Elizabeth “Betty” Bunce

By Brett Freiburger

“She had fashioned a remarkable career out of the oddest assortment of parts: athletic prowess, an atomic bomb, a Smith firing, nosiness, and smidgen of luck.”

-Kim Robert Nilsen, “Oceans, Atoms and Earthly Secrets

Elizabeth Thompson Bunce was born April 25, 1915, in Mineola, New York; a Long Island town that became world-renowned when Charles Lindbergh departed from Mineola to begin his historic flight across the Atlantic. During the Great Depression, Bunce attended Northfield School for Girls, graduating in 1933, but not before showing her inquisitive nature. Betty and a friend decided to find there way into the abandoned and daunting Chateau. “We found an open cellar window,” said Bunce, “and we snuck ourselves in, into the coal bin…We came out behind the fireplace in the big hall with all the mirrors.” As the girls explored the long empty building, they found their way to the kitchen and saw evidence of a meal in progress: fresh sardines and a box of crackers. “I’ll tell you something: you have never seen two people leave a place so fast.”

Elizabeth Thompson Bunce was born April 25, 1915, in Mineola, New York; a Long Island town that became world-renowned when Charles Lindbergh departed from Mineola to begin his historic flight across the Atlantic. During the Great Depression, Bunce attended Northfield School for Girls, graduating in 1933, but not before showing her inquisitive nature. Betty and a friend decided to find there way into the abandoned and daunting Chateau. “We found an open cellar window,” said Bunce, “and we snuck ourselves in, into the coal bin…We came out behind the fireplace in the big hall with all the mirrors.” As the girls explored the long empty building, they found their way to the kitchen and saw evidence of a meal in progress: fresh sardines and a box of crackers. “I’ll tell you something: you have never seen two people leave a place so fast.”

Bunce honed her spirit of investigation at Smith College where she learned all she could about government, politics, history, and economics while competing in soccer, lacrosse, and field hockey. She graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in 1937 – entering the workforce with America still in the throes of the Great Depression. Betty quickly realized she needed something more long-term than tutoring and turned to her love of sports. She returned to Smith in 1939 to pursue a graduate degree in physical education, earning a Master’s degree a few months before the U.S. entered World War II. During the early days of the War, Betty found a job in New Jersey as a physical education teacher for the Kent Place School, where she also led the field hockey and lacrosse teams (Bunce herself was All-American Reserve Team member in both). During this time, Betty also served as an air-raid warden, a WAVES physical instructor, and took the armed-forces advanced-rating courses. It was these courses and a chance vacation to Woods Hole, MA that sparked the historic relationship between Betty Bunce and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

While visiting a friend for the summer in Woods Hole, Betty stumbled upon the opportunity to “take the pulse of bombs.” The project Bunce joined, Navy 7, dealt with the study of various types of high-explosives detonated in the air. Betty worked on the contract for John Bracket Hersey, where she “recorded the shock waves, measured the peak pressure and the impulse” photographically with the goal of “trying to find out where one fused the bombs to detonate – at what altitude – so they would do the most damage.” This information was used not only for combat, but also in the Manhattan Project. When the first atomic bomb was dropped on Japan, the news was shared with the team at WHOI. When news reached the team at WHOI of the atomic bomb, they knew exactly the important scientific advancement it represented – nuclear fission. Amid this, Betty, not fully understanding the importance of this advancement, decided “very simply, right then and there, that I had egg on my face. I hadn’t the slightest idea what this was all about. But I had to find out. I had to!” She returned again to Smith for another graduate degree, this time in physics and math.

While visiting a friend for the summer in Woods Hole, Betty stumbled upon the opportunity to “take the pulse of bombs.” The project Bunce joined, Navy 7, dealt with the study of various types of high-explosives detonated in the air. Betty worked on the contract for John Bracket Hersey, where she “recorded the shock waves, measured the peak pressure and the impulse” photographically with the goal of “trying to find out where one fused the bombs to detonate – at what altitude – so they would do the most damage.” This information was used not only for combat, but also in the Manhattan Project. When the first atomic bomb was dropped on Japan, the news was shared with the team at WHOI. When news reached the team at WHOI of the atomic bomb, they knew exactly the important scientific advancement it represented – nuclear fission. Amid this, Betty, not fully understanding the importance of this advancement, decided “very simply, right then and there, that I had egg on my face. I hadn’t the slightest idea what this was all about. But I had to find out. I had to!” She returned again to Smith for another graduate degree, this time in physics and math.

