Environmental pollution and the precautionary principle

Written by: Anna Walsh

A sign posted near Choccolocco creek, which received much of the wastewater discharge from the Monsanto PCB plant. Source: the Anniston Star.

The town of Anniston, Alabama is dying. Entire neighborhoods have been abandoned, large swathes of land where nothing grows abound, and residents of all ages bear an astonishingly high prevalence of serious health problems. The source of Annistion’s troubles is no mystery. Between 1929 and 1971, Anniston was home to a large manufacturing plant that produced polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), chemicals that were once widely used in electrical equipment, lubricants, surface coatings, and several other applications. During this time, tens of thousands of tonnes of PCBs were discharged into the air, the water, and the open-air landfill near the center of town. In addition to being extremely useful in cooling and insulating applications, PCBs also turned out to be extremely toxic.

The Monsanto plant near downtown Anniston (undated photo). Source: The Anniston Star.

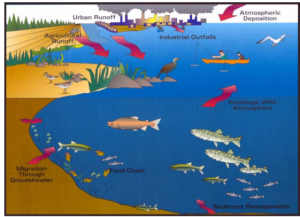

Though Anniston, Alabama continues to suffer among the worst impacts from PCB contamination, it is by no means an isolated problem. The converse is, in fact, true: because PCBs do not easily break down in the environment, they have spread globally and will persist for years to come. PCBs also biomagnify, which means that with each step up the food chain, from minnow, to trout, to humans, their concentration increases – which is particularly disturbing, given that PCBs are known to cause cancer in many animals and, most likely, humans.

Sources and transport of PCBs in the Great Lakes. Source: Hornbuckle, Keri C., et al. “Polychlorinated biphenyls in the Great Lakes.” Persistent organic pollutants in the Great Lakes. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006. 13-70.

While PCBs’ toxicity to humans and the environment was discovered several decades prior, PCBs were not banned in the United States until 1978. The phase-out may give the impression that this problem has been dealt with, but the reality is far more complex. Anniston is among the hardest-hit and still suffers from unusually high rates of crime, poverty, and mental and physical health issues, all of which can be traced back to the severe pollution. However, high levels of PCB contamination from improper or irresponsible use linger around the world, from New Bedford Harbor to Okinawa, Japan. Low-level PCB contamination is ubiquitous: PCBs have been detected in the Mariana Trench and in a majority of the Americans’ blood.

Unfortunately, the story does not end here. To fill the heat-resistant void left by PCBs, a new class of compounds swept in: polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). Production ramped up in the 1970s, peaking in the 1990s. At the same time, concerns were being raised about the environmental and human health impacts of PBDEs. By the early 2000s, several of the most commonly used PBDEs were also being phased out. As with PCBs, however, the phase-out came too late to avoid widespread environmental contamination and near-ubiquitous human exposure to this potentially carcinogenic compound.

At this point, you might expect that we’ve learned our lesson. And yet, the story repeats once again. PBDEs were replaced by a suite of chemicals and already, several scientific studies have shown that these replacements likely have similar environmental spread and human health effects as their predecessors.

It’s an all too common cycle. I chose to discuss flame retardant chemicals, but I could’ve told you the same story about many of the pesticides, industrial chemicals, even consumer plastic products on the market today. Straightforward solutions to this problem certainly exist; the difficulty lies in reconciling the need to minimize environmental harm with a sky-rocketing population that demands faster, larger-scale production of goods to keep up with our increasing consumption.

To address this problem, several international treaties and legal systems, including the European Union, aim to apply what is called the precautionary principle. The principle states that, “when an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically.”

In reality, this rather sensible-sounding principle is quite difficult to implement. For one, who is responsible for proving that an activity or chemical will not cause harm? It seems reasonable that those producing and profiting from a chemical should shoulder this burden, but there is an obvious conflict of interests here. Oversight by government agencies would be necessary to keep companies in check, but few countries have the resources, infrastructure, and legal framework necessary to implement such a system. And without regulations defining “safe” and “unsafe,” penalties for violators, and funding for enforcement, the entire thing will quickly fall apart. Still, models for reasonable success do exist, including the 1987 Montreal Protocol that led to the phase-out of ozone-depleting chemicals, and we would do well to learn from them.

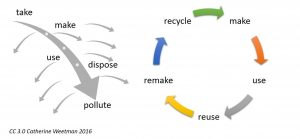

An alternative – and perhaps more promising solution – is to create a circular economy to close the loops that allow these chemicals to escape into the environment. In many cases, including the current hot button issue of plastic pollution, improper disposal (by industry, consumers, and others) and ineffective or even non-existent waste management systems are the main causes environmental pollution. Developing countries, especially, often lack the resources and infrastructure for proper disposal of pollutants (from plastic to PCBs), which leads to their release into the environment and increased human exposure. It is critical that, rather than placing blame and pointing fingers – because in this global economy, we are all complicit – those with more resources chip in. With a circular economy, we can divert these waste streams into something more productive: building blocks for new materials, fuel for our cars, and heat for our homes. At all levels, there is significant legwork needed to establish the requisite technology, regulations, infrastructure, and social norms; a circular economy will not happen overnight. In the meantime, there is plenty for us to do.

A schematic of a linear economy (right) – our current system – and a circular one (left). Source: Wikipedia.

We, as consumers, may not have the power to directly choose the chemicals that industry uses as flame retardants or how they dispose of their waste. But we most certainly can leverage the power of collective action to apply pressure on industry and the government. We can work to support and create policies – locally, nationally, and globally – that incorporate the precautionary principle to promote responsible use of chemicals and that push us closer to a circular economy. And, in our day-to-day lives, we can educate ourselves and others, buy products that were made safely and sustainably, and avoid those that were not (to the best of our abilities – think, “do what you can, not what you should”). Over the past few months, millions of people around the world have taken to the streets to demand immediate action against climate change – a problem that is intertwined with society’s out-of-control consumption. The collective willpower already exists to fix a broken system that has led to widespread environmental pollution and climate change. The next step is action.

The People’s Climate March in Washington D.C. in April. Source: CBS News.

References

O’Hagan, Sean. “Toxic neighbour: Monsanto and the poisoned town.” The Guardian, 20 Apr. 2018.

Washington, Harriet. “Monsanto Poisoned This Alabama Town — And People Are Still Sick.” BuzzFeed News, 26 July 2019.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. “Toxic Substances Portal – Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs).” Center for Disease Control, 27 Aug. 2014.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. “Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) Toxicity

Clinical Assessment – Laboratory Tests.” Center for Disease Control, 9 Aug. 2016.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. “Summary of the Toxic Substances Control Act.” US EPA, 10 Sep. 2019.

Gilbert, Steven G. “Precautionary Principle: The Wingspread Statement.” Collaborative on Health and the Environment, 2019.

Kriebel, D et al. “The precautionary principle in environmental science.” Environmental health perspectives vol. 109,9 (2001): 871-6. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109871

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. “What is a circular economy?” Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017.