Dead Storm Hunting: Fiji and Vanuatu

By: James Bramante, PhD student in the MIT/WHOI Joint Program

This blog is cross-posted on the Coastal Systems Group website.

Hills and mangrove forest near Vanua Balavu village, Fiji. Photo credit: J. Bramante

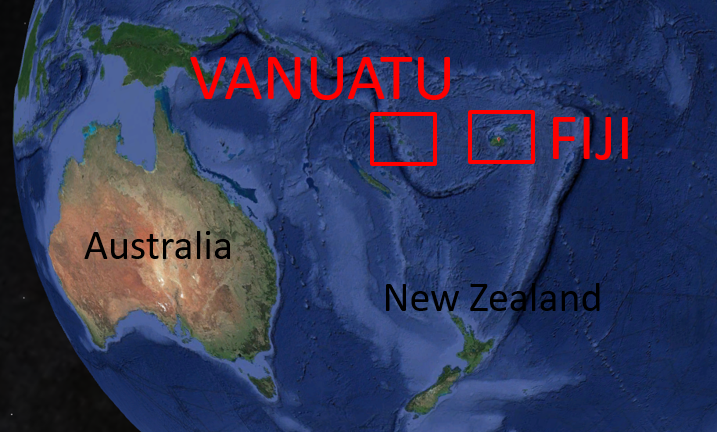

Fiji and Vanuatu are island nations in the tropical South Pacific.

There’s nothing like arctic weather to make you nostalgic for tropical fieldwork. During the past month, temperatures dropped to 5 F (-15 C) in Boston and Cape Cod. With wind chill it felt like -5 F (-20 C). I had the dubious fortune of bragging to my uncle in Alaska that for once our winter was harsher. Walking 20 minutes to and from work every day gave me plenty of time to wish I was back in Fiji and Vanuatu, extracting the remains of tropical cyclones long past.

Storm Chasing of a Different Kind

Dead cyclone hunting is one of the main activities of the Coastal Systems Group at WHOI. Tropical cyclones, (a.k.a. hurricanes, typhoons) are large, spinning storms that form over the ocean, increase in strength over warm water, and generate large wind speeds and waves that can devastate coastal communities.

Roofs and sand are not the only things moved by storms. These are just a few of the boats thrown up on shore in Port Vila Harbour during Cat 5 Tropical Cyclone Pam. The boats haven’t been salvaged since the storm hit in March, 2015. Photo: J. Donnelly

In addition to knocking down trees and ripping off roofs, cyclone winds generate waves that sweep over coastal barriers like beaches. The waves carry coarse sand that gets deposited as sheets in protected bays and lagoons. Without storm waves, only finer mud is deposited in these basins, making the sand layers stand out. Decades, hundreds, and thousands of years later, these sand layers remain preserved under thick mud, the only remains of long dead storms. By retrieving long cores of sediment, we can identify ancient storms, their frequency, and even their magnitude. We’re the muddier and usually less glamorous cousins of storm chasers.

Jeff Donnelly and Nicole D’Entremont at the beginning of our trip. It’s amazing how much the right pose on the deck of a sailing vessel can improve one’s glamour. Photo: J. Bramante

Fieldwork, Alpine Style

Traveling “light.” Normally our equipment fills half a shipping container. This trip we checked it all onto the plane as luggage. Photo: J. Bramante

In September 2017, we landed on Taveuni Island, Fiji prepared to tackle the field alpine style: fast and light. Minimal funding meant we couldn’t ship our large coring engines across the Pacific, so we made do with a hand-driven percussion coring system. To use this system, we attach a long, empty, aluminum barrel to the bottom of a circular anvil, and then lower it to the sediment surface on a strong rope. We use a second rope to raise and then drop a 50 lb “hammer” onto the anvil. The blows from the hammer push the barrel into the sediment incrementally, so that over an hour of back-breaking labor and hundreds of hammer strikes we can push the barrel up to 5 meters (~16 ft) into the sediment. Then the real work begins.

A 5-m barrel of sediment only weighs about 46 kg (100 lb), but when it’s stuck 5-m deep in mud it can take hundreds of pounds of force to extract. Without our heavy-duty electrical winch, we were forced to extract the barrels with a farm jack, also hand-operated. All of this work is conducted on a floating platform. Normally we use two 20-foot long inflatable kayaks to support the platform, but working alpine style meant we had to make do with a platform half that size supported by sea kayaks.

A sampling of our makeshift coring platforms from this trip. One positive side effect of alpine style fieldwork is that you get a chance to iteratively design and test field equipment. Photos: J. Bramante and J. Donnelly

At several sites our attempts to extract the sediment nearly sank our rafts and we had to let the sediment go. That feels a lot like this:

No evil uncles for us though, just gravity and disappointment.

Our poor transducer after TSA attempted to remove it for the umpteenth time. We managed a field repair, but upon returning home we found TSA had severed the cord completely. Photo: J. Bramante

The risks of alpine style fieldwork are numerous: lighter equipment breaks more easily, without spares you can’t afford to lose equipment, and lighter equipment means less mud can be retrieved. On this trip our percussion corer broke catastrophically four times, we were forced to abandon three barrel-fuls of mud or risk drowning, tampering by TSA destroyed our most expensive piece of equipment, and by the end of the trip we were too exhausted to function.

However, as with alpine style climbing, alpine style fieldwork allows you to move more quickly and achieve more objectives. Over four weeks, 400 km, and two countries we meticulously surveyed ten sites with a sub-bottom profiler (a sonar that tells you how much mud is at the bottom) and successfully retrieved mud from all eight sites where we made the attempt.

