Realize That You’ve Gotten Better

Written by: Suzanna Clark

In my first year of graduate school, my advisor told me, “It doesn’t get easier, you just get better.”

After a quick google search, I realized that this quote is not original. There are countless blog posts and inspirational pictures centered around it, usually in the context of either long-distance running or bicycling. Apparently, when bicyclist Greg LeMond said the original quote, “It doesn’t get any easier, you just get faster,” he meant that bicycling up a hill is always hard, regardless of how good you are. Clearly, in this context, the quote reads a bit more cynical. I’d like to turn it around.

It’s hard to look back and see how far you’ve come, especially when what you’re doing never seems to get easier. I see it in my classmates all the time: the frustration when an experiment doesn’t work, the struggle to remain motivated when you feel like you’re moving any direction but forward. I struggle with it myself, and usually it takes another person to remind me that a year ago I couldn’t do 90% of the things I’m doing today. But I think assessing your progress is a critical step in not getting discouraged. This is true in any context, but particularly in graduate school, where progress is so difficult to measure.

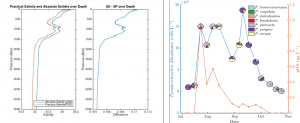

I’m currently in the (hopefully) final year of my PhD, and I’ve been reflecting lately on how much I’ve learned in the past four and a half years. When I started graduate school, I struggled to make simple graphs of temperature and salinity. I spent a whole week during my first winter term trying to load my own data into Matlab. Then in my third year I started learning how to run oceanographic models, which solve simplified physical equations to predict ocean currents, temperature, and salinity. Two years ago I struggled with downloading the model code, a year ago I was trying to get my model to run, and a month ago I couldn’t figure out why a simple run had an unexpected error.

Left: A figure from my second Problem Set in my first graduate school class. Clearly, I also didn’t know how to save figures at high resolution. Right: For comparison, a figure from my first paper.

Looking back on my journey, I could choose to interpret it two different ways. The first is to dwell on my two-year struggle to run oceanographic models. The second is to recognize that I’ve grown from not knowing what “running a model” meant, to not knowing how to run it, to editing the code itself so that the runs are more accurate. Both perspectives are true, but all too often I find myself stuck in the first mode of thinking, rather than appreciating the second.

This mindset is exactly what my opening quote means to me: the task doesn’t change, but I can get better at doing it. Odds are, the software, machine, or analysis technique you’re working with hasn’t changed much in the time since you started using it. If it seems easier now, you’ve just gotten better at using it. This applies to all aspects of life: studying in graduate school, starting a new job, trying a new sport, learning a new language, or even practicing better self-care. We get better by doing the thing, and we stay motivated by appreciating our progress.

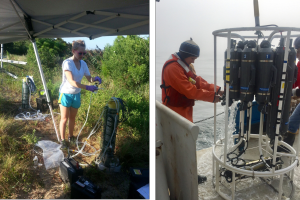

Left: Collecting samples from groundwater wells in Duck, NC in August 2016. Photo credit: Rachel Housego. Right: Prepping an instrument in a much different environment, the Gulf of Maine, in June 2019. Photo Credit: Maura Thomas

My opening quote is often used as inspiration for marathon runners, and I happen to have run a marathon. The nice thing about training is it’s easy to track your improvement: “This week I ran fifteen miles! Next week I’ll run eighteen!” Working toward my PhD feels like a marathon in its own right, but unfortunately there’s no online training guide that I can download to make sure I’m on track. There’s no daily plan that tells grad students exactly what to do next week, and next month, to move closer to their PhD.

Instead, I suggest tracking what you’ve already done. Think back to a year ago: what can you do today, or what do you understand today, that you didn’t then? If a year feels too long, do the same exercise with the past semester. Or the past month. Or yesterday.

For me, tracking my progress means keeping a notebook where I write down what I accomplished each day and its significance. This was a tip from an older student in my program that I find very helpful, because it not only reinforces what I’ve accomplished, but helps me to set reasonable expectations for the next day. I also like to take a step back every few months (I’m a “seasons” sort of person), reassess my goals, and outline new goals for the next few months. I write everything down, because looking back on my previous to-do lists helps me to appreciate how far I’ve come.

Your strategy might look different. A quick online search of “PhD track your progress” reveals that students all over the world struggle with this problem. An article by Bart Noordam and Patricia Gosling on sciencemag.org recommends evaluating your progress monthly, including assessing what goals you met that month, analyzing what went right and what went wrong, and setting actionable goals for the next month. It could also be helpful to talk to your classmates regularly to get their perspective and hear their feedback. It might take a few tries to find something that works for you. Finding your learning process is also a learning process… maybe I’ve been sitting at home too long and have become a bit too meta.

The point is to remind yourself that, with all those hills you’ve climbed, you’ve gotten better.

A grainy picture of me just minutes after completing my one and only marathon in May, 2014. Photo credit: a random woman at the finish line.