“What do you want to be when you grow up?” We’re asked this question from the time we start kindergarten up until we graduate college. Then we’re supposed to have it all figured out, as though the passions that drive us when we’re 20 are the end of the road. But maybe you start a career and realize it’s not for you. Perhaps you struggled in classes and thought that meant you weren’t cut out for a certain type of job. Or it could be that you simply needed to experience life a bit more to discover what truly spoke to you.

For Erica Herrera, she had always had a passion for the environment; however, she didn’t realize it was her calling until she was 28 years old, working at a ski shop and cafe in Colorado. She had been reading a book called “Beyond Words - What Animals Think and Feel” by Carl Safina, which has a section on nuclear testing and the impact it has had on whale species.

“I started ugly crying in my room at 9 AM and I just felt like, what am I doing? I can’t just be here working at a ski shop while all these atrocities are happening. I just felt really compelled to do something. But then I was like, what can I do? Who’s going to listen to a [service worker] from Colorado?”

Deciding to go to graduate school at age 28 is not as common as waiting for a year or two after getting a bachelor’s degree, but Erica’s experiences between graduating high school and ending up in Colorado were all essential steps in her final decision to pursue an advanced degree. It started in the transition between the rigorous structure of high school to the self-driven model of college. When Erica started her undergraduate degree in agricultural and animal science at the University of Texas El Paso, she wanted to be a veterinarian. However, she soon began struggling to keep her grades up.

“I had undiagnosed autism. I remember struggling a lot in my classes and at the time I kind of wrote that off as like, oh, whatever, I’m too into partying. But really, I think the whole new way of doing things [in college] threw me off. I wasn’t used to being bad at things, so I threw myself into partying to cope with that.”

As a result, Erica didn’t have the grades to become a vet. Instead, she began to work at a veterinary clinic as a technician. Unfortunately, the work environment was toxic and she began to spiral.

“I was having a quarter life crisis of like, what was I going to do?”

Her partner at the time asked her what she wanted to do. She replied that she wanted to be outside and have adventures, but she didn’t have anyone to do it with.

“He said, ‘well, why don’t you just go by yourself?’ It sounds really simple, but at the time it was a revelation.”

