Susan Humphris, Sharing Science Beyond the Sea

by Brett Freiburger and edited by the WHOI Women’s Committee

“Kids view the ocean as a fun place to go but don’t realize how it connects our world. They need to understand the importance of our oceans and how to preserve them.”

–Susan Humphris, 2004

Over the 90 years since WHOI was founded , women have made incredible contributions to the Institution and to ocean sciences. As our knowledge of the deep has grown, sharing advances and educating the public is increasingly important . Susan Humphris, a marine geo chemist at WHOI, is not only a world class researcher, but a key player in expanding how ocean research is shared with a wider audience.

Early Days

Susan’s parents were a dentist father and a mother who made “sure our lives were good, and we were secure and happy.” Living in the United Kingdom, the sea was never too far, but it wasn’t until her father began work for the Somerset schools, that the family settled in Burnham-on-Sea, where they “lived right behind some sand dunes very near the beach.” T his is where Susan’s passion began to develop. She learned to sail, participating in weekly yacht races. The family had a small boat to sail together, though extreme tides left only a few hours a day to retrieve the boat from the mud. Susan began to learn the importance of the natural world during this time. Interested in all subjects, except history (“I think it was the way it was taught”), Susan’s formal education was supplemented by family walks through the woods.

“During the walk, we’d stop and I had identification books for birds and flowers and trees, and we’d sometimes pick a leaf off a tree and take it back and look it up…”

These hikes developed her interest in nature and sparked observation skills that made her a world class researcher. “I certainly credit my parents with helping me.”

Throughout school, Susan was most fond of the subjects that gave her the greatest challenges – the sciences. When applying to university, Susan kept this in mind and decided that she “didn’t want to do just pure chemistry or physics.” Her love of nature directed her towards a focus that allowed the application of science to the environment and most importantly she “really didn’t want a career where [she] would be in a lab all the time or sitting at a computer all the time.” Only two institutions offered her such an option in an Environmental Sciences degree: the University of Lancaster and the University of East Anglia. Lancaster won out. With her small cohort of less than twenty students, Susan Humphris gained the experience and exposure that pushed her towards oceanography and on to Woods Hole.

At the end of her time at Lancaster, Susan started looking to the United States; a process she found rather difficult in understanding from England (“There was no Web or anything; I just had a paper catalog”). A lecture by Alex McBirney from the University of Oregon led to a very important tip. “I asked him for his advice as to where to apply…and he basically said to me, ‘Don’t apply to Scripps. Apply to Woods Hole,’ and his reasoning was that, at the time, a lot of the scientists from Scripps were moving to MIT.” Susan applied and waited…and waited….and waited, until months later, while figuring out her next move, the letter from the MIT/WHOI Joint Program arrived. Susan was accepted and suddenly “faced with the concept of ‘Wow! This means I have to go!’” Two weeks after her 21st birthday, Susan left England for the United States.

Coming to US and SEA

Adapting to a new country with a radically different approach to education was, at first, difficult for Susan. The British system she was familiar with had more independence, where one was expected to do the work then be tested yearly. The constant homework, quizzes, tests, term papers, made her “feel like I was in kindergarten again.” Also, she believed she “was being singled out for ‘special treatment’ because [she] had not come through what was considered a traditional basic science university program.” This feeling however subsided once Humphris made the move to Woods Hole after her first year at MIT in Cambridge. Struck by both the beauty and parochial nature of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Susan knew she was on the right path.

