We live on an ocean-planet. More than 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, and 96% of that water is held by the Earth’s global oceans. Many humans are obligate landlubbers, and as a consequence, have few opportunities to experience the vastness and mystery of the open ocean.

Sea-going oceanographers are some of the select few on the planet who are given the precious opportunity of immersing themselves in the marine realm. Oceanographers exist at the edge of human knowledge and discovery, living on the surface of Earth’s final frontier. In this special two part series of “Stories at Sea”, we will dive into the shared, yet differing experiences of MIT-WHOI Joint Program students Chloe Dean and Zephyr Girard. Both students joined the research expedition VIISTA, AKA Viral Infection at the Interface of Sinking, Turbulence and Aggregation, on the University of Hawaii’s Research Vessel (R/V) Kilo Moana. The roles and experiences of each student differed greatly, which is why we are excited to highlight their individual perspectives! Chloe's story, which centers on the experience of someone new to life at sea, provides a distinct contrast to Zephyr's story as a more seasoned oceanographer. Read on for Chloe’s personal reflection about the month that she spent living in the largest ocean basin on our planet.

The Ocean is so Big, and Viruses are so Small…

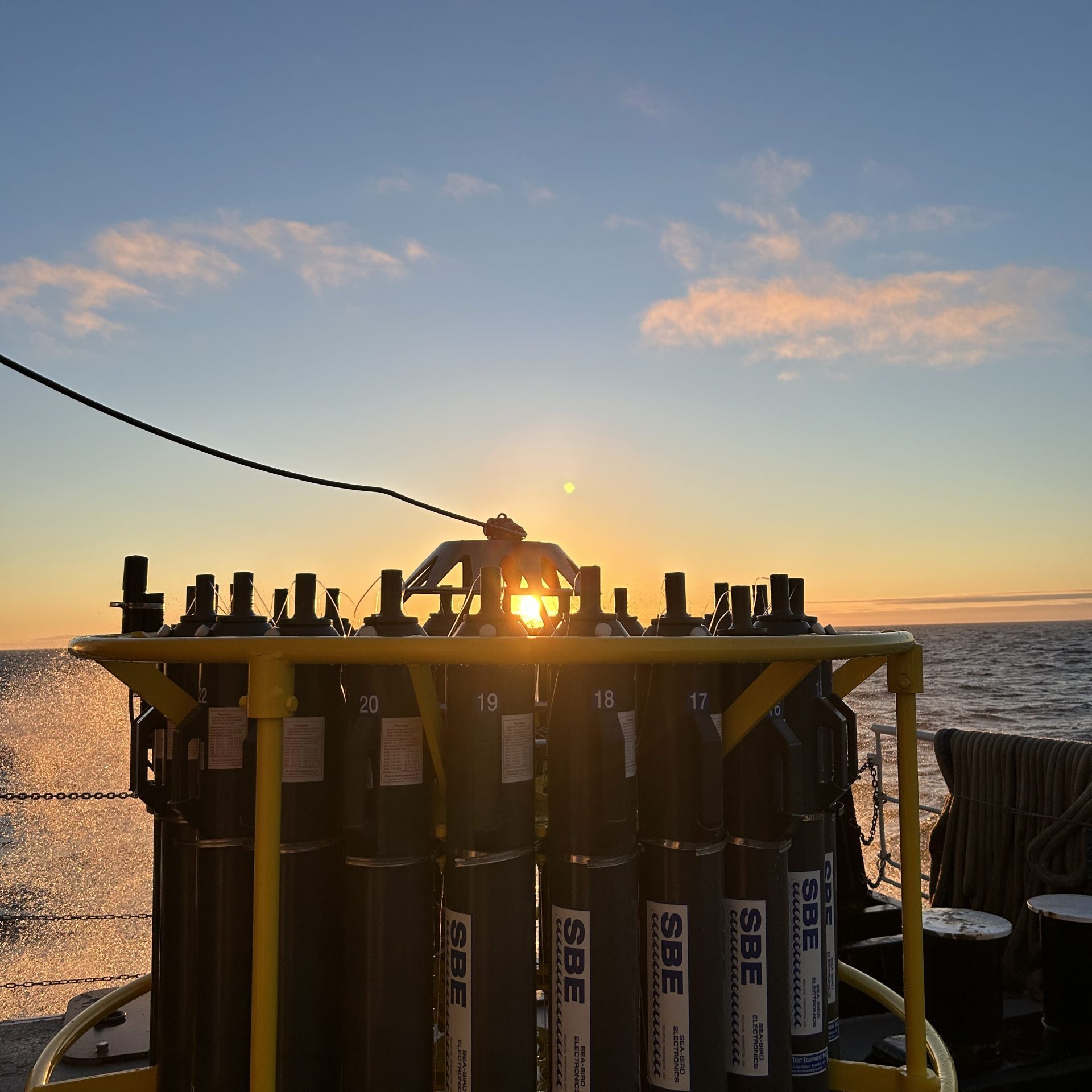

The 30-day cruise departed from San Francisco Bay on May 28, 2024 and returned on June 28, 2024 (and yes, we got to sail under the Golden Gate bridge… 6 different times!). This research expedition was part of an ongoing collaborative investigation into the possible role of phytoplankton viral infection in particulate organic matter formation and sinking. It has long been understood that viruses play an important role in marine biogeochemical cycling, which is a technical term for the study of elements that move around the Earth through biological or geological transformation processes. In the field of biogeochemistry, there is a hypothesis called “viral shunt,” where virally-infected cells burst and release their organic matter and inorganic nutrients to their surrounding