- Leighton Rolley makes sure the winch re-spools the cable properly, after repairs to the level winder. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Marshall Swartz keeps an eye on the wuzzle as the winch unspools. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

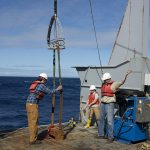

- A team prepares a weight to go over the stern of R/V Thomas G. Thompson to test repairs to the winch. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Marshall Swartz (foreground) and Leighton Rolley examine a wuzzle on the winch drum caused by a faulty level winder, a mechanism that keeps the cable properly positioned on the drum while the winch is spooling or unspooling. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

There is a saying in oceanography, “Don’t put anything in the water you can’t afford to lose.” The day someone first decided to study the ocean was the day he or she first lost an instrument in it. The day after—once that poor soul had fixed what went wrong the first time—was the day ocean science truly began.

To understand and accept that risk, to have the ship, the equipment, and the people all in place and ready and yet to be denied the opportunity to try is harsh. But it’s not uncommon, because a last-minute addition to every ship’s manifest is Murphy, and his law can trump the command of even the best captain.

Three nights ago, Nereus and the vehicle’s depressor went over the side without a hitch, and the extra deckhands and late watch-standers drifted off to get some sleep. Moments later, with the vehicle at less than 200 meters beneath the surface, an alarm sounded on the winch control in Mission Control. A quick radio call to the spotter on deck told us that the level arm, which keeps the cable properly aligned with the winch drum, was not moving.

The Nereus team stopped the winch, but the vehicle and depressor continued down under the pull of the vehicle’s descent weights. When both reached the limit of the cable that had already been paid out, they began to jerk and bounce in the water as we rose and fell on the waves. After a few minutes, Nereus’ float pack separated from the main body of the depressor, as it is designed to do, and Nereus continued down. Somewhere along the way, the optical fiber in the float pack separated.

When Nereus sensed that its link to Mission Control had been severed, it began a countdown to release the descent weights and return to the surface. The delay is programmed in so that we can move the ship to a safe distance. One hour later, we caught sight of the vehicle’s strobe light across a moonlit ocean and began the recovery process.

Nereus always looks impressive coming out of the water. It exudes a sense of refined purpose. But that night it had been robbed of its purpose and it settled into its cradle like a racehorse taken for a leisurely trot halfway around the track and then stabled. Later in the night, the wind picked up and for the next two days we were idled while a storm spun far to the west of us.

The key is to limit the damage Murphy can do by anticipating his every move and keep him confined as much as possible. That’s why we check and double-check lines and fittings. We run through pre- and post-dive checklists. We constantly look around us and above us.

But some things escape even the most watchful eye, and no one would leave the dock if they had an infinite to-do list and unlimited time. At some point you have to trust that as much has been checked off that can be and lift your lines. You take the leap of faith, you think Murphy’s safely behind you, then you turn a corner, and there he is.

The good thing about being on many expeditions like this is that it is invariably staffed with people who can disassemble, reassemble, fashion, modify, or improve just about anything. It’s a necessity out here, where a round-trip to the hardware store is measured in days or weeks. The autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry once flooded while deployed and caught fire, destroying most of its internal electronics. Engineers took it apart, cleaned up what they could and used spare parts on board to rebuild it. At sea. In four days.

So Murphy made an appearance and enacted his law on this trip. Fine. Now he can watch while we put things right and get back in the water.