Getting a PhD doesn't necessarily mean that one has to enter into an academic career. There is an ocean of opportunities available to graduate students; yet finding the right path can seem like a daunting task. Through our new Alumni Spotlight series, the Through the Porthole crew is aiming to highlight the variety of careers that graduates of the Joint Program have pursued.

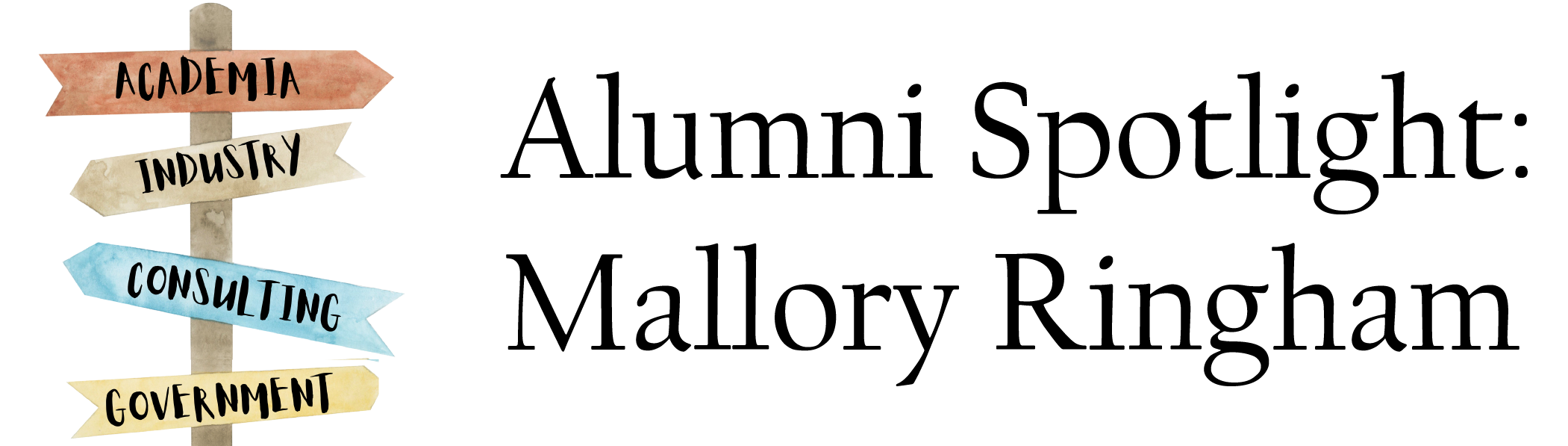

In our second edition of the Alumni Spotlight series, we sat down with MIT-WHOI Joint Program Alumni Dr. Mallory Ringham, who is currently working as Lead Oceanographer for Ebb Carbon, a carbon dioxide removal (CDR) start-up. In her PhD thesis, Mallory tackled interdisciplinary problems regarding carbon cycling dynamics through the development of in-situ observation studies and sensor development. After defending her thesis in 2022, Mallory went on to a unique postdoctoral position at Stony Brook University that spanned academic research and industry consulting. In this interview, we dig into the experiences and opportunities that influenced Mallory’s career path and gain insight into some avenues available for graduate students to transition from academia towards industry. Read on to learn more about her journey and to hear Mallory’s insights into the rapidly evolving field of CDR!