environment. The VIISTA research expedition focused on the “viral shuttle”, an idea that virally-infected phytoplankton cells might also produce extra mucus (like a human with a cold), and that groups of infected cells might use this mucus to stick together to form an organic particle that can sink (unlike a human with a cold). The researchers on VIISTA wanted to explore how the “viral shuttle” may contribute to the transport of particles from the surface to the deep ocean, a process called the “Biological Carbon Pump (BCP)”. The BCP contributes to the Earth’s natural climate control processes, by modulating atmospheric CO2 concentrations and contributing to the long-term storage of carbon in the ocean.

“To live on the land we must learn from the sea

To be true as the tide and free as a wind swell

Joyful and loving in letting it be”

John Denver, “Calypso”

Chloe Dean, a fourth year Chemical Oceanography PhD Candidate working in the Subhas Lab at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, has always been driven by a love of natural environments (and quotes from John Denver’s ever-inspiring “Calypso”). To Chloe, the pursuit of knowledge about our natural world is the strongest way we can express our love of nature. This is a key driver in her motivation to pursue sea-going research, despite her propensity to get violently motion sick, even on stable ground. Her research focus was a bit tangential to the primary cruise goals, as she was tasked with interrogating the response of natural phytoplankton communities to a proposed marine Carbon Dioxide Removal (mCDR) strategy called Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement (OAE). While she was also there to assist with the main cruise operations by collecting samples for particulate inorganic carbon export, her main task was to conduct a series of deck board incubations where she modified the carbonate chemistry and closely monitored the response of marine critters using a variety of analytical techniques. This work required preparing herself for not only the physical challenges of living and working at sea, but also the adversities she would face as someone who was sailing alone with no other lab mates.

