Harry Potter and the 12-minute conference talk

One of my favorite podcasts, Harry Potter and the Sacred Text, begins each episode with a segment called the “30 second recap”: Vanessa and Casper, the two hosts, get 30 seconds each to summarize everything that happened in a single chapter of a Harry Potter book*. They start out speaking normally, covering everything in detail, but as the seconds tick by they speed up and raise their voices, often ending with a frantic shout of some crucial point in the story. It’s hard not to laugh when a particularly complex chapter leaves them gasping for breath, but at the same time, I can sympathize: we scientists do very similar things at academic conferences.

I went to New Orleans for a week in early December for the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting (AGU for short), a conference that draws nearly 25,000 geoscientists annually from across the country and around the world. At AGU, oral presentations are given as 15-minute talks—and that 15 minutes includes time for questions and for speakers to walk up and down from the podium, so really, you only get about 12 minutes to give your spiel. An AGU talk is a prime opportunity to share your research with an especially large and broad audience of fellow scientists, so you want to use those 12 minutes wisely and well. Lots of people (myself included) struggle with the brevity of AGU talks. The content is a little different, but we’re dealing with the same problem as Vanessa and Casper are on their podcast: how do you convey a lot of information in very little time?

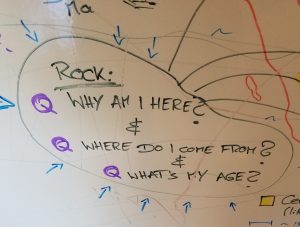

An AGU attendee (not me, unfortunately) drew this profoundly curious rock on the “Sharing Science” wall.

This year, for example, I gave a talk at AGU about a 70-million-year old chunk of seafloor in the Pacific: its structure, its history, and how we can learn about those things using seismic data. I’ve been working on this research since I started graduate school over three years ago. How can I fit three years’ worth of work into 12 minutes? And if that’s hard, then how can I even begin to cover the 70 million years’ worth of stuff that has happened to these rocks in 12 minutes? Even if I spoke as fast as an Oscar-winning actor trying to thank as many people as possible before the music starts to play, I couldn’t get to everything about this work within the bounds of an AGU talk.

Even venerable speakers at well-attended conference sessions may occasionally put too much text on their powerpoint slides.

Speakers have all sorts of strategies for dealing with this kind of time compression, intentional or not: they talk faster, skip over excess powerpoint slides, or just keep going as moderators stand up and hover behind them, too polite to literally chase them off the stage when their time is officially up. But those are hardly optimal solutions—a short talk shouldn’t need to be a rushed talk, or an abbreviated talk, or an actually-slightly-too-long talk. Taking the 30 second recaps as my example, here are the three things I think are most important for making good use of your 12 minutes:

First, know how much time you have, and practice within that time. After three and a half books’ worth of podcasts, I suspect that Casper and Vanessa have a very good sense of how long 30 seconds is. The more you practice speaking within your time limit, the easier it gets. Some people will run a talk five times before the actual event, some fifty times; there’s no right number to hit, but it’s generally true that zero is not enough.

Perhaps the dulcet tones of this accordion-playing reptile would be an appropriate background track for a conference talk in NOLA? But no – background music is generally frowned upon in academic circles.

Second, think about how you sound. Podcast hosts are stuck with audio, so varying vocal timbre or volume, changing your speaking rhythm, or throwing in some sound effects is especially important to keep peoples’ ears tuned in. Those same tricks apply when you’re speaking to a live audience (though you might skip the sound effects for an academic conference). Nothing puts a room to sleep like a droning voice, even (especially?) when you have powerpoint slides.

Finally, the content: distill it. In recent episodes of Harry Potter and the Sacred Text Casper has taken to emphasizing the activities of Percy Weasley in his 30 second recaps, because he has apparently decided that that’s the most important information to convey. You may or may not agree with that, but you have to admire the strategy, since Percy’s activities are easy to cover within 30 seconds (for those of you unfamiliar with the Harry Potter books, Percy is definitely not a major character). The best tool we have for giving short talks is our own discretion. Does the audience need to know what you found out? Yes. But do they need to know every turn and twist of the circuitous route you took to get to that result? In general, no. Your job is to find the core of your topic, put it out there, and arrive at the 12 minute mark with your story told, your breath intact, and 70 million years’ worth of geologic history—or 2,000 years, or 3 billion, or just a day in the life of Percy Weasley—neatly folded into your time slot and firmly planted in your audience’s minds.

* Full disclosure: one of the producers of the show is a friend of mine from college (hi, Ariana!)