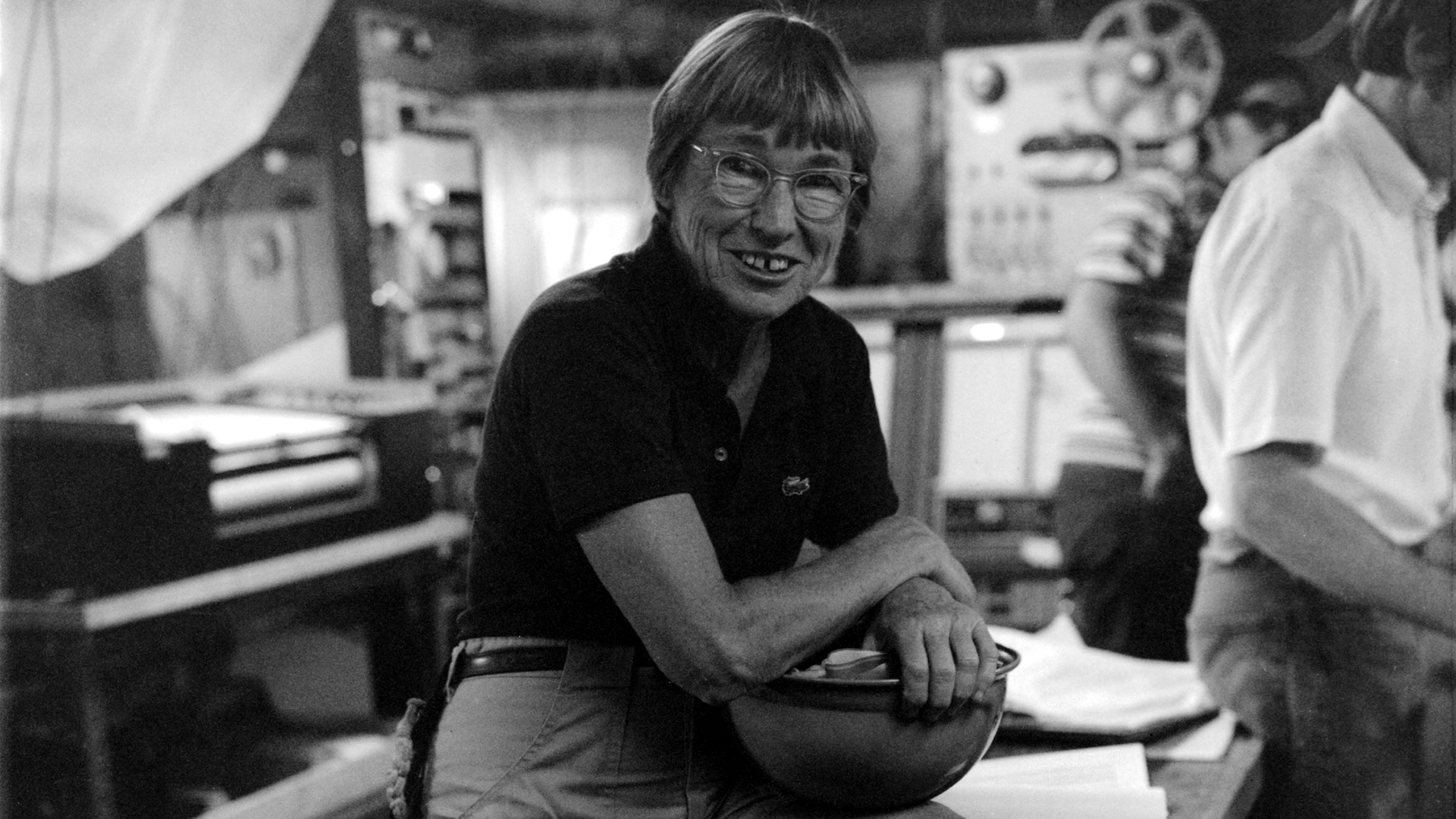

“I never spent a tougher year in my life,” Betty later recounted. Her determination paid off as by 1951 she had completed her Master’s, taught physics at Smith (she was even in line for a promotion to assistant professor) and continued her summer work at WHOI. However, policy changes at Smith eliminated her position and this fortuitous lay-off cemented her future at WHOI. She learned of a more permanent position under J. Brackett Hersey, wrote to him expressing interest and convinced him to bump the pay up from $300 to $330 a month. In July 1951 Betty moved to the Cape. A year later, Bunce was still convinced that the move was temporary, but her promotion to Research Associate in Physics made it possible for her to blaze a trail for fellow women scientists.

