In June 2019, a crop of fresh-faced first-year MIT-WHOI Joint Program students boarded the SSV Corwith Cramer, a 134-foot sailing vessel, for an orientation cruise. The sun shone brightly on Vineyard Sound, and seagulls’ cries mixed with our animated chatter as we familiarized ourselves with the ship that would be our home for the next ten days. While the trip was nominally an educational opportunity, most of us were primarily looking forward to bonding with our new classmates and colleagues. And bond we did. As soon as we left the protective womb of the Sound and entered the open ocean, we discovered that there are few things that bring a group of strangers closer more quickly than getting seasick all at once. Almost all of my fellow sailors, many of whom are now close friends, experienced intense nausea at the very least. Some were glued to the railing for a good portion of the cruise.

On the Cramer, I learned about the different tiers of seasickness medication. There were the standard dramamine pills, which I had been aware of previously but never had to use myself before this trip. A more advanced remedy was scopolamine, which comes as a little patch you stick behind your ear and was promoted as a truth serum in the early 20th century. The final tier of seasickness medication on offer, according to the ship’s medic, “stops you from throwing up but doesn’t make you feel any better.” I unfortunately cannot recall the name of this medication, and neither can my friend who took it during that orientation cruise (“No, I was pretty out of it,” they responded when I asked.)

