Introduction

It’s summer in Antarctica, the temperature’s hovering in the 30s and the wind is blowing. And it’s winter in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where the… temperature’s hovering in the 30s and the wind is blowing. We’re Zooming with Shavonna Bent, a 5th-year student in Marine Chemistry in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program. Shavonna is currently at Palmer Station, an American research station in Antarctica, where she’s been since November, and will be until April. Shavonna took a little time out of her busy work day to tell us what she’s up to, what’s going on at Palmer, and when she’ll next see fresh lettuce.

Shavonna’s Research Background

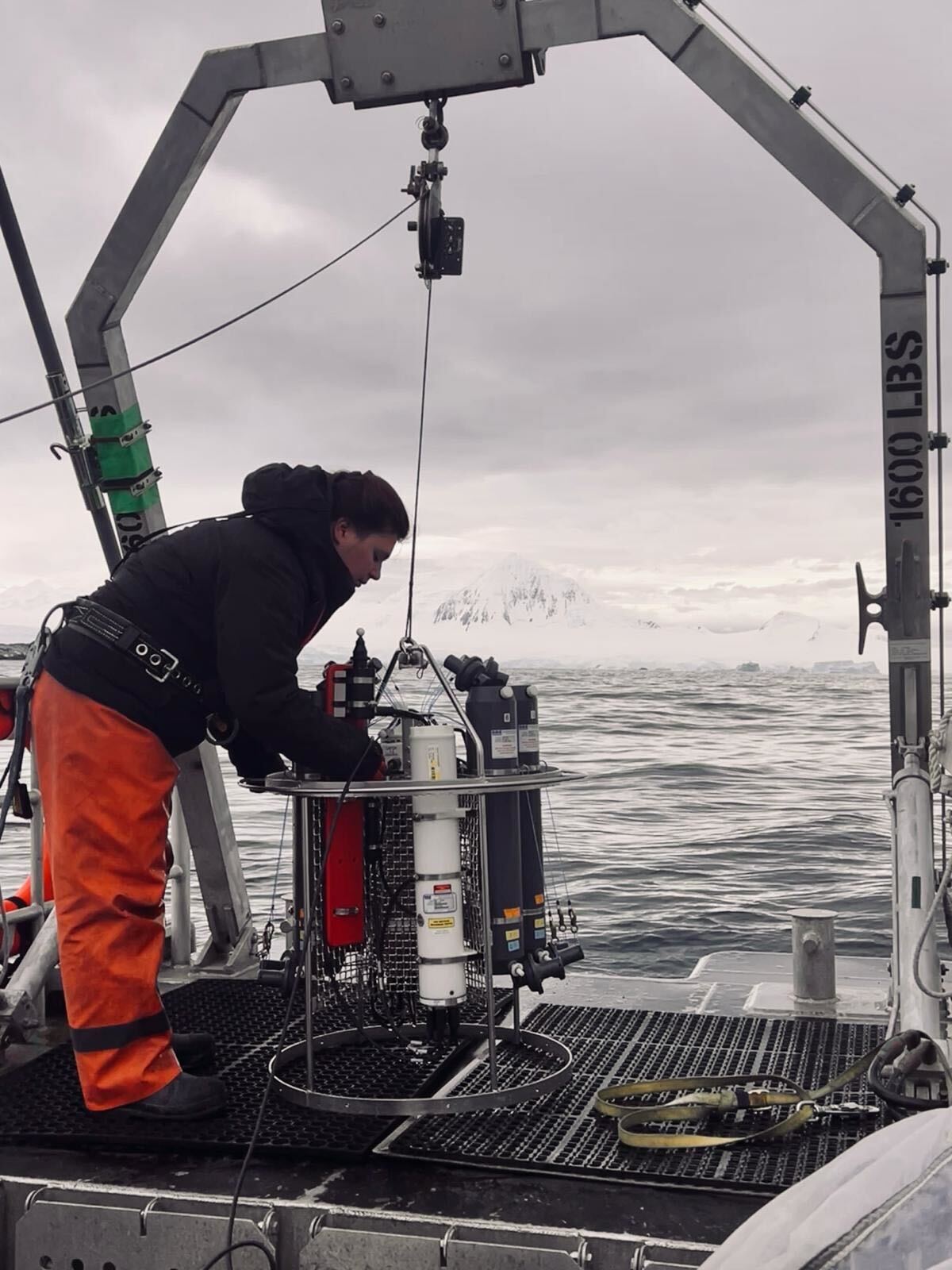

Shavonna got her start in research working in a microbiology lab in college, then did an REU at WHOI with Amy Apprill and Colleen Hansel where she mainly did lab work. She was interested in doing fieldwork in graduate school, so she applied to work in and then joined Ben Van Mooy’s lab. During her first fieldwork experiences at sea, she was trained on how to lead deck operations including instrument deployment and recovery. Her first training cruise was in the Gulf of Maine, and she went on to lead a team in Hawaii. These experiences helped prepare her to be a group lead for a 6-week long research cruise on the R/V Gould as a part of the Long Term Ecological Research project (LTER) in Antarctica. The Van Mooy lab has been responsible for collecting a series of core water column measurements that have been recorded for the past 20 years. “Consistency in the dataset is really important, so they designate a group lead for that. Last year was the first year that our group took over from a previous scientist, so part of my job was to write out the protocols so anyone who wasn’t trained by the previous crew could do it.”

As a leader for the LTER project, Shavonna was responsible for quality control, managing the sampling protocols when weather and other adverse conditions forced them to adapt, and communicating with the scientists back home. “They don’t prepare you for management!” Shavonna commented. She knew it would be a stressful experience, but also called it “one of the most empowering experiences of graduate school.”