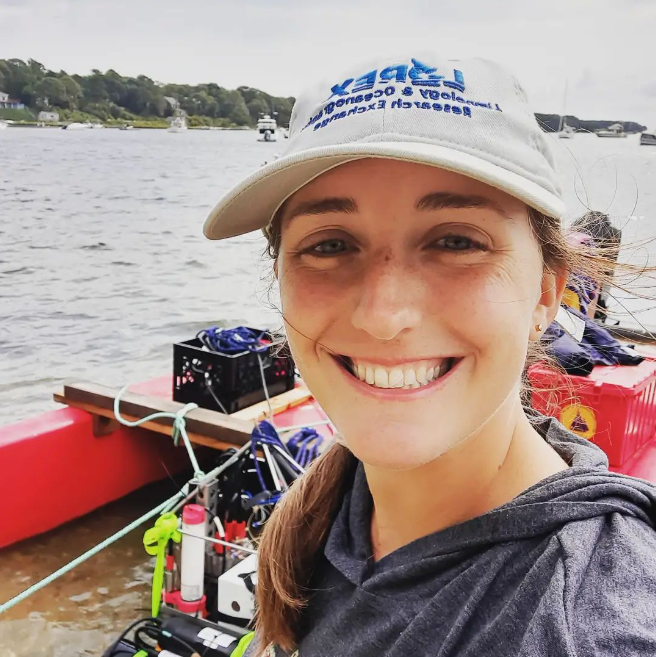

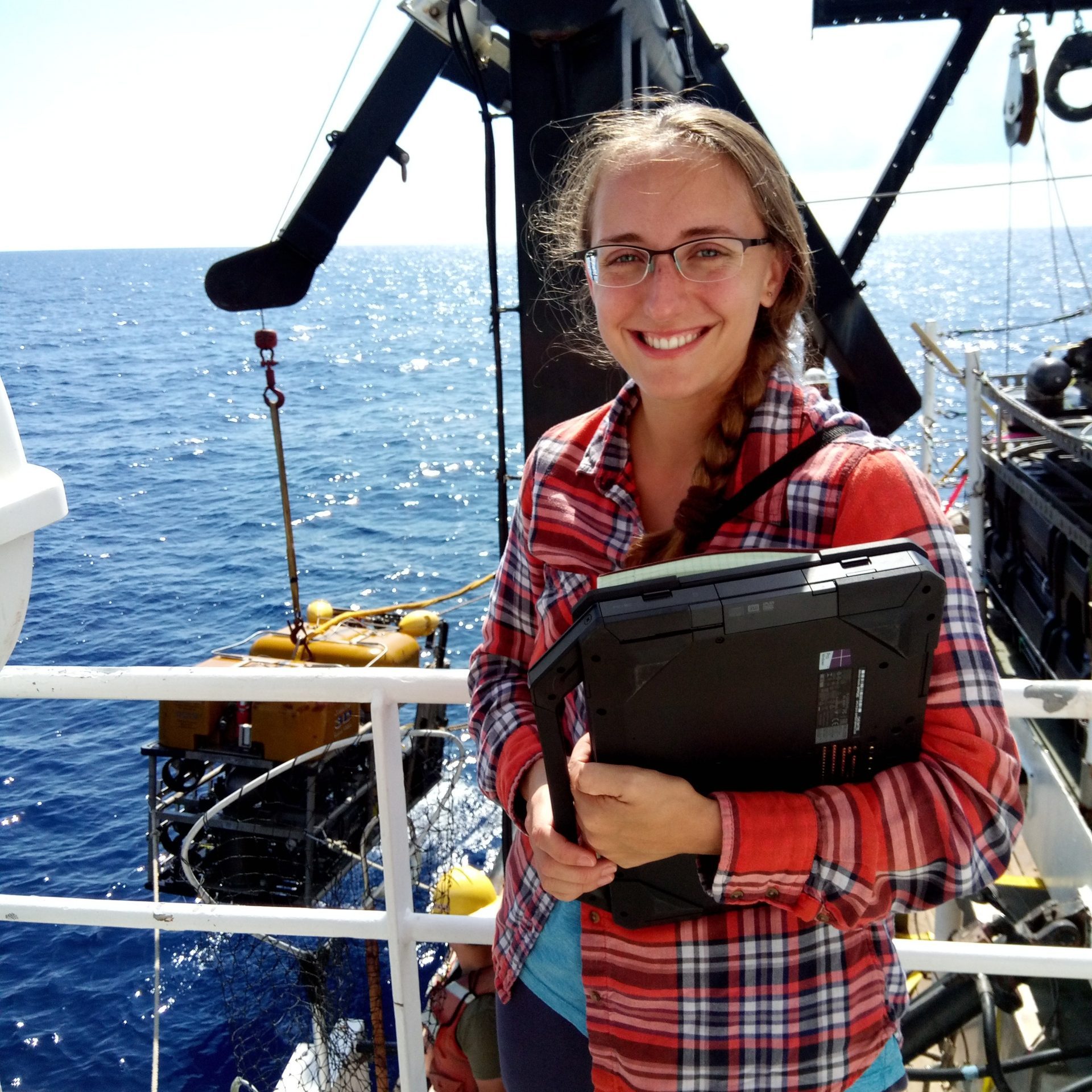

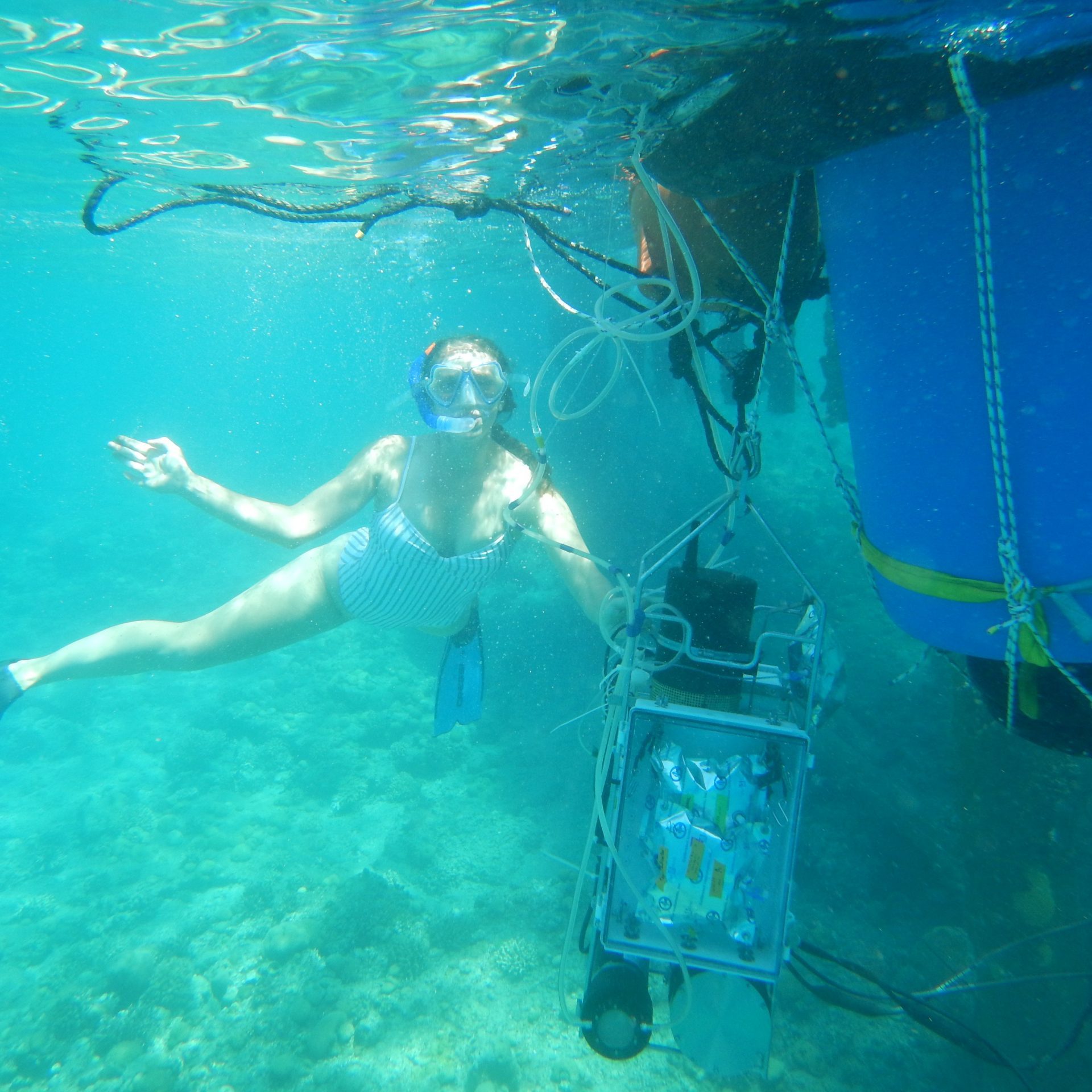

Mallory completed her undergraduate and master’s degrees at Syracuse University in New York. Her interest in the geosciences was first sparked in undergrad when she took earth science classes that allowed her to travel for field work. After earning her B.S. in Physical and Chemical Engineering in 2013, she went on to complete her M.S. in Earth Sciences. Her Master’s research focused on clumped isotope paleothermometry, an important technique that geochemists use to reconstruct past climates, and brought her to places like the Andes of Argentina and Chile for field work. In addition to her time spent out in the field, Mallory also worked in a variety of labs that allowed her to gain experience and exposure to a wide range of disciplines, both in science and engineering. After completing her M.S. in 2015, Mallory decided to dive into Chemical Oceanography for her PhD and joined the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in 2016. Mallory’s PhD thesis focused on the development and deployment of autonomous sensors to measure inorganic carbon, pCO2 and pH. Her work on sensor development was aimed at improving our ability to measure and understand the inorganic carbon cycle in a variety of marine settings, and has broad implications for improving our understanding of the global carbon cycle. Throughout her academic journey, Mallory has always been motivated by a desire to be part of the climate change solution.

Like most PhD graduates, Mallory used her postdoc as a stepping stone before starting a full-time position. However, unlike most academic postdoctoral positions, Mallory’s was a unique blend of external consulting and academic research. Her official title at Stony Brook was postdoctoral associate in the Electrical