Preparing for Life (& Work) Aquatic

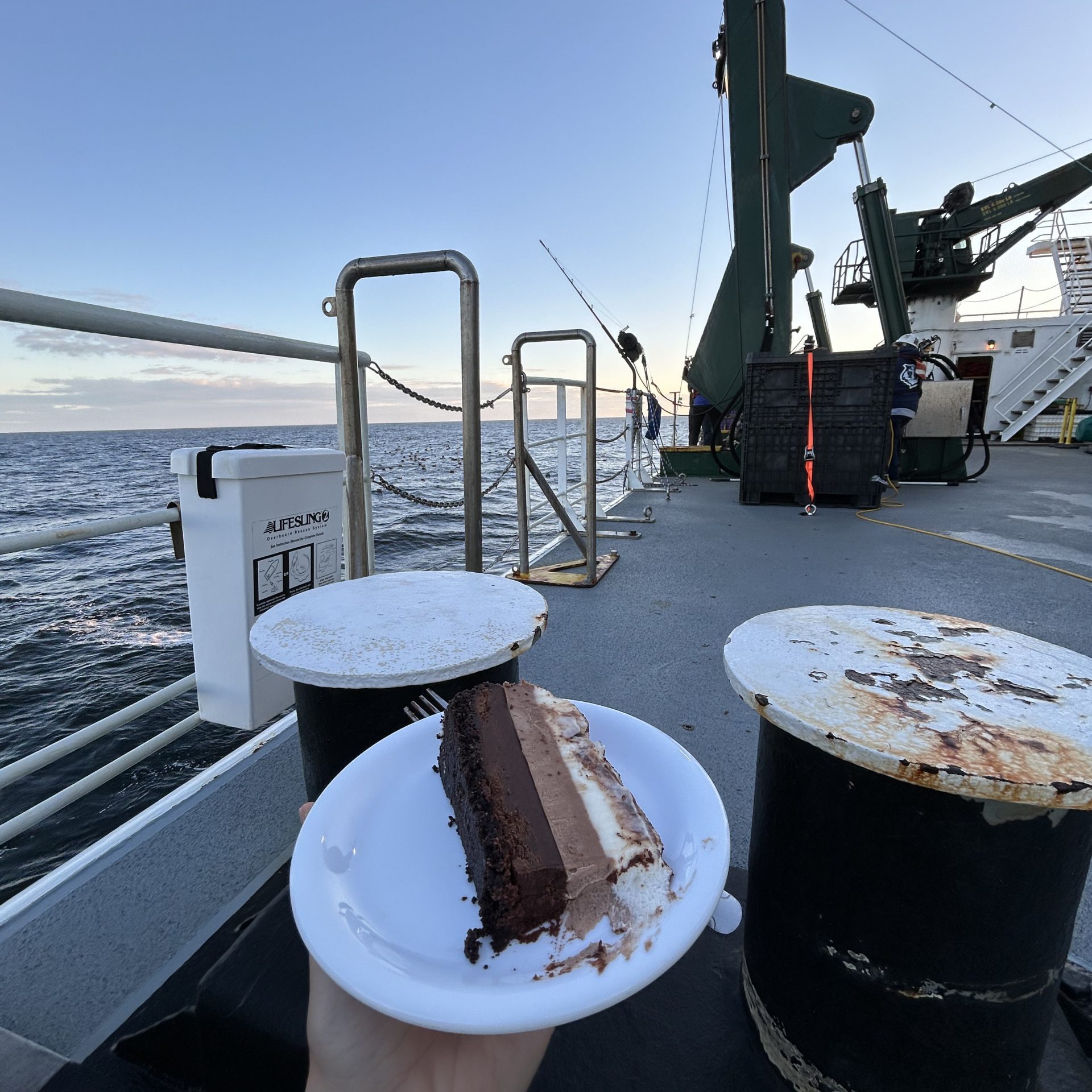

Preparing for a month at sea is a Virgo’s dream. The amount of forward thinking, planning (and contingency planning), preparing materials and organizing is enough to feed a Virgo soul for years. Chloe knew this is where she shined—meticulously preparing chemical kits for spiking her experiments, packing supplies like a world-champion tetris player, and creating flawless sample logs and cruise schedules. However, Chloe was very concerned about the mental, physical, social and technical challenges related to sailing solo for such a long research cruise, especially given her propensity for motion sickness. As a result, a major component of Chloe’s cruise preparation was gathering remedies for sea-sickness. On previous research cruises, Chloe had experienced violent sea sickness which essentially prohibited her from doing any work while at sea. She refused to be sick for the full month at sea on the R/V Kilo Moana and proactively assembled a mini anti-nausea pharmacy, including: standard over the counter motion sickness remedies (bonine, dramamine, pedialyte/electrolytes, ginger chews, acupressure wrist bands, and alka-seltzer tabs), more intense medications (prescription scopolamine patches and promethazine), and, in a last ditch attempt to combat the symptoms of living at sea, Preggie Pops, Seasickness Goggles, green apples, and a mini-portable fan. Chloe had never been more prepared to face her sea-sickness head on, and face it she did! After about 5 days of misery in her bunk, being tossed about by the 10-15 ft swell, she emerged from her cabin with sturdy sea-legs and the hunger of a sailor. An unanticipated, yet essential, component of her plan to stay healthy at sea was the incredible galley crew of the R/V Kilo Moana. The galley was not only a source of vital nourishment and sustenance for the crew, but also a place of bonding, story telling, and camaraderie. Each mealtime was embraced as a time for everyone to pause, come together, and fuel up for the next stages of their work at sea.

Adjusting to (and Thriving at) Living on the Ocean

Despite being an introvert, Chloe was nervous about being a lone-wolf for a whole month at sea. Her experience as a newcomer (both to ocean research and to the groups on board) came with many moments of discomfort as she became familiar with the nuanced and challenging work these groups have conducted at sea for years. Compounding this nervousness was the fact that she was sailing solo, while every other person on the ship was sailing with their advisors, or at least someone from their lab group. It is not typical for graduate students to sail alone for their first major cruise, though it can offer a fantastic opportunity to develop independence and resilience. In fact, Chloe’s shyness and hesitancy was quickly washed away by the 15 foot swell that the ship experienced as soon as it left the safety of the San Francisco bay. There are few things that encourage bonding and connection like working and living in a perpetually changing environment with 25 other human beings. Sleep deprived, hungry, sore, and without the comforts of home, family, and friends–everyone on the ship is pushed to the absolute limit of what they can physically, mentally and emotionally endure. After days of turbulent ocean conditions, waking up at 3am, working until 9pm, and keeping sleep-deprived tempers in check, the other people on the ship end up feeling more like an unconventional family than colleagues. Over the course of the 30 days at sea, Chloe no longer felt like she was sailing solo, but rather, ended up feeling like a lab member of every single group on board. By the end of the cruise, it was strangely sad to say good-bye to everyone and close such a brief, yet impactful chapter of her life.