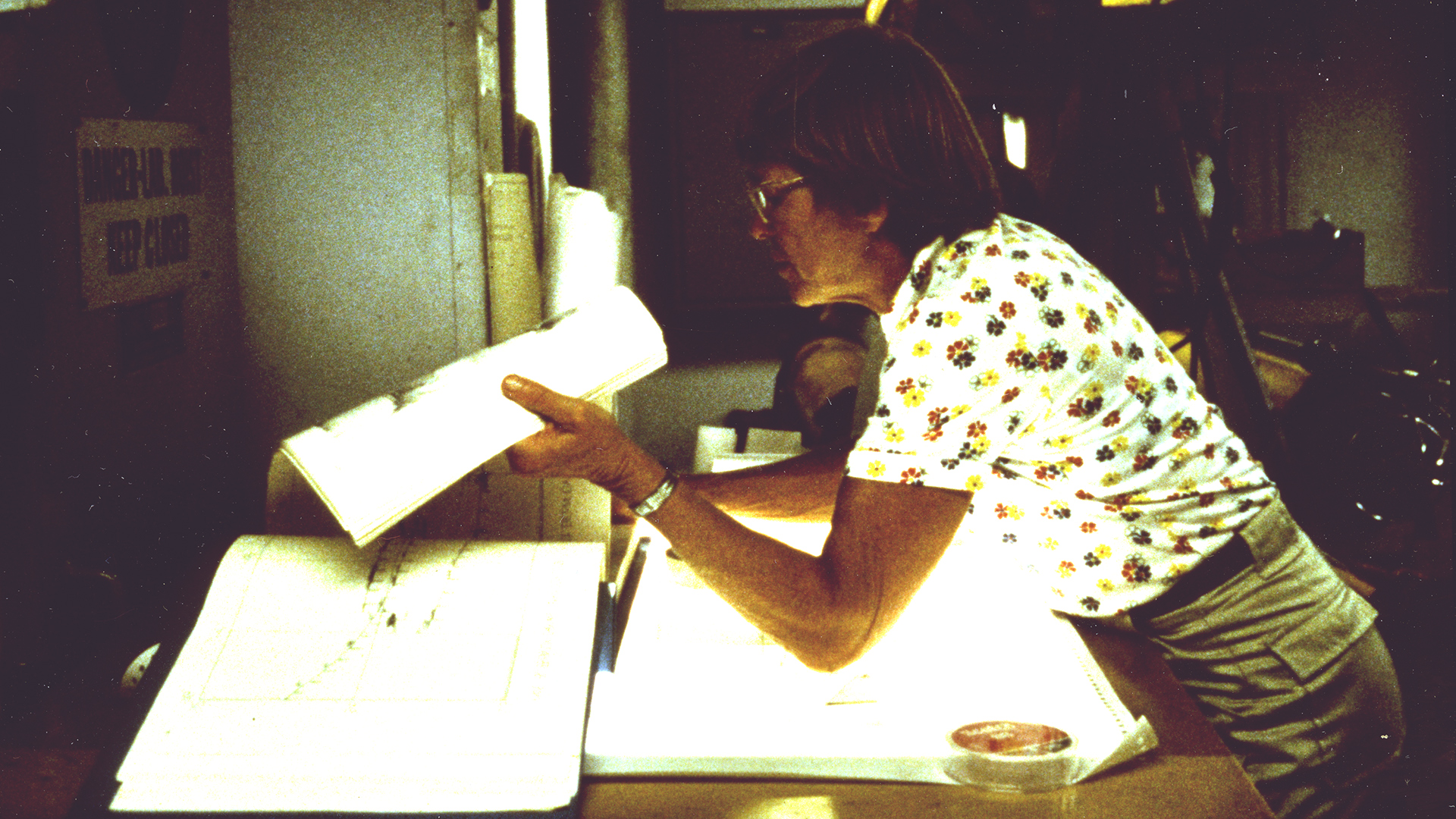

Betty Bunce may not have had the most glamorous or groundbreaking studies at first, but that changed over her first decade at WHOI. She began with testing underwater acoustic instruments moored “in a quiet Cape Cod pond,” before being placed in charge of the day trip studies aboard the Bear. In 1956, Betty began carrying out seismic studies of Narragansett Bay for the Corps. of Engineers on a two-year study. These early accomplishments built her credibility as a female scientist amongst the male-dominated field and research staff at WHOI; her tenacity, intellect, and curiosity demonstrated her commitment and skills. In 1959 a research cruise aboard the Bear guaranteed Bunce a place in history; she was the first American female Chief Scientist for a major oceanographic expedition. Her research during this time allowed her to present a paper at the International Union of Geology and Geophysics as the first western woman to lecture on Marine Geophysics. She even appeared on the popular television show To Tell the Truth and fooled three of the four panelists!

Betty served as Chief Scientist on many WHOI cruises throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In 1964 she was promoted to Associate Scientist and served as Chief Scientist on a major phase of the International Indian Ocean Expedition to map that region’s seafloor. The next year she was the first woman to dive in Alvin, WHOI’s famous submersible. Bunce returned to the Indian Ocean in 1971 to conduct site surveys that laid the groundwork for drilling by the Joint Oceanographic Institutions for Deep Earth Sampling (JOIDES). The Indian Ocean