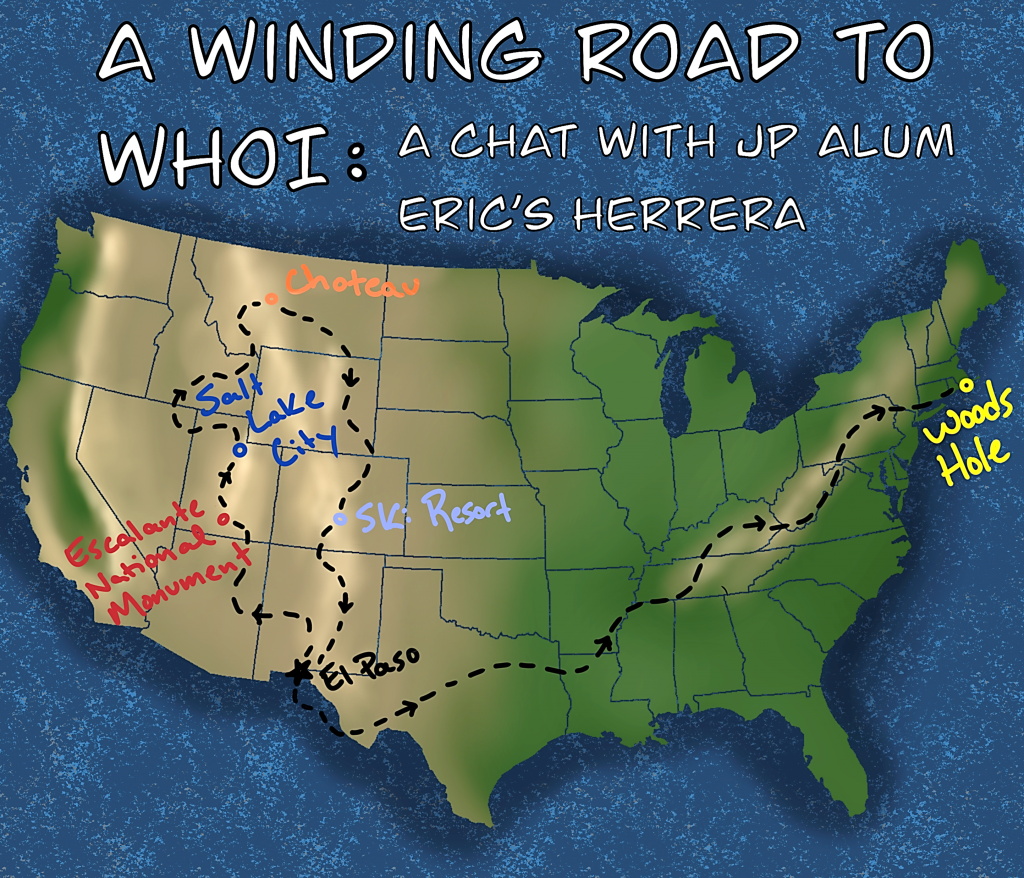

So she did! Through a website called coolworks, Erica managed to find an out-of-the-box job posting that could fuel her travels. The first adventure was to the Escalante National Monument, where she joined a chainsaw restoration crew that was working to rid the park of an invasive tree species.

“I set off to the wilds of Utah. It was a huge culture shock, but it was also an amazing experience. So after that, I just kept seeking more.”

Working with the conservation corp in Utah inspired her to search out other opportunities. When she mentioned that she enjoyed skiing, they directed her towards Salt Lake City in Utah. There, Erica learned to snowboard while working in a coffee shop. When the winter season came to an end, she decided to look up guest ranches in Montana, as she had always been a horse girl at heart. One ranch in particular was focused on sustainability and education, which aligned with Erica’s love of the Earth. As a result, she ended up traveling to Choteau, Montana, to work for the Nature Conservancy. During her stay at the ranch, she taught visitors about nature and sustainability. When the season ended, she knew what she had to do. Looking for a winter job, she located a ski town in Colorado that needed workers. There she worked at a ski shop and a bookstore, which she helped get certified by the Global Council of Sustainable Tourism by implementing sustainable practices like composting and product swaps. With each step on her journey, she began to fall deeper in love with helping the environment.

When Erica decided that she wanted to apply for graduate programs, she knew she had to make some changes in her approach to academics.

“The first time around I did manage to develop skills, like how to study. And then, when I went back [to college], I was obviously more of an adult. I had supervisory experience and more life experience to be able to say, okay, this is what I need to do.”

For example, Erica had always struggled in quantitative classes, failing organic chemistry the first time around. But six months before classes began, she started going on YouTube and watching math tutorials to help prepare her for the upcoming semester.

“I remember the first day of classes I was like, oh my god, this is a nightmare! What am I doing? But I didn’t give up, because I knew I needed it to get where I wanted to go.”

In order to get into a graduate program that focused on environmental issues, Erica essentially did a second bachelor’s degree in chemistry. During her second undergraduate degree, she applied for the WHOI Summer Student Fellowship (SSF), which allowed her to experience research in Dr. Julie Huber’s lab. Working under a postdoctoral investigator (a recently graduated PhD student), named Dr. Sarah Hu, Erica investigated microbial grazing occurring around hydrothermal vents. This was the first time anyone had observed grazing occurring in this environment.

“The whole SSF experience was a wild ride where you’re fire-hosed with information and plagued by the feeling of ‘am I doing this right?’ So when something [cool] comes out of it, and something completely novel like that, I was excited. It was probably one of the reasons I wanted to continue in oceanography.”

When it finally came time to apply to graduate programs, Erica was accepted to the programs at both WHOI and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. When asked why she chose WHOI, Erica laughed and said,

“I never really wanted to live in San Diego and the stipend was better at WHOI. As a poor person, that’s a huge motivating factor. Plus, the lab members seemed cool.”