At this point in the interview, a ghostly intercom came on at Palmer Station. “Safety meeting is happening for a mysterious topic called… ‘stacking safety’” reads out a voice from the ether. “I went to ladder safety last week, and it was hilarious.” Shavonna confides. Something she returned to often was that the people you are with in the field determine if things like safety trainings are fun or a chore - community is key.

Anyways, back to the glory and pitfalls of leadership. Shavonna took pains to improve organization, learning from any negative situations how to improve things for future teams. “The more time I spend in the field, the more empowered I feel. I do know this stuff! And I’m a good scientist and I know how to navigate challenges in the field. We’ve had so many things go wrong, and we’ve dealt with them! And I’m in a place where I can think of a solution.”

After her stint as a leader on the research cruise, Shavonna realized she would be interested in spending a longer period of time in Antarctica, although not on the R/V Gould. She returned in November 2023 for a 6-month stint as a scientist for Palmer Station LTER, where she participates in a variety of research activities.

What is LTER?

The question I bet you’re all wondering is “what is this LTER you speak of?” Yeah, I was thinking the same thing too… Palmer Station is one of 27 study areas for the Long Term Ecological Research (LTER, for short) project supported by the US National Science Foundation. A polar marine biome is a very unique area and is more sensitive to climate change than many other biomes - hence why scientists want to study it over long periods of time. At Palmer, there are numerous different facets of research taking place all led by different scientific groups. Shavonna is part of the Microbial Ecology and Biogeochemistry program led by Ben Van Mooy; however, there are other programs that range from seabirds to Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Palmer LTER’s mission is to continually collect long-term ecological datasets, but it also serves as a home base for scientists conducting shorter-term studies in the area, which can be contextualized by the long-term datasets.

What is it like being on Palmer Station?

Palmer Station is the smallest of the 3 year-round research stations located on Antarctica (the others being McMurdo Station and Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station). Palmer has a grand total of two main buildings on its campus. One building houses the science laboratories, dining hall, and dormitories. The other building, called the garage warehouse and recreation, houses the generator, bar, gym, and more communal gathering areas. Sounds like all their bases are covered!

Palmer Station is nestled on a tiny island off the western side of the Antarctic peninsula - so, pretty remote location, if you ask me. However, Palmer defies the typical deserted island trope by bustling with the activity of scientists and staff from across the US who have gathered together for the sake of science! During the field season, the Antarctic summer (where it’s a balmy 30°F and windy), upwards of 40 people live and work together on the island. Aside from scientists, the station brings down a support staff to handle things like food preparation and waste management. Everyone on the station has to wear many hats, as there are no dedicated janitorial staff. Tasks such as cleaning the station are handled using a bucket with a list of tasks on slips of paper - on Saturdays, you pick a job out of the bucket and get cleaning!

Safety and Training

What kind of training do you need to be a scientist in Antarctica? When you’re working in a remote location with risks such as cold water, exposure, and ice, safety is paramount. There’s tons of training to complete, continual safety check-ins, and loads of safety gear. An ocean search-and-request team is always on station, and ready to deploy in case of any accident at sea. One of Shavonna’s main research activities involves single-day research cruises for sampling. “This year we think there’s been an ice sheet that’s collapsed, so I had to learn how to drive a boat by an iceberg… terrifying.” Shavonna’s main research vessel for day-to-day research trips is the R/V Hadar, a 32-foot rigid hull inflatable boat with an A-frame and winch. Unfortunately, it was out of commission for a few months, and she had to complete her sampling using 12-foot inflatable Zodiacs, with no winch, requiring her to haul floats in by hand. “I’ve never been stronger in my entire life.”

How does Shavonna balance being a grad student and scientist?

So, the burning question is: How does Shavonna manage to juggle two roles— one as a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program and the other as a scientist for the Palmer LTER group? As part of the Van Mooy lab at WHOI, Shavonna is broadly interested in lipids: she studies how phytoplankton utilize these energy-bearing molecules and their importance in the context of carbon export and storage. Specifically, Shavonna has two projects that she is working on in Antarctica that will contribute to her thesis. The first is a collaboration with the scientists studying penguins at Palmer (dubbed, the birders). The birders are collecting penguin fecal matter for Shavonna so she can look at the lipidomic profile to determine what the penguins are eating and digestion efficiency. Secondly, she is doing a diel time series (taking samples every 6 hours over the course of 24 hours) where she will filter seawater to measure the lipid, carbohydrate, and particulate organic carbon (POC) composition of phytoplankton. Phytoplankton harness their energy through photosynthesis (which requires light) and Antarctica goes through intense periods of 24-hour darkness and 24-hour light. Shavonna will conduct this experiment during different light periods in order to fully understand how phytoplankton are responding to this intense variability. Although she won’t directly use all of the data she is helping to collect for the LTER project, she will be able to compare all her work to the robust dataset that results from the Palmer LTER scientists’ work.

Is it worth it?

Living on a remote island for upwards of 6 months sounds scary - but Shavonna is doing it. And she’s doing it exceptionally well. Being such a small science hub, the people who work there become incredibly close with one another.

“Living on Palmer Station is like living with a big second family. [We’ve done a really great job at] creating a community [with] some of the best people I have ever met.”

Since arriving to Palmer in the beginning of November, she has missed Thanksgiving, Christmas, and the New Year at home. Although the people working on Palmer do a great job at building community, she claims her mom “might murder [her] if she’s not home for Christmas [2024].” On top of missing home, there’s other things she misses. “I really miss lettuce. So much. I want a salad.”

Read more of Through the Porthole Issue #11

Learn more about Through the Porthole

Learn more about the MIT-WHOI Joint Program