Cindy Van Dover “Just by asking, I could live my dream”

By Brett Freiburger and edited by the WHOI Women’s Committee

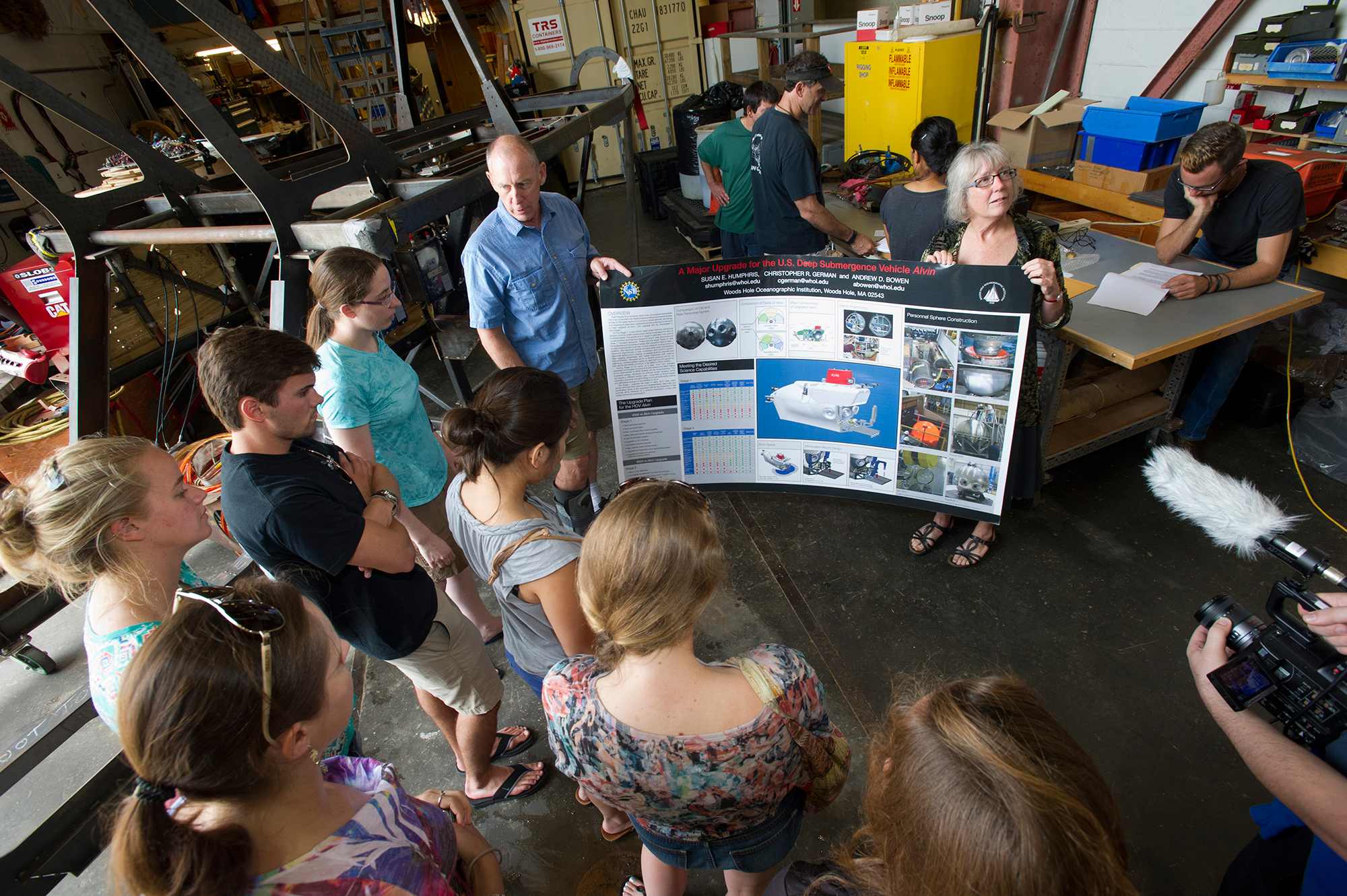

Women at WHOI fought an uphill battle towards equality—in the lab and at sea. As the US went through the massive cultural changes in the twentieth century, WHOI opened their ships to female researchers. The number of women at WHOI began to increase in the sixties, and is still growing to this day. One of the last sectors to admit women at WHOI was one of its best-known: the manned submersible DSV Alvin. In 1971 Ruth Turner was the first female scientist allowed to dive in Alvin, but there would not be a female pilot until nearly twenty years later when biological oceanographer Cindy Van Dover decided that being a pilot was “the only way to see the seafloor. Nobody gets a better view than the pilot.”

Cindy Van Dover grew up in New Jersey and spent every summer day at the beach. “That’s where I discovered those strange, crazy invertebrates,” she later recalled. Those explorations led her to attend Rutgers University (as a member of its first co-ed class) to study Environmental Science. One semester she landed a student position at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, working on clam and oyster biology. Van Dover “felt like I had landed where I belong.”