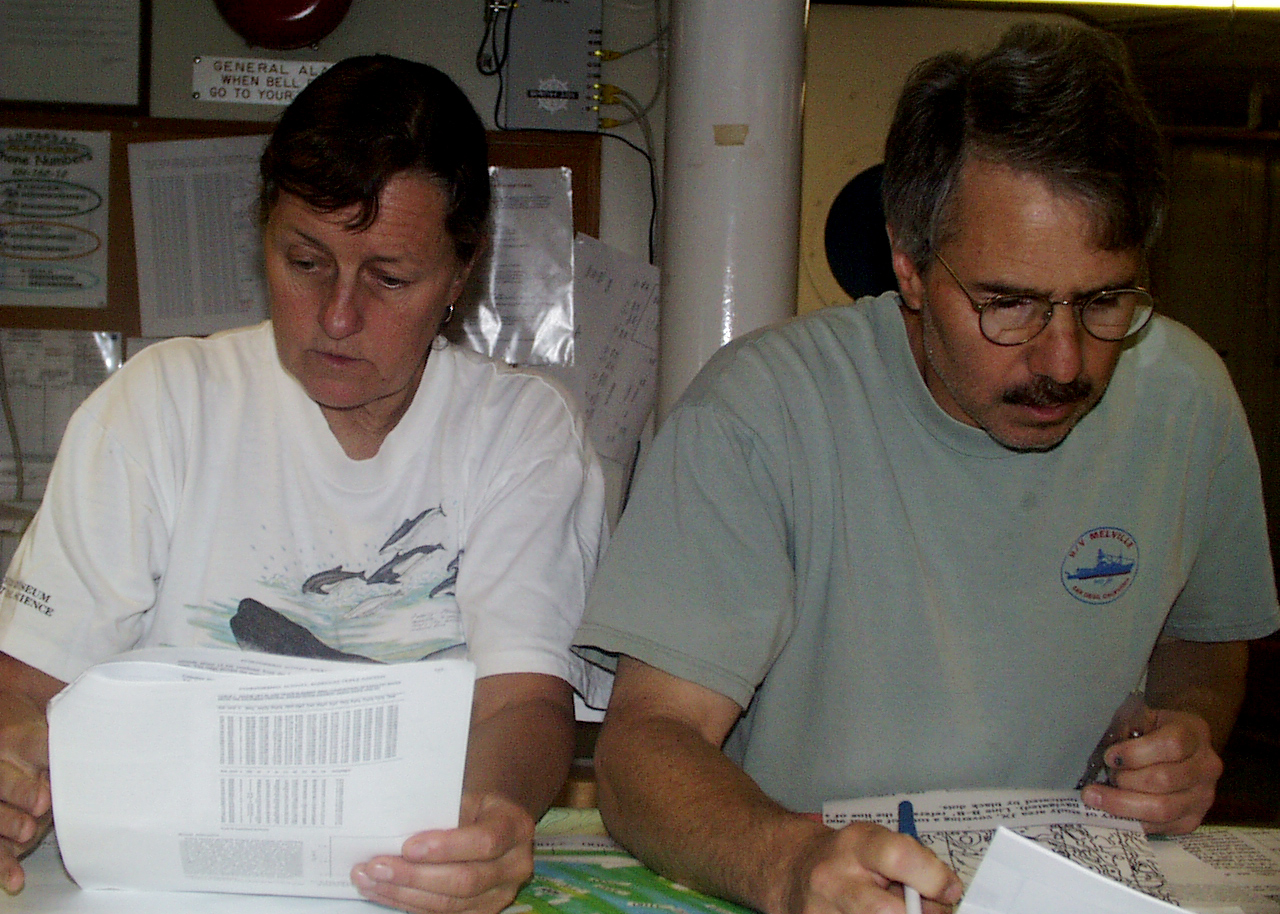

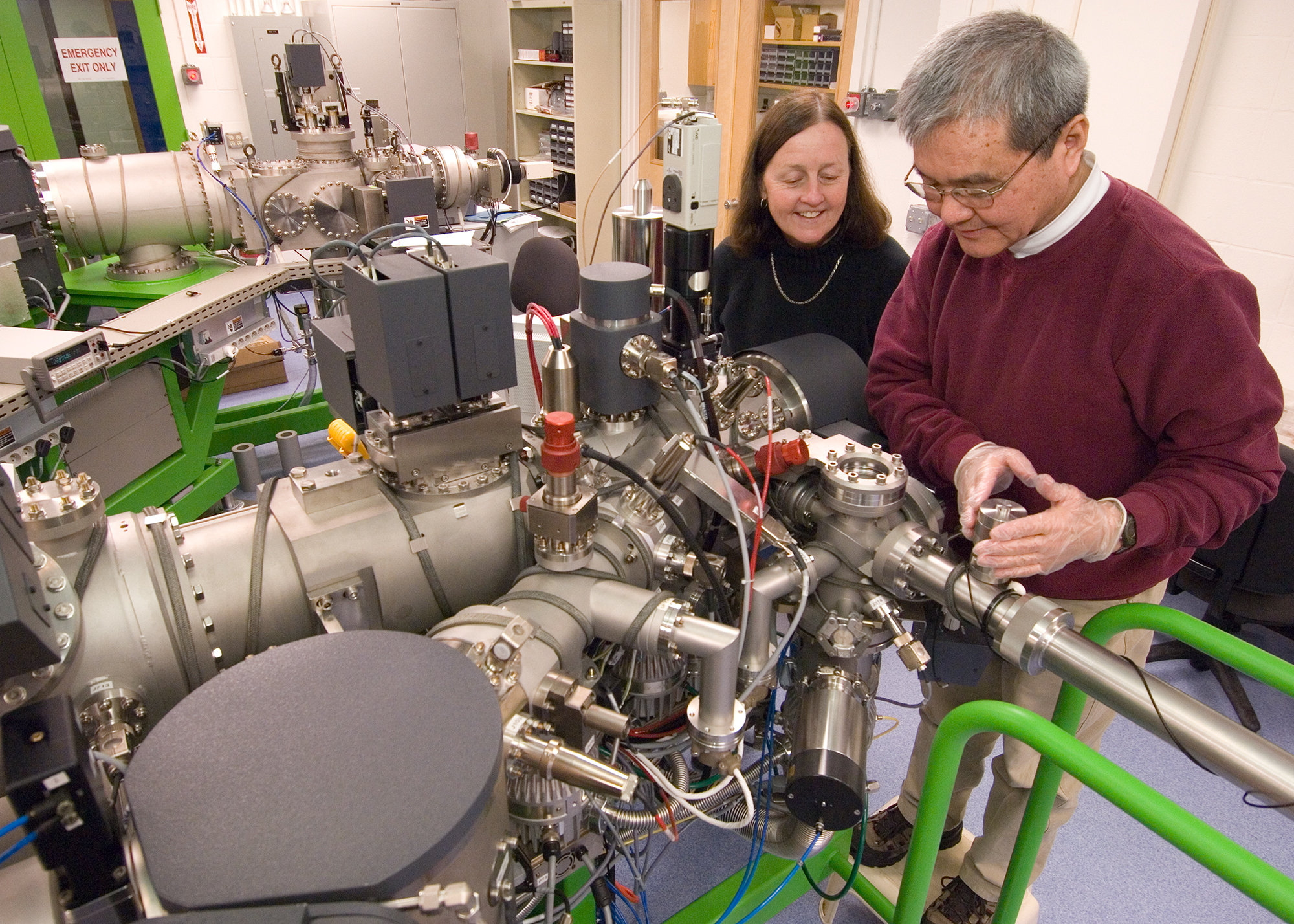

Susan’s first research cruise in 1973 on Scripps’ R/V Melville allowed her to develop the essential sea-going skills needed to advance her scientific career. “I would help with the coring, and then would also stand watches” for the echosounders as they poured out paper records. After the cruise, Susan began to explore dissertation topics. She attended a conference in Woods Hole where the indirect evidence for hydrothermal circulation at mid-ocean ridges was discussed. Her advisor, Geoff Thompson, pointed out samples in the WHOI rock collection that had been altered at high temperatures but had not yet been explored. “I decided to do a thesis on these altered rocks,…determine what reactions had taken place during their reaction with sea water and what elements were exchanged, and that way try to predict what the importance of hydrothermal circulation for the chemistry of the oceans might be.” Her findings were very timely as seafloor hydrothermal vents were discovered in 1977 – the same year she completed the Joint Program.

A few days after finishing her thesis, Susan Humphris packed up for her a new opportunity as a postdoc at Imperial College in London, believing this to be her avenue to a research and teaching career in Oceanography. However, the time was short- lived as opportunities in academia were minimal in the United Kingdom, budgets were limited, and time on research vessels was very restricted. An additional factor that drew Susan back across the pond, was her marriage to Pat Lohmann, a paleoceanographer, in 1978.

While spending a year at Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory in New York, Susan received a phone call from the Sea Education Association (SEA) in Woods Hole that gave her the chance to return to sea and teach students on board their sailing research vessel. This ultimately culminated in Susan being offered the position as a staff scientist for SEA and a return to Woods Hole.

