Students off to sea; 20 students, 30 hours at sea: A headfirst dive into fieldwork.

Written By: Eeshan Bhatt, Jacob Forsyth, and Joleen Heiderich

The JP’ers gather round to organize themselves. Photo: Eeshan Bhatt

Months of planning all converged on 30 hours at sea aboard the new WHOI-operated research vessel, R/V Neil Armstrong. For not a lot of time at sea, we had quite a bit to do and a lot to learn.

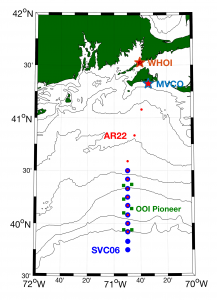

The cruise track.

This Long Term Ecological Research track is aimed at supplementing the Pioneer Array data with more chemical and biological data but from shipboard measurements instead of equipment that stays in the water. The combination of the Pioneer Array and Long Term Ecological Research site will allow scientist to observe changes in this area from year to year, and over longer time spans.

Our goals on this cruise were two-fold: to collect hydrographic (physical data like temperature and salinity) and biological (phytoplankton species and abundance) data in the region, and to educate the incoming class of Joint Program graduate students on the different techniques used to collect data at sea and what life at sea is like.

These suits are no joke. The bright orange makes you visible in a blue-green horizon. Photos: Joleen Heiderich

At 0730 Saturday morning, the science party was assembled to get safety trained before watches started. One of the most important things for us to know was where to go and what to do in case we were told to abandon ship. This required us to learn how to put on bright red survival suits (see photo below).

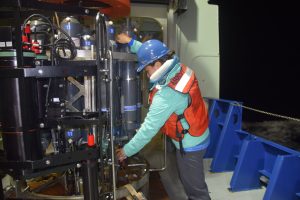

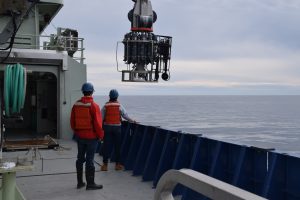

The first watch began at 1400 (2 pm) and went until 2000 (8pm). We established our sampling stations on a course aimed south out over the shelf and at each station we deployed a collection of CTD (conductivity, temperature and depth) instruments, as called a CTD rosette. The CTD rosette is lowered over the side of the ship, and records conductivity (which gives us salinity), temperature, pressure (which gives us the depth), dissolved oxygen, and other properties of the water. Through a fiber-optic cable connected to the CTD, we are able to see this data in real time, and then, as the

CTD is raised back up, we could decide where to collect watersamples in the Niskin bottles attached to the rosette frame. A Niskin bottle, is essentially a long, hollow tube that can be closed at a specific depth in order to capture water from that layer of the ocean and bring it up to the surface without it coming into contact with other water. Once back on board, we can collect smaller sub-samples of water from each bottle for further analysis that can only be performed in the ship’s lab or on land.

Preparing instruments. Photo: Eeshan Bhatt.

We also attached a new Video Plankton Recorder (VPR) to the CTD frame, which takes pictures as it moves through the water. A software program developed for the VPR is able to identify the plankton in the pictures, typically at the family/genus level. In addition, we used the ship’s wide-band echo sounder to look at the backscattering of the water column. Air bubbles, fish, phytoplankton, suspended sediment, internal waves, and even drastic changes in salinity scatter different amounts of the acoustic energy sent out from the echo sounders on the bottom of the ship’s hull that can help us identify what is in the water beneath us and how deep it might be. Our next step was to use the trawl winch to pull a ring net from a chosen depth to sample those organisms.

A CTD rosette ready to be deployed. Photo: Eeshan Bhatt.

Near the end of the first watch, we found out that the trawl winch, which was working during the land test, malfunctioned – we were being taught first hand that you have to be prepared for anything while at sea. After a quick science meeting to discuss what we would do with the time we had planned for the net tows, we looked at the data we had already collected and decided to add two stations perpendicular to the line connecting our first 10 stations, which allowed us to gain a three-dimensional view of the area. For the students who were new to at-sea science, this was their first (but almost certainly not their last) lesson in how to remain flexible when something goes wrong and to make the best of rare and expensive ship time.

Kevin prepares a sample. Photo: Eeshan Bhatt.

While the first group of students were on watch, the second watch was trying to get some rest in their berths (beds), or watching TV in the lounge. The science party staterooms (bedrooms) are mostly double rooms with bunk beds, a bookshelf, a desk, some storage space, and a sink. If you’re lucky, you get a porthole (window) giving you a view of the outside. Each stateroom shares a head (shower and toilet) with the stateroom next door. Handrails become a must while showering in 8 foot waves! WHOI has a wonderful interactive panoramic photo of the stateroom here.

The sea was calm as the first watch began, but the waves grew until they were splashing over the side of the ship while the students worked on deck. Calmer seas are great at lulling you to sleep, but as the waves pick up, you can get jostled awake by the rolling.

Meal time, a chance to break and refuel. Photo: Eeshan Bhatt.

When you’re not working or sleeping, you’re most likely eating. The chefs do an excellent job keeping the science party and crew well-fed. Breakfast is offered at 0730, lunch at 1130, and dinner at 1700; R/V Neil Armstrong also offers fancy cheeses and breads at 1430, affectionately known as “cheese-thirty”, a tradition that the crew has carried over from the previous WHOI ship R/V Knorr. If you are on watch (or sleeping) during a meal, you can always grab leftovers from the fridge or help yourself to the ample amount of snacks available. Coffee is constantly available and brewed fresh around the-clock. On board, we aim to be as sustainable as possible. Everyone is assigned a mug for the duration of the cruise to clean themselves, food products are composted, and trash is either incinerated or saved to discard back on land

We could not have had a successful cruise without the R/V Neil Armstrong crew. At the end of the cruise, we sampled at 12 stations and steamed over 230 miles. They helped us navigate safely, answered all of our questions about doing science at sea safely, and stayed up with us throughout the night as we operated the instruments onboard.

We would like to thank the WHOI Access to Sea Grant for sponsoring this unique educational opportunity.

Time for the incoming class find their land/lab legs again. Photo: Glen Gawarkiewicz