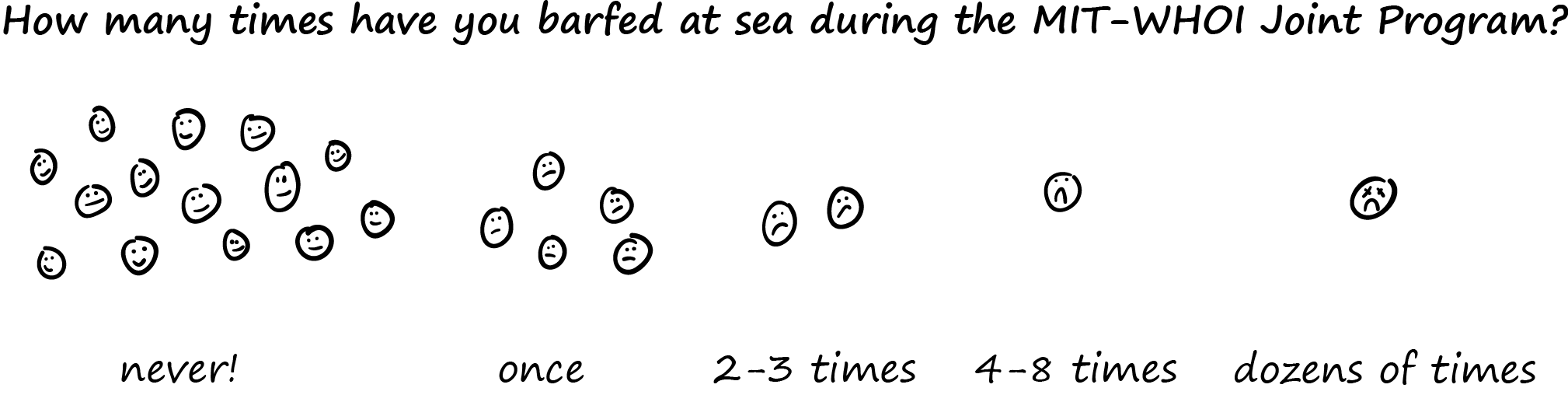

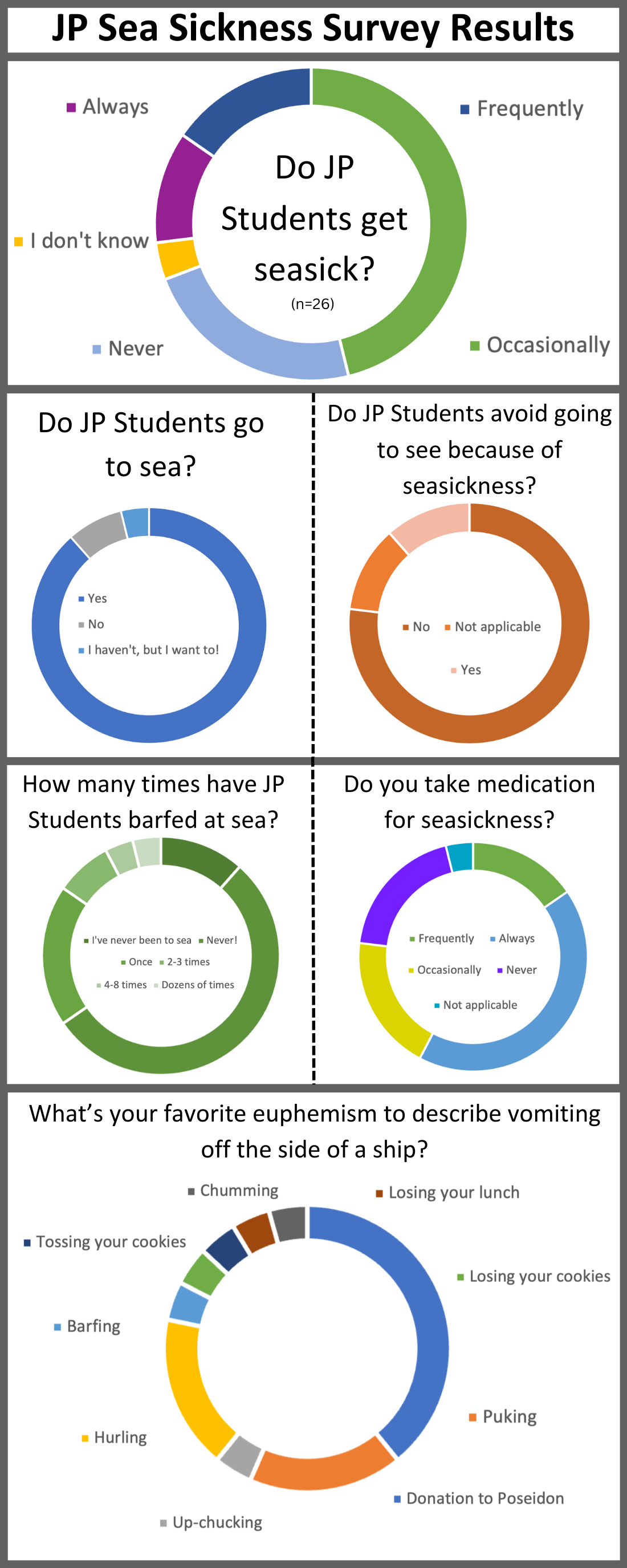

Although we have chosen a career that often brings us to sea, most oceanographers deal with some level of seasickness. In a Through the Porthole survey of current Joint Program students, about 75% of respondents said that they get seasick at least occasionally. About 35% percent of respondents have thrown up at sea at least once during their time in the Joint Program. Family and friends on shore may receive stunning photos of sunsets and videos of dolphins joyfully bow-riding along the hull of a research vessel, and while these are real and wonderful parts of going to sea, they conceal a less glamorous side of sea-going research. Those who have been to sea for research, which includes about 90% of our survey respondents, know to pack their bags with little bottles of dramamine pills and generous quantities of ginger chews and saltine crackers.

That said, seasickness does not affect everyone equally. There is a wide range of propensities for queasiness (and more) at sea, from those who are totally unphased to those who turn green while still docked. I spoke to a student who falls into the latter category, fellow TTP staff member and Chemical Oceanography student Chloe Dean. “I literally get carsick, so I don’t know why I thought oceanography was a good idea,” she told me. Nevertheless, Chloe has devoted much of her Ph.D. to sea-going research and has spent the past few years figuring out what works for her and what doesn’t when it comes to dealing with puking on boats.

Chloe’s first experience at sea came during a summer Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) at the University of California-Santa Barbara, when she went out with her lab group on a little boat to a kelp forest. “It was beautiful – we saw dolphins and this amazing kelp forest – but I was so sick. Other students were just sleeping on bean bags while we bounced on the waves and I wondered, ‘How do I get to a point where I can do that?’”

She didn’t get on a boat again until her first year in the Joint Program, when she participated in the annual student cruise on the RV Neil Armstrong, which typically takes place over a weekend in the fall and allows students to get a taste of what research at sea is like on a large working research vessel. On this particular cruise, the students and crew set sail in late November, leaving from Woods Hole and headed toward the shelf break to collect samples. Chloe had been eagerly anticipating the trip, as she had been put in charge of running flow cytometry and the Imaging FlowCytobot. Unfortunately for Chloe, however, November is typically windy in this region and the Armstrong drove headlong into a storm. “They ended up closing the decks down and we went off our intended transect,” she recalled. “I fell asleep in calm waters and woke up being tossed around in my bunk. I was not prepared for the boat to move the way it did.”

When a ship is experiencing “weather”, scientists’ best-laid plans often have to change at a moment’s notice. “It was so different than working in a lab on land,” Chloe said. “I know how to handle myself in a lab, and I sort of thought it would be like that but cooler.” Instead, she and many of the other students spent the majority of the cruise in their bunks, experiencing various levels of queasy misery. Even in these conditions, the kindness of her fellow students shone through: “My bunkmate was constantly checking on me, which was so nice of her. She found me stronger drugs, and even put the scopolamine patch on me herself.” Chloe’s bunkmate didn’t even complain that she was conspicuously hogging the bathroom during the trip. “I am the most violent puker; it sounds like my soul is coming out of me,” Chloe informed me.

Ever the determined scientist, Chloe managed to collect one deep water sample once the weather cleared up a bit. Unfortunately, when she presented her hard-won prize to her advisor after the cruise, she was informed that one such sample on its own was essentially useless. So it goes.

The worst part about getting extremely seasick, Chloe says, is the nagging worries about whether she deserves to be out there in the first place. “It hurt to see other people having to figure out how to do stuff that I knew how to but couldn’t because I was so sick,” she said. As she puts more and more cruise experience under her belt, she is learning how to make her time at sea more productive and less vomit-y. This includes packing better anti-nausea medication, as well as optimizing her work environment so that she can continue collecting samples even when in the throes of seasickness. “On my most recent cruise, I was finally working outside and could comfortably puke where I was working and still get my sampling done,” Chloe told me.

Chloe says that staying conscious of how special and unique the experience of doing research at sea is, and remembering to not compare herself to other people, helps keep her morale up. She told me a story about a cruise she went on recently near Martha's Vineyard. The ship’s steward had noticed how sick she’d been and offered up his secret stash of fruit popsicles. “I was laying out on deck on these buoys and sitting in the sun, eating my popsicle, and just thought ‘Wow, look where I am right now.’ Those moments happen even if you’re super miserable from the rocking of the boat.” No matter how sick she gets on the ship, Chloe said that the good memories tend to stick longer than the bad ones. “When I get back on land and a couple of days have gone by, all I remember are the dolphins and the flying fish, or seeing snowfall on the deck of the ship. Those moments make it worth it, sometimes even more than the science itself.”

Read more of Through the Porthole Issue #11

Learn more about Through the Porthole

Learn more about the MIT-WHOI Joint Program