Sediment from one of our Vanuatu sites. You can see the remains of at least two storms in three event beds consisting of cobble-sized sediment surrounded by mud. This is one of the most stunning examples of storm deposits I’ve seen. Photo: K. McKeon

The Views

Below is a sampling of the sights at our sites to keep you warm during this frigid winter.

Cobia, Fiji

Cobia is an old volcano within a larger atoll-like reef (Budd reef). You can see layers of cooled lava that constructed the volcanic cone on the rock outcrop on the right. Photo: J. Donnelly

Bay of Islands, Vanua Balavu, Fiji

Limestone pillars covered in shrubs, the “islands” for which the Bay of Islands is named. Photo: J. Bramante

Waves and the tide have cut notches into each of the limestone pillars at water level. Photo: J. Bramante

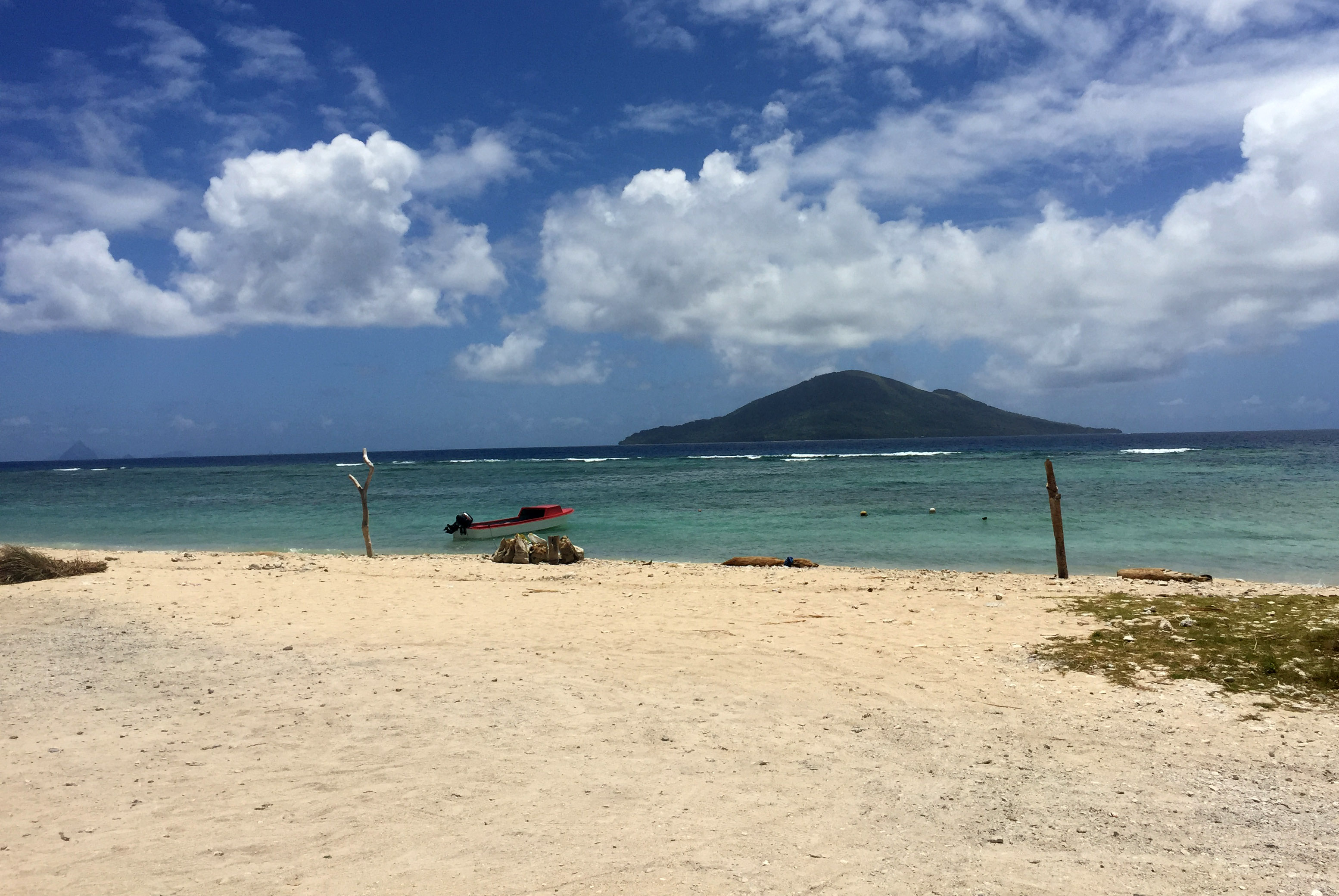

Emau, Vanuatu

Emau in the distance, an island with a dormant volcano. The bay there is sheltered by a very shallow fringing reef. Photo: J. Donnelly

Port Havannah, Efate, Vanuatu

The northern coastline of Efate Island, with stunning uplifted reef terraces outlined in red. These terraces are the remains of old coral reefs likely left above modern sea level by tectonic uplift. Photo: J. Bramante

Postscript

Fiji and Vanuatu were beautiful countries, whose residents were incredibly friendly and helpful at every step of our journey. All surveys and sediment extraction were conducted with permission from both federal authorities and local villages at each site. We are especially indebted to Dr. Krishna Kumar Kotra and his students at the University of the South Pacific, Emalus Campus, who helped us reach and extract sediment from our Vanuatu sites while respecting local customs and concerns.

Nicole instructing University of the South Pacific students how to use our sub-bottom profiler, pre-TSA destruction. Photo: J. Donnelly

James Bramante (behind students and farm jack) and Dr. Kotra (in life jacket) demonstrating the use of a modified percussion coring system to USP students. Photo: J. Donnelly