!

Then we were all ready for lunch, and a quick walk to the park next door where there is a touchable Statue of Rachel Carson, who visited Woods Hole in her early career as an environmentalist.

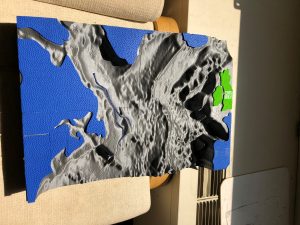

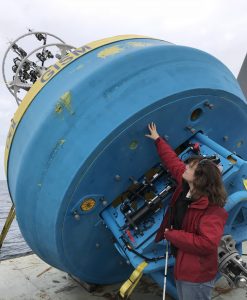

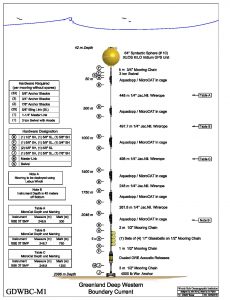

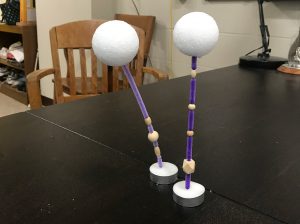

For the afternoon activity, we tried out our new lesson on deep ocean currents in the North Atlantic. We used three kinds of tactile “models”: a 3-D printed map of the shape of the North Atlantic’s ocean floor, miniature models of a drifting buoy and two sound source moorings used to track the buoys, and a simpler tactile map of the North Atlantic for each student to work with. The individual maps all had a tactile drawing of an arrow showing the most expected path of a cold, deep current in the North Atlantic called the Deep Western Boundary current. It is usually thought that this current flows southward from the Labrador Sea (located between Greenland and Labrador) along the western boundary of the North Atlantic, all the way to the equator and beyond. Back in the early 2000s, my colleague Susan Lozier and I put a large number of deeply drifting buoys in that current east of Newfoundland to see if that typical current was really the only pathway for these cold waters, or if there might be other pathways that no one had observed before. We discovered several new pathways that carry the cold water away from the expected path along the western edge of the North Atlantic and into the wide open ocean. Some of the buoys—also called RAFOS floats—were caught up in swirling masses of water called eddies, and the floats looped around and around inside these eddies for months. Other floats were entrained into a current going in the opposite direction, and followed a path back toward the north.

We showed the Perkins Outreach students all the various pathways that we discovered using pipe cleaners and wiki sticks, and then asked them to re-create those pathways, or make up new hypothetical ones, on their individual maps. While they were doing that, I explained how the floats are tracked underwater using sound, and illustrated the typical pathways using wiki sticks stuck onto the 3-D model of the North Atlantic. I think the students especially enjoyed learning about how sound—an environmental feature that they depend on more than most people, is used frequently for ocean exploration.

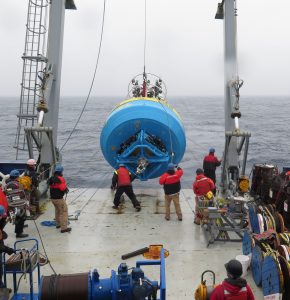

Then it was on to the highlight of the whole day—a trip out to Vineyard Sound on a charter fishing boat to have some first-hand experience at sea. Rob Reynolds of Zephyr Education Foundation was our host and teacher for this 90-minute voyage. The fog was still wafting in and out, but part way through, the sun came out full force and warmed us all up. Rob demonstrated how a hydrophone picks up the sounds of the boat’s propeller. The students then helped lower over a small dredge to see what we could pull up from the bottom. To everyone’s surprise, all we got was seaweed! Luckily, Rob had on hand a collection of live marine organisms like a lobster, mussels, clams, and sea stars for the students to touch and explore. There were lots of ooo’s and aaah’s, and a couple of screeches too, when a squirmy spider crab tickled the hand of one of the chaperones!

Perkins Outreach students help Rob Reynolds of Zephyr Education Foundation lower a dredge over the rail on our chartered boat.

Back on the dock, there was just time enough for a group photo, and then the Perkins students were on their way back to Perkins School. I thoroughly enjoyed meeting the new students, and greeting some repeat visitors again. My colleagues and I benefited immensely from the feedback we received on all our activities, which will help us make them even better next time.