The nature of working at sea requires people to readily adjust to the conditions of work. You have to adjust to the sea-state and plan ship operations around the weather, which often changes on an hourly basis. You have to adjust and adapt to your colleagues and ship mates, who come from all walks of life and experiences. You also have to adjust your science plans, because no matter how well prepared and planned out an experiment is, sometimes you have to skip your 72-hr time point because you can’t safely sample on the outer decks. Finally, and most importantly, we adjust ourselves.

The experience of going to sea offers a chance to look deeply inwards, whether in a professional or personal light. Professionally, Chloe had unlocked a new level of collaboration on the Kilo Moana. She applied new tools from her fellow scientists to her project, allowing her to holistically answer research questions from the perspectives of engineers, biologists, and physical oceanographers. Personally, Chloe connected with a stronger sense of resilience and persistence while at sea, especially in overcoming her sea-sickness. Since starting graduate school, she had the lofty goal of practicing yoga on a research vessel’s deck. Chloe was able to achieve this goal on the Kilo Moana, and not only did a handful of solo practices, but also led her very first group yoga flow. The sense of accomplishment in having strong enough sea-legs to practice yoga was a massive moment in overcoming and adjusting to obstacles for Chloe–she finally felt that she deserved and belonged in the marine realm. This was a massive turning point in Chloe’s oceanographic career, as her seasickness had always enforced her sense of imposter-syndrome and feelings of not belonging in oceanographic research settings.

The Come-Down, Back to Landlubbing

Chloe found the transition in going back to “normal life” to be much more challenging than she ever would have anticipated. After arriving in port on June 28th, the first thing she did was walk straight towards downtown San Francisco, barely slowing down for crosswalk signals to change. She felt compelled by her body to keep moving, especially after being confined to a 200 ft long ship for the past 30 days. Despite her body craving the movement, her mind was overloaded by the stimuli of the city–the sights, sounds, smells, crowds, noises and traffic of San Francisco had her nervous system firing on all cylinders after its month-long immersion in the ocean. In the brief moments that she stopped moving, her body constantly sent her reminders that she was accustomed to living on the ocean. “Dock rock” is a mariners' term for the apparent swaying of solid ground that certain people feel after disembarking after a lengthy sea voyage, and she was experiencing it only in moments of stillness (i.e. standing still or sitting). To combat her disorienting dock rock symptoms, she proceeded to walk around the city on a 15-mile trek, which not only reset her inner equilibrium, but also wrecked her legs and feet after barely moving for a month. Exhausted, but extremely satisfied with her adventure, she then met up with the rest of the science crew at a nearby brewery, where they spent the remainder of the evening celebrating, reminiscing about the last 30 days, and dreaming about their first moments back at home.

In the days following the cruise, everyone went their separate ways to return home (or in some cases, to Yosemite for backpacking, Santa Barbara for time to decompress, or to Alaska for the next cruise). For Chloe, this meant a 6 hour long flight back to Boston, followed by a 2 hour car drive back to her home near Cape Cod (with a quick pit stop at Taco Bell for a highly anticipated, well-deserved Crunchwrap Supreme). The idea of returning home had been one of her primary motivators over the past few weeks, yet the actual return home was less exciting than she imagined it to be. While it made her feel whole again to be reunited with her husband, cats, and New England home, it also felt like she had left a small part of herself with the Kilo Moana and the Pacific Ocean. She was acutely aware of how much she had gained from her time at sea: a new sense of resilience, a stronger sense of self and confidence, a deeper connection to her inner sense of adventure, and a reinvigorated excitement for her research and collaboration. Something that came as a surprise was the first morning that she woke up in her own bed, when she instantly felt a deep sense of longing for the Kilo Moana and the galley. She missed the obvious luxury of endless buffets of bacon, eggs benedict, biscuits and gravy, oatmeal, berries, muffins, fried rice, etc, but it was also more than that. She missed those bleary-eyed, barely awake conversations where everyone tried not to complain about how little we slept, how loud the MOC-NESS (Multiple Opening/Closing Net and Environmental Sensing System) was the night before, and how many salps we were finding in our water samples (not to hate on salps, but they eat everything, including the phytoplankton of interest). She missed the almost never-ending days of working on the ocean, where time seemed to cease to exist, and all that mattered was the sea-state and science plan for the day. It’s a type of simplicity and freedom that Chloe came to love dearly, and is trying to hold on as she returns to the hustle and bustle of her “normal” landlubbing life.