Engineering Department, which may seem like a strange place for a Chemical Oceanographer to end up, especially considering that there is a well-known School of Marine Sciences at Stony Brook. Instead, Mallory was part of the Electrochemical Ocean Acidification Laboratory, led by a physicist in the Electrical Engineering Department and based at the Flax Pond Marine Laboratory, which is managed by the New York Department of Conservation Lands. This unique postdoctoral position allowed Mallory to blur the lines between academic, industrial, and government research, and allowed her to work with people from a diversity of backgrounds and disciplines. Another unique aspect of her position was the chance to be a consultant for Ebb Carbon, a startup company founded by her postdoc advisor that focuses on electrochemical carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

Working as a consultant for external groups is not a common experience that many graduate students and postdocs are able to have, in part because of institutional policies, but also because many people don’t know if it can be a viable option within their respective fields. For Mallory, her hybrid postdoc allowed her to be perfectly positioned for her current role as Lead Oceanographer for Ebb Carbon. With the rapid rate of growth in the CDR industry, it’s likely that graduates will have increasing access to alternative postdoc opportunities that blend research and consultation. In general, the relatively young CDR field offers geoscientists an exciting opportunity to apply the interdisciplinary skills and knowledge they gained in graduate school to help develop scientifically sound climate solutions.

Mallory didn’t always picture herself as a lead scientist for a startup CDR company. In fact, her career goals drastically shifted throughout her PhD as she gained insight into the realities that accompany the career of an academic researcher. Up until the third year of her graduate program, Mallory’s goal was to pursue a position in a federal lab, like those run by NOAA, NASA or USGS. However, as she spent more time working with scientists from a range of backgrounds and career paths, she started to realize that the downsides and sacrifices of staying in academia didn’t align with her personal goals. Early career scientists trying to land a faculty position face many of the same pressures that prospective graduate students and postdocs face–location, institutional culture/resources, relocating with a partner, financial considerations, etc. Finding a position that can fulfill each of those needs can be extremely difficult–if not impossible in many cases. In addition, there’s also the chase for tenure that underpins the typical academic faculty career track. After witnessing the stress and sacrifices of her academic colleagues, Mallory started to consider alternative career pathways.

"All of the downsides became really apparent when I was that many [3] years into the program. But when I started, I was like, I would like to be a scientist. And this is what scientists do. They go, and they get their PhD, and then they go and …get tenure somewhere; and I was not aware of what sacrifices that meant. Towards the end of the program I was in contact with a lot of people who were faculty for a year or two and were in that tenure track pipeline and then left for industry because their jobs didn't pay them enough for the hours they were working. They were expected to live somewhere where their partner couldn't get a job. They were dealing with grad students who couldn't afford to live. Their postdocs were on food stamps. You know, all these sorts of social issues that became really apparent, and I was like, “I don't want to deal with it anymore.”

