Children, your greatest [carbon] legacy

Written by: EeShan Bhatt

“Minus one”

I look towards my partner and direct her attention to some news coverage on the recent IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report. It details that the world has already warmed one degree Celsius relative to temperatures before the Industrial Revolution, and significant action is needed in the next 12 years to curb warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. A previously agreed upon target, 2 degrees Celsius, is now projected to have exponentially disastrous effects.

She agrees with a quick nod but counters, “But babies are so cute.”

We keep a running tally about whether we want to have kids. This started out as a fun game to discreetly point out cute babies (plus one) or cute babies crying (minus one), but it quickly evolved into a nuanced projection of what our life would be like if we decided to buck the norm and not have children. This conversation usually revolves around our career ambitions, financial stability, potential health complications (she is a pediatric physical therapist), familial connectivity, and freedom to travel, though recently, a new question has irritatingly pushed its way to the top: should we even have children given the current climate crisis?

Let’s say my partner and I will have children (natural or adopted) in the next 12 years. Said children would grow up with high carbon levels and heating that are past the point of no return. The amount of risk and uncertainty that this child would have to endure, from food shortages, water scarcity, ecosystem collapse, heat waves, sea level rise, and pollution, is unprecedented, and making that choice for them is cruel and selfish. Why bring a child into this world in the face of such dire change?

Others argue, however, that the best way urgent action will be universal is by labeling it as “for our children.” If there is something people can agree on, across countries and cultural norms, is that we should make the world a better place for our children. If people stop having kids, especially those who are passionate about the climate, it is a tacit sign of defeat. Having children is always a risk, but it’s still worthwhile. It’s a carrier of hope and real commitment to not giving up on Earth and framing the fight against climate change as the fight for each other.

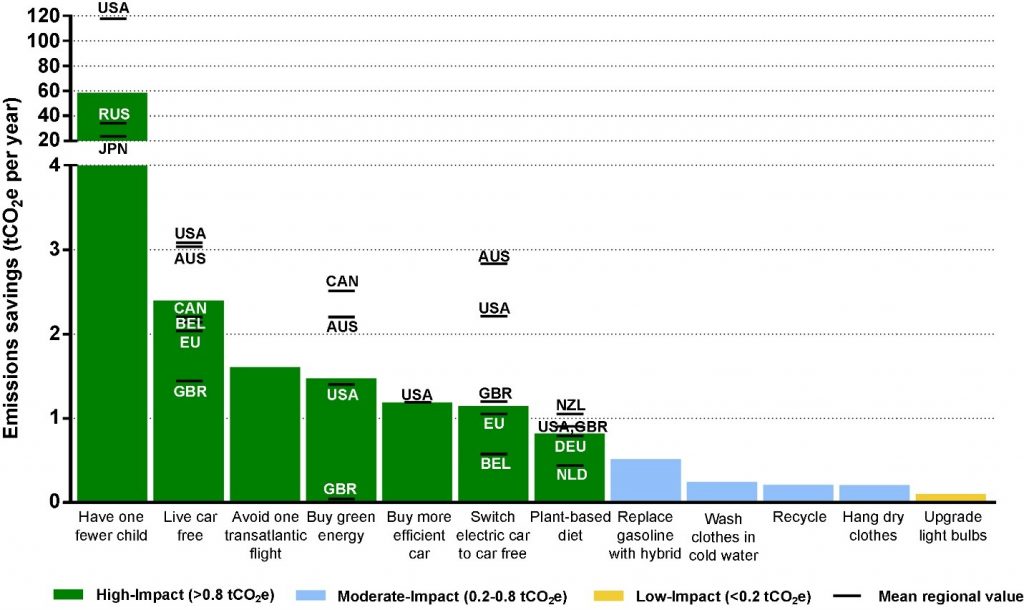

Take a look at this recent study (Wynes and Nicholas, 2017) though– it shows that for an average human, having one fewer child is the single most impactful decision you can make to reduce your carbon emissions.

Forget being vegetarian, or taking public transit for the rest of your life, or making all your cross-country business meetings and vacations virtual. The carbon savings per child are orders of magnitude higher than anything else you could probably do in your life. And this is ignoring the fact that your children may have more children, or rather, your choice to have a child and its carbon footprints propagates beyond your lifetime. Another study (Murtaugh and Schlaux, 2008), shows that the cumulative carbon footprint of a person’s descendants, weighted by their relatedness to the ancestor, would far exceed their own carbon emissions. By running a stochastic statistical model designed to simulate the probability of passing on your own genes coupled with projected carbon emission rates, they suggest that your carbon footprint increases 5.7 times with each child you raise. At the very least, people need to consider how their reproductive choices make an impact on the global environment, now and for the future.

But, if we’re looking at orders of magnitude and impact, then having a child is orders of magnitude less than what is driving climate change: ; 100 companies produce 71% (it’s only fair to point out that these companies are not producing greenhouse gasses for fun and that these statistics include downstream use – they are often the byproduct of several dependent industries, the most predominant being increasing global agriculture). Furthermore, their impact is measured in Gigatons (10^9) compared to the tons above. If people may forego having children based on scientific facts, then they should have access to all the data and be practical about it. There’s no need to be a martyr.

Every little action helps. It’s defeatist to look at the overwhelming complexity of carbon emissions and think your individual emissions are insignificant. Little actions will add up when they become more commonplace and accepted. So maybe you have one fewer child instead of none, but where do we draw the line – two, three, four?

The UN offers this explanation on reproductive rights: “These rights rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. It also includes the right of all to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence as expressed in human rights documents. In the exercise of this right, they should take into account the needs of their living and future children and their responsibilities towards the community”.

Climate change and the prospect of having children is a multifaceted issue. It overlaps with the healthcare and education sectors, the current debate over birth control, the growing climate driven genocide and migration, and the disproportionate health effects on urban and low-income children (Bartlett 2008). Perhaps most poignantly, it twists the human condition: pitting humanity’s survival against your own genepool’s.

I, and many others in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program, pursue a higher degree in oceanography because we are passionate about the environment and know climate change is one of the greatest issues our generation will face. But it’s also becoming increasingly clear that it’s not just oceanographers or climate scientists that should play an active role in mitigating global warming. It’s called global warming for a reason, and everyone, from an individual citizen to the largest governments and businesses, need to work together for our collective future, not rationalize a myopic narrowmindedness.

It’s also important that all of us start to have what are generally private conversations in public. In the public eye, these issues become normalized, understood, and actionable. Opening the door on this rather difficult conversation is the first step towards weighing the multitude of factors of having a child and making that choice ethically – whatever that means to you.

Do we want to have kids? Definitely. Will we? Who knows, I’ve lost count already.

—

EeShan Bhatt is a NDSEG Fellow at the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in the Mechanical Engineering and Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Departments. The views expressed in this post are entirely his own.