Van Dover completed her Bachelor’s degree at Rutgers in 1977, then she applied to the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Biological Oceanography, but was not accepted. Instead she went south to Duke University Marine Lab. As a technician at Duke she worked on a variety of projects with Dr. Bill Kirby-Smith, including the writing and publication of A Field Guide to Common Marine Invertebrates of Beaufort, North Carolina; which is still in use today. “Cindy has always liked to do something different,” commented Kirby-Smith, her residence in a tent and commute by canoe are just two examples. Van Dover’s wanderlust took her to new ventures and in 1979, she left Duke.

For the next few years, Cindy traveled up and down the East Coast, working as a technician in various labs and following her boyfriend to Cornell where she “hung out and read marine ecology papers.” One of those papers discussed the discovery of hydrothermal vents and its shockingly thriving ecosystems. She was fascinated. This “Garden of Eden” at the bottom of the sea “showed me how extreme life on Earth could be.” A chance letter to Austin Williams, the biologist who first described hydrothermal vent ecology, resulted in Williams sending Van Dover samples to study on her own. Her work on these became her first publication.

The “celebrities” of the hydrothermal community met in Washington DC in 1982 to discuss the rapidly developing field focused on these newly-discovered ecosystems. At the meeting Cindy Van Dover learned of an upcoming study on the East Pacific Rise as part of the OASIS project, and approached the researchers leading the trip and to ask if she could join the team. Their response was an emphatic “Sure!” and off she went on her next adventure. “It was amazing,” she later recalled, “just by asking, I could live my dream.” After these exciting opportunities and accomplishments, Van Dover reapplied and was again rejected from the MIT/WHOI Joint doctoral Program.

Undeterred by her second rejection, Cindy Van Dover enrolled in a master’s degree at UCLA with a focus on mathematics and theoretical ecology. In 1985, Cindy had her MS degree and her first opportunity to see the seafloor firsthand. She joined an expedition to the Rose Garden hydrothermal vents near the Galapagos archipelago expecting to serve in a similar capacity as the OASIS cruise – as a research assistant. One night however, after looking over the Alvin dive plans for the next day, Cindy saw her name. “I couldn’t sleep,” Van Dover recalled. She spent most of the night on deck, peering over the side and imagining the splendor of the seafloor thousands of feet down. Seeing it firsthand forever changed the way she viewed the world.

When the cruise returned, Van Dover received an offer from one of the expedition’s scientists, Carl Berg, to work with him at WHOI. Here she analyzed some of the first hydrothermal vent plankton samples. WHOI’s Fred Grassle encouraged her apply to the MIT/WHOI Joint Program once more. On this third try Van Dover was accepted and began her PhD program in 1986. Within three years, a remarkably short period, Van Dover completed her doctorate in Biological Oceanography. Her PhD culminated in important work on how shrimp at hydrothermal vents use their “eyes” as infrared sensors to avoid the high temperatures of the direct venting, or as Cindy liked to say, “getting cooked in the chimney stack”. On her first cruise as Dr. Van Dover, she dove again in Alvin. During this and many previous dives, she noticed that the submarine pilots visit the seafloor frequently, and that they have the best views.

An opportunity arose when Van Dover was helping the Alvin engineers draft a manual for the required routine maintenance. With all of the materials at her finger tips, support from the Alvin team, and the knowledge that being a pilot would give her more time on the seafloor, Van Dover began the intensive nine-month program to become an Alvin pilot. Months of training included memorizing how to operate all the check valves, autoclaves, ballast systems, oxygen monitors, electrical systems, and all the safety measures required to operate the submersible. “It was like going back to kindergarten. My brain cells ached at the end of the day,” she recalled. The final exam entailed multiple oral and written exams over three days, ending with a solo dive in Alvin. In 1990, Cindy Van Dover was pinned with the Navy’s Dolphinfish pin and became the 49th certified pilot of DSV Alvin. Her first dive with researchers Elana Leithold and Cynthia Huggett aboard was the first time that Alvin had been operated and staffed with women. Today she still holds the title of the only female Alvin pilot.

While the Alvin pilot position gave Cindy greater access to the deep sea than any other scientist before her, she decided to transition back to research after piloting 48 dives in Alvin over two years. She began a post-doctoral project in the Marine Chemistry & Geochemistry department at WHOI, and continued as a visiting investigator in the Geology & Geophysics Department from 1995-1998. In 1996 Van Dover published a memoir about her explorations of the hydrothermal vents, The Octopus’s Garden. At the same time she wrote The Ecology of Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents, the first textbook on the ecology of the hydrothermal vents that she had spent decades researching. Beginning in 2004, the Van Dover lab undertook baseline studies for Nautilus Minerals, a Canadian mining company, to inform environmental management of deep-sea mining. Van Dover is now contributing to efforts to ensure that effective conservation practices are in place before mining begins on the international seabed. She taught courses and led research in the deep sea at The University of Oregon, The University of Alaska, The College of William & Mary, Duke University, and returned to Duke University in 2006 as the first female director of the Duke Marine Laboratory and the first director to hold this title for two consecutive terms. From 2008 until the present she has served as Harvey W. Smith Distinguished Professor of Biological Oceanography in the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University.

Cindy Van Dover is an exemplar of setting a goal and reaching it on their own terms. She is an inspiration to women everywhere that if they want to live their dream, they just need to ask the right questions – of themselves, the profession, and the world.