Mallory also started to compare her own personal work style and goals with those required of an academic faculty.

“... you need to be a very specific type of person. You need to be really good at and really enjoy writing proposals, and you need to be really good [at] and really enjoy writing research papers, and you need to be really good at suggesting big idea things that get you the money to do what you want to do. And I think that is not the vast majority of science and the workforce. That's just not what most of us are good at, and it's not what most of us should be good at.”

Once Mallory began connecting with Joint Program alumni who were in non-academic positions, she started to let go of the typical stigmas that surround scientists who move into industrial positions.

“The people that I knew who were leaving for industry were all often considered by the scientific community as almost sellouts. Like, they're going to go and do a job to get paid and they don't care about the science anymore, and I feel like that opinion has shifted in the scientific community. And I think it's shifted largely because more and more people are seeing that the reasons people leave for industry are varied, and it's not like ‘I just want to get a lot of money…’ so I feel like the difference in respect around career choices has shifted over the past few years and now it's far more acceptable to be a scientist in industry.”

In Mallory’s opinion, her colleagues in non-academic positions generally seemed to have better work-life balance, more options for positions (in terms of geographic/social considerations), and better pay. Mallory also pointed out that the nature of working as an industrial scientist seemed to allow for more time to be spent on actually doing science, in addition to faster paced research.

“The pace of work as an academic is very different compared to the pace of work in an industry where if you want to just try something, you buy equipment and you do your experiment. But in academia, you know you need to apply for research permits and for all the proposals, and it might be a year before you find out you could do your proposal and then you have to hire a postdoc and they don't show up for eight months, you know. It's a completely different pace.”

Once Mallory decided to begin the pursuit of a non-academic position, she was pleasantly surprised to find that her research focus (inorganic carbon cycling dynamics and sensor development) had positioned her incredibly well to join the rapidly growing field of ocean-based CDR.

“... it's a perfect thing to work on for a PhD right now. Because there's so much money pouring into this space.”

Mallory ended up finding her postdoc/consultant position through an alumni of her PhD advisor’s lab. When asked about resources or experiences that she could share with other students interested in finding non-academic positions, Mallory stressed the value and importance of taking advantage of your program's alumni network. If there isn’t a formal network set up, you can take it upon yourself to cold call/email previous graduates who are working in a relevant field. Additionally, Mallory suggests making use of your institution's career resources, especially for assistance in resume building, interviewing, negotiating, etc.

A final piece of advice from Mallory is to start having conversations early and frequently with your advisor, labmates and peers about what your eventual career goals are.

“I don't think that in the course of my program throughout the Joint Program that people asked me what I wanted to do as a career more than one or two times… Those sorts of conversations may come up organically with really good advisors or labs, but they don’t come up for everyone.”

Graduate students and postdocs can also communicate with their academic programs office about the types of speakers and career panels you would like to see to better support your goals. In fact, Mallory and a handful of other JP Alumni are actively working to establish a more formal network of early-career scientists in the climate solution space to help enable and broaden these types of conversations and opportunities. While that specific network isn’t quite ready to be broadcasted to the general public, Mallory did pass along information about the International Carbon Network for Early Career (ICONEC). ICONEC is nested within the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON), an international network aiming to connect scientists and encourage collaboration. Groups like ICONEC offer an excellent space for early career scientists to connect and support each other, especially within the rapidly evolving field of carbon research.

Overall, Mallory’s journey is an inspiring example of how a recent PhD graduate can successfully bridge the gap between academia and industry. With her in-depth knowledge of engineering, chemical oceanography and a keen interest in helping to mitigate climate change and improve the world around her, she is poised to make a significant impact throughout her career.

Read more of Through the Porthole Issue #9

Learn more about Through the Porthole

Learn more about the MIT-WHOI Joint Program