The decade plus that Susan Humphris spent at SEA was not overly research- focused, but gave an amazing opportunity to teach young people (mostly undergraduates) about marine sciences and life at sea. For the first six years, her role as a Staff Scientist involved running semester-long courses, the first half of which involved “ daily lectures and two or three labs a week” on shore, and then continued at sea for six weeks. Her experiences helped craft Susan’ s approach to educating and mentoring young oceanographers:

I think as time went on, I started to realize that the whole idea of students actually participating in research was much more important than students sitting there listening to me talk at 8 o’clock every morning. I began to develop an appreciation for experiential learning, and I really think that the whole move towards experiential education is a very good one. SEA’s been doing it for a long time.

To keep her foot in research, Humphris remained connected to WHOI during her time at SEA through visiting appointments. Her former advisor, Geoff Thompson, gave her space in his lab. In 1985, she was made Dean and Senior Scientist at SEA, juggling her roles at both SEA and WHOI, and thinking about the next steps in her career. With the urge to return to scientific research, but acknowledging the need to build up her credentials, she took an opportunity to return to WHOI in a technical role. The office for RIDGE, a NSF program to study the mid-ocean ridges, was moving to WHOI for three years and needed a person to coordinate national research efforts for the program. In 1992, Susan returned to WHOI as a Research Specialist. “My plan was that I was going to use this as a bridge to get back onto the scientific staff. For the three years that I had this administrative job, I would try to build up my own science programs so that when this position rotated to its next venue, I would have enough science funded that I could stay at the Institution.”

WHOI Period

The possibility to rejoin the WHOI scientific staff was raised in 1997 by Bill Curry, then Chair of the Geology and Geophysics Department . With her experience, as unorthodox as it was in comparison to others, it was believed that she could qualify for a tenured associate scientist position. Humphris submitted her file and waited…and waited…and waited. Then during a visit to her parents in England, her mother answered a call “from someone named Bob Gagosian.” From the other end of the line came the news that Susan did not get the appointment as tenured associate scientist, but as a tenured senior scientist! The external letters of recommendation had glowing reviews of Humphris work and suggested that, through her research and leadership, she had already reached the expectations of a senior scientist.

Becoming a member of the tenured scientific staff did not mean that Susan’s work was done; rather, it opened up a new phase in her life in marine sciences. She continued working with the international Ocean Drilling Program, serving as co-Chief Scientist on two JOIDES Resolution cruises, and serving on many advisory panels over the years.