is also where Betty Bunce set another first as the first woman to share Chief Scientist on the Glomar Challenger, a vessel that drilled samples to help prove the theory of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics. It was during one of these cruises that Bunce sent her oft-used punching bag overboard during a workout and demanded the ship turn to retrieve it! Her research during this time involved the five-mile Puerto Rican Trench; shortly before Betty passed away a significant fault line between the North American and Caribbean plates in the Trench was named in honor of her pioneering work.

In 1971, Smith College recognized the strides that Betty Bunce made for women in oceanography. At the 93rd commencement of Smith College, Bunce was awarded an honorary doctoral degree in science. Her appointment as a WHOI Senior Scientist in 1975 was more than well-earned and her accomplishments were further acknowledged when she became the first woman to serve as an interim department chair. WHOI turned to Betty multiple times over the 70s and 80s to oversee the Geology and Geophysics Department during transitional periods. After thirty years at Woods Hole, Bunce decided to retire in 1980 and was honored once more with an appointment of Scientist Emeritus. By the time Betty Bunce retired her research had covered crustal structure, marine seismology, reflection and refraction, and underwater acoustics associated with seafloor studies; she was the author or co-author of more than 25 papers in marine geophysics; she had blazed a trail for female oceanographers; served on professional and institutional committees; and she still had work to do.