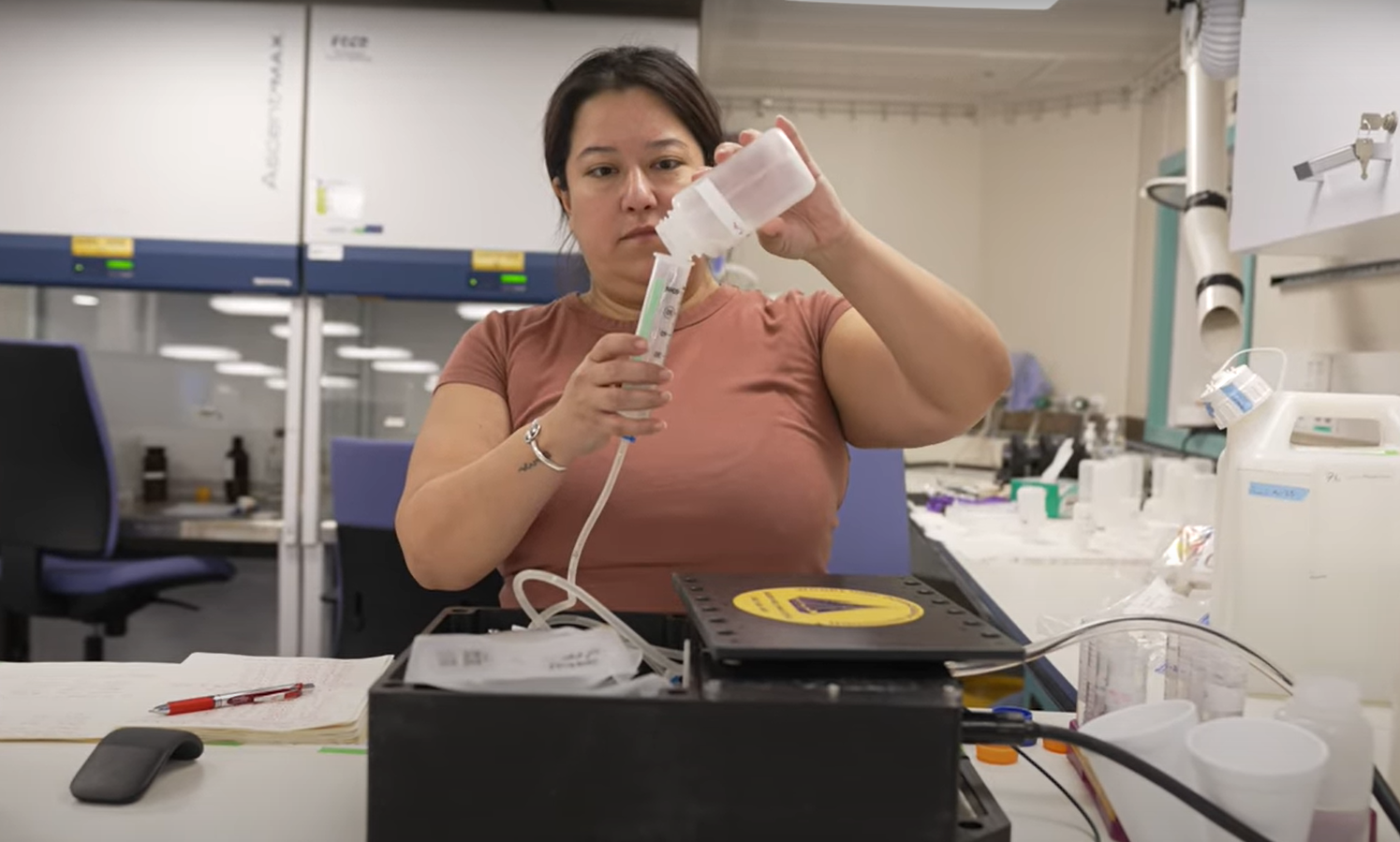

She joined Dr. Colleen Hansel’s lab in 2020 and worked on the geochemistry impacting hydrothermal vent mineralogy, getting her Master’s degree in January 2024. She is now looking for jobs that will help her guide individuals, businesses, or policy towards a more environmentally-conscious future.

“Since reading that book about the whales and nuclear testing, I wouldn’t say my motivation has changed. I think what motivates a lot of us is that we’re desecrating the planet. We need to find a new path. We’re not totally sure what that path is, but we need to get there somehow. And I feel like I’ve always been pretty okay with that. So I’m not entirely sure what it looks like now, but I know I’m not going to take a job unless it aligns with that path. I’m excited about what’s next, even though I’m not totally sure what it is yet.”