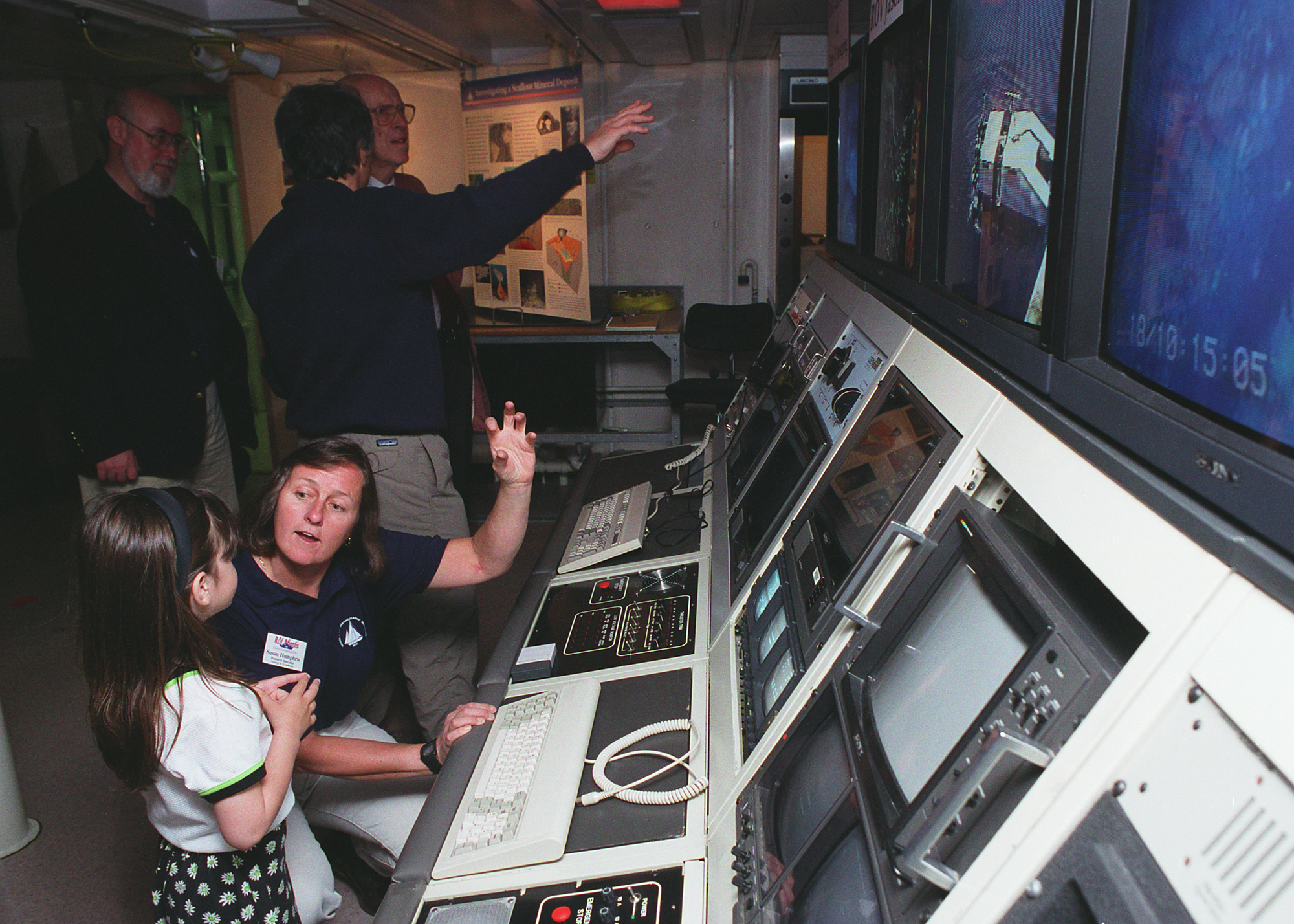

Seeing the experiential learning potential in research cruises, Susan, together with Dan Fornari, developed the Dive and Discover website in 1999. This allowed classrooms to have nearly real-time access to the research being conducted by WHOI scientists, vessels, and submersibles. Students were given the opportunity to interact directly with the researchers to learn more about the fields, work, and opportunities. “There’s a big opportunity out there being missed,” she told reporters, “not only to educate students but to make science very exciting.” In 2001 and 2002, the website was chosen by Scientific American as one of the internet’s best science and technology sites for Earth and the environment.

Throughout her time at WHOI, Susan Humphris has contributed over 100 publications relating to her work on hydrothermal vents and their geochemical characteristics . She has given her professional experience to many national and international scientific organizations or projects that have taken her to virtually every part of the ocean. Humphris has close to 2 years at sea on oceanographic vessels, made many dives in submersibles, and taken many students and K-12 teachers to sea. She has served WHOI as the Director of the Deep Ocean Exploration Institute, Chair of the Geology and Geophysics Department, and interim Vice President for both Research and Marine Operations at different times. Susan’s work on over 15 committees at WHOI involved her in selecting some of the most important projects and people for the Institution. Even though her status is now Emeritus, Susan Humphris still contributes to the Institution’s success as the Reopening Coordinator for WHOI COVID-19 protocols.

While her roles, committees, vessels, grad students and post docs all changed throughout Susan’s career, her commitment to education runs through all of it. Since she began her professional career in 1978, there has not been a single year that Susan has not been involved in education. The Massachusetts Marine Educators have bestowed honors on her twice and she held distinguished chair/lecturer positions four times over her career. Susan has contributed to national education programs as well. From 2000-2008, she worked on several steering committees for the NSF to increase literacy in geosciences, oceanography, and other scientific fields.

Through all of roles and experiences, Susan Humphris has been witness to another change in oceanography and marine sciences: the role of women. “It’s very clear that there are many more women coming into the field,” she said in an interview. “Half the graduate students are women now, which is great. I think conditions at sea have changed a lot. There’s often cruises where women outnumber men now. The attitude of the mariners has changed a lot, so I think going to sea has become much easier. I think the fact that there are more women at sea has also changed the tenor of the conversation at sea. And I think it’s improved.” Susan Humphris has been part of an amazing period in the contributions of women to science and oceanography. On her first cruise in the 1970s, some of the seamen wouldn’t speak to her. She worked, like many others, to create a field welcoming of women and their contributions, and oceanography is better because of her and others’ efforts. Susan set an example that with a plan one can make their goals reality, even if in a non-linear way, instead of waiting…and waiting…and waiting….