I am going to tell you a story—a love story. We are old friends, the kind who have known one another since childhood. Back then, we met only once per year during summer holidays, enough to forge a friendship that has lasted since then.

I have to admit that as I grew up and my interests turned around, our ties become looser and looser until few years ago, when my life made one of it periodic shifts. One of the implications of being a scientist is that you get to travel a lot and change the place you call home quite frequently. After my Ph.D., I moved to the U.S. to work at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, across the street from WHOI, where we reunited, as he was part of the research group I joined.

Although we never worked together then, we spent four summers and three winters side by side, time that allowed us to better know each other. We become close friends. As usually happens, I didn’t realize how much I enjoyed his company until it was too late. A year ago I had to move again, as I was starting a new position at Brown University. Although we are not so far away from each other, I missed our everyday encounters right away.

But who knows if destiny exists because even though now we seldom see each other, we interact indirectly during my work at Brown. This has allowed me to realize that he is full of surprises, and my enthusiasm about him and all his secrets has grown lately. However, it has been during this cruise that I finally have fallen in love with the Ocean.

This cruise is full of first-timers, but I beat them all. For me, this has been the first time I enrolled on a ship, slept on a ship, lost sight of land, and saw only water day after day for weeks. I had to learn how to defeat seasickness while working hard at the same time. I became familiar with the ship’s murmurs and terminology, which is English at Foreign Language level 10000. I have loved it all. But what makes a trip like this so unique is the people on it, from crewmembers to my already familiar colleges. An oceanographic cruise is only possible because of a huge team effort, and it has been great to become part of it.

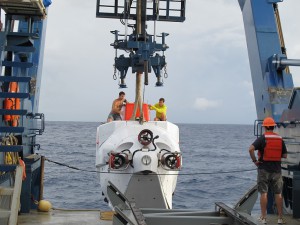

Microbiologist KT Scott, pilot Bob Waters, and postdoctoral researcher Nuria Fernandez Gonzalez in Alvin

Being out here has been an incredible opportunity to better know the Ocean. And for that, there is nothing like a dive in Alvin. The inside of the sphere is quite similar to the Apollo spacecraft you can see in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, a tiny space full of buttons but without seats.

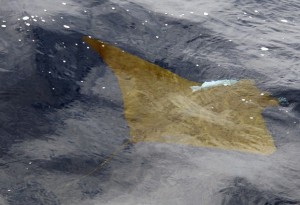

A ride in Alvin is actually quite peaceful, and the views are spectacular. At first, what shocked me most was how full of life the Ocean is regardless of what I have read about him being mostly a blue dessert. The dive started with an unexpected visit from a manta ray that hung out with us for a little bit. It was impressive to see her flying around the sub over and over with curiosity.

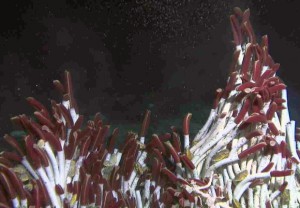

During the descent, the lights from bioluminescent organisms accompanied us all the way down except at the depths of the oxygen minimum zone, where we were completely surrounded by the dark. But even that cannot prepare you for the explosion of diversity in the vents. I felt like we were entering a subaquatic garden where the dominants colors were white, red and yellow. Later that day, once I was back on Atlantis, I looked at the Ocean with a new awareness of his enormousness and importance for the whole planet. In that very same moment I knew that this was my first but not last cruise, as now my heart has been stolen by the deep blue sea.