Roberta Eike: The stowaway who made waves for women scientists today

By Brett Freiburger

Please note: The following includes descriptions of sexual abuse which some readers may find troubling. Discretion is advised.

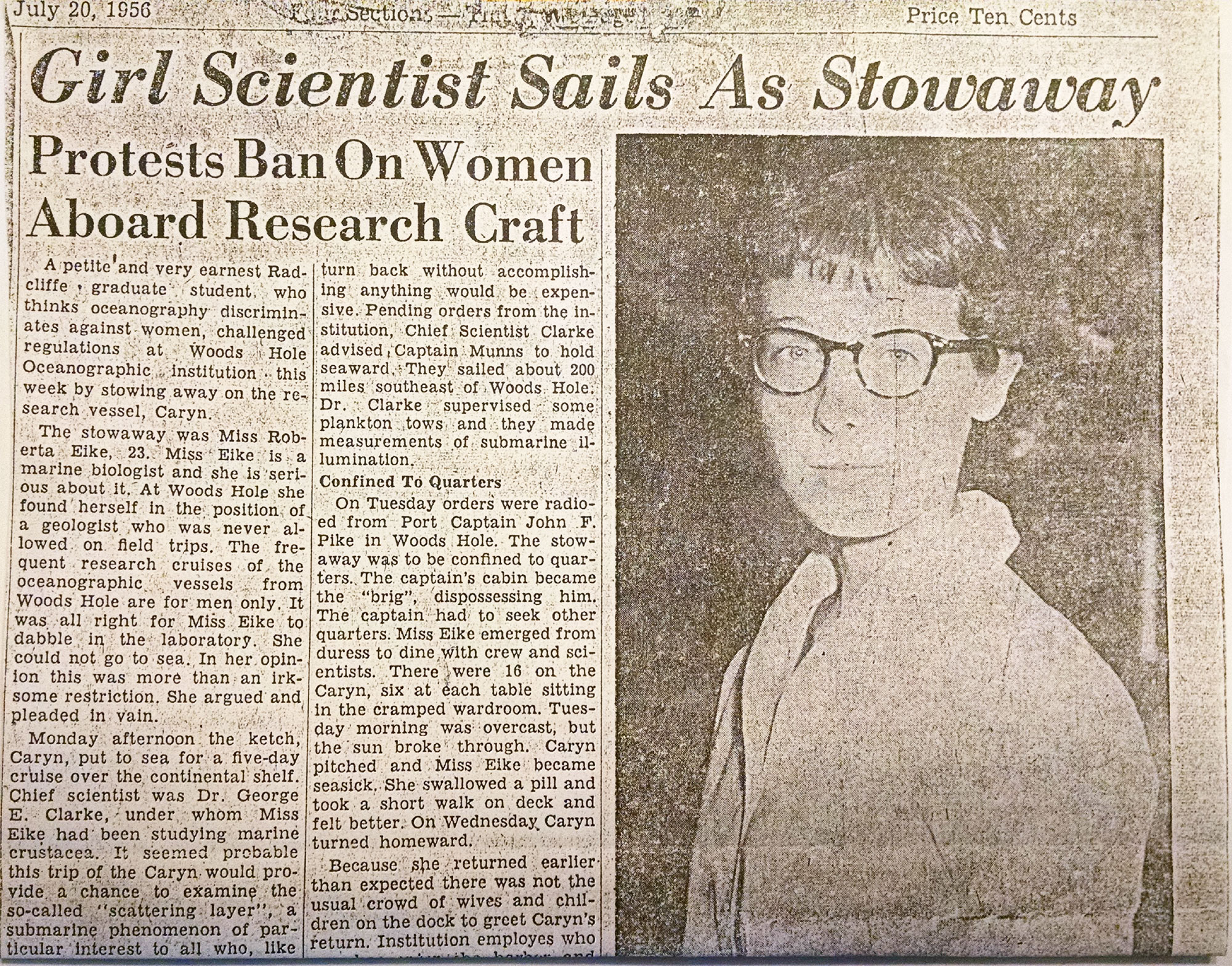

Surely, one couldn’t be an oceanographer without going to sea? But that wasn’t the case for women in the 1950s. In 1954, an earnest biology graduate student named Roberta Eike became aware of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) while on scholarship with the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. She became a Radcliffe student and took a chance to work with George Clarke, a life-long WHOI authority on marine ecology and pioneer in instrumentation. In her second summer, after appealing to R. Adm. Edward Smith, Alfred Redfield, and Clarke to conduct her necessary research at sea, Eike was denied access to the sea again and again. Unable to research at sea, Eike felt the future of her research, Fellowship, and career were at risk. So, on July 16, 1956, she took a chance.

On what seemed a routine morning, Roberta Eike gathered “oranges, peaches, cookies, a change of socks and clothing, a green cloth bag with jars to collect plankton” and boarded CARYN, taking up quarters in the bilge with the engine and extra stores. After several hours, and rolling seas Roberta left her hiding spot and emerged – sick- where she was found by the captain, Bob Munns.

With a mix of shock and awe, Munns steered and did a literal 180-degree turn with CARYN. In the dead of night, the ship’s course-corrected in a flash. The CARYN’s new bearing, 197 to 017 at 0020 hours, was made just five minutes after Eike was discovered. Perturbed by the long-held, out-dated “no women at sea” rule, George Clarke, her advisor, and Chief Scientist had Munn continued with the research voyage. Eike was confined to the captain’s quarters.

Feeling bound to tradition, Adm Smith pushed the CARYN back to dock by July 18. Back and shore and punished for her dedication, Eike was stripped of her Fellowship title, a move which ultimately led to her quiet departure from the institution.*

Her dismissal sparked much debate and was a catalyst for igniting the conversation about women at sea on WHOI vessels. Some of the biggest names in oceanography defended her: Alfred Woodcock, Dean Bumpus, Valentine Worthington, Joanne and William Malkus, William von Arx, Henry Stommel, and Dick Backus.

Backus knew of Eike’s plans and did attempt to dissuade her. Backus, a friend, and mentor would later recount, “Her gutsy act turned the attention of the WHOI community to the issues of women at sea as it had never before. Consider the problem: one couldn’t be an oceanographer without going to sea. Did that mean that women couldn’t become oceanographers? The answer was the one that a trifling amount of thought had given in all such cases: it not only would be unfair, but it would also halve the pool of talent. Further, so long as oceanographic research was mainly paid for with public funds, the prohibition of women on research vessels was surely doomed. It would be dishonest were I to leave the impression that I was always a champion for women’s participation. I enjoyed purely fraternal sea-going along with the rest, but when the argument was finally joined I accepted the inevitable and soon found life at sea with women a little different, but no less enjoyable.”

Pressured by a swell of voices, six years after Eike stowed away on the CARYN, women officially joined WHOI sea-going research vessels. Over 40 years later WHOI has come a long way. Since Eike’s courageous decision, women have occupied major positions across the institution, piloting the submersible ALVIN, leading as Chief Scientists, and in one case becoming WHOI’s first woman president. In addition, the WHOI Women’s Committee is actively engaging the WHOI community to continue the dialogue towards continuous improvement initiatives so all women are treated equally and respectfully at shore or at sea.