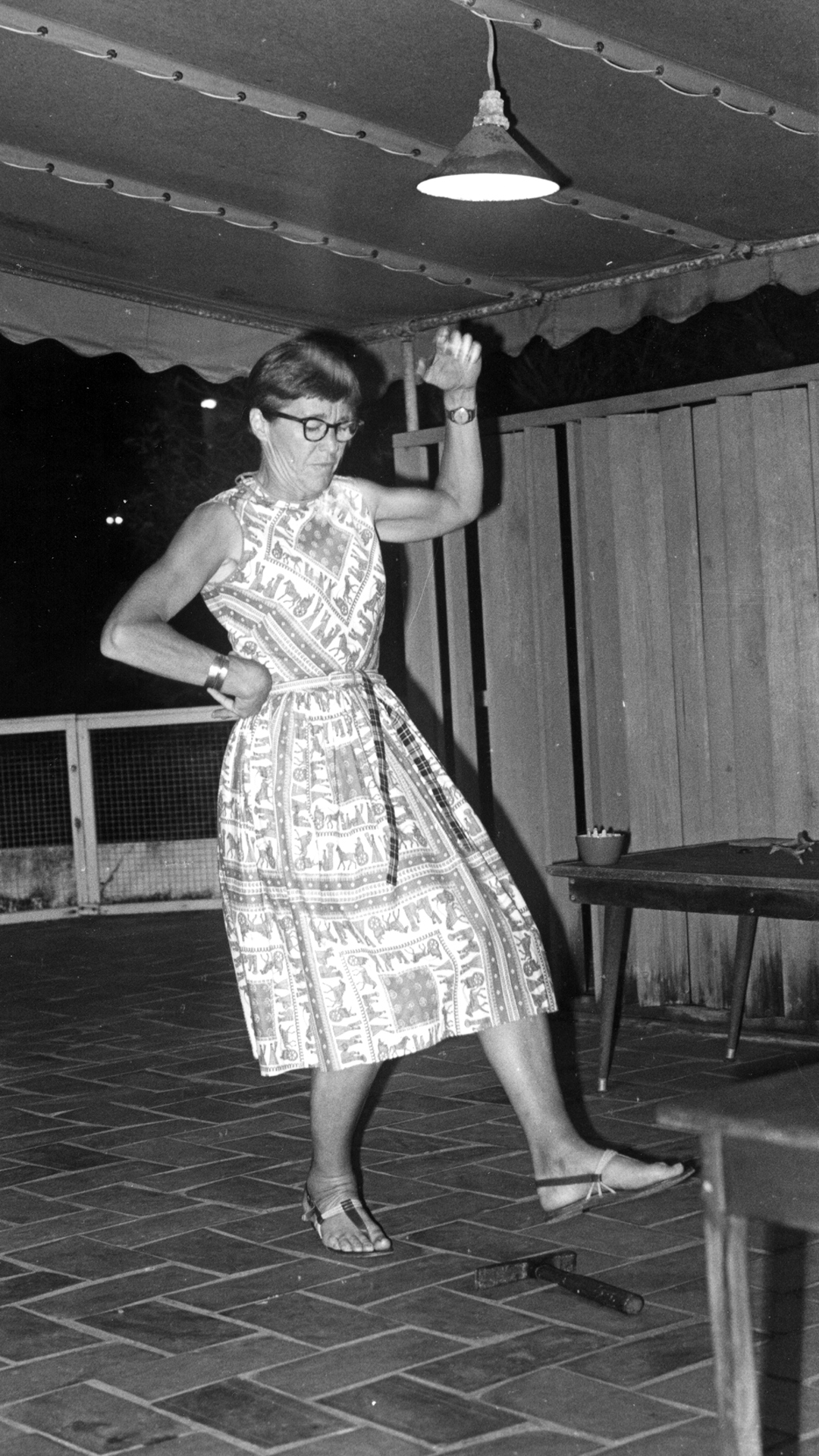

Following retirement from WHOI, Betty turned her tenacious spirit towards helping the Falmouth community. She volunteered at Falmouth Hospital for many years and worked the desk and stacks for the West Falmouth Library. Bunce continued her love of nature and physical activity in her emeritus days. She could be spotted on the trails, bird watching, or rowing around the waters of Woods Hole. At age 74 she even set a world record for her age group for the 2500 meter in indoor rowing!

Following retirement from WHOI, Betty turned her tenacious spirit towards helping the Falmouth community. She volunteered at Falmouth Hospital for many years and worked the desk and stacks for the West Falmouth Library. Bunce continued her love of nature and physical activity in her emeritus days. She could be spotted on the trails, bird watching, or rowing around the waters of Woods Hole. At age 74 she even set a world record for her age group for the 2500 meter in indoor rowing!

In March 1995 she was honored at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s second “Woman Pioneers in Oceanography” seminar, during which her friends and colleagues recounted some of her many contributions to oceanography. Long-time colleague John Ewing described Betty Bunce as:

…a total marine seismologist who contributed much to the field in the early days. She could get on the back deck with the guys, she could record, and she could interpret. She was very dedicated – a good solid customer and a pleasure to know. She made her presence felt daily because she doesn’t mind jacking anyone up. But she was quite highly respected. She earned it.

Along with the Pioneer Award, Director Robert Gagosian announced that Betty would be co-commissioner for the new research vessel Atlantis.

“The saddest day in my life,” Bunce once said, “was when I was very young and I was told I was a girl and there were things that boys could do which girls couldn’t. That meant I couldn’t be a sailor.” The dogged determination that Betty Bunce had to overcome being born a woman in a world with very defined gender roles is reflected in the her legacy. A legacy that changed the field of oceanography; opened doors for women in science; and showed everyone how to realize their full potential, to make material their dreams, and to never let anything get in the way of being their true selves.