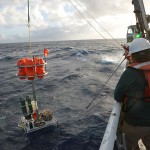

- The hadal lander returns to the surface with water samples from 6,000 meters and an unexpected surprise—a mud core inside one of the lander’s legs. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Scripps Institution of Oceanography microbiologist Doug Bartlett collects a water sample from the hadal lander. Bartlett will incubate microbes in the seawater under pressure to learn what types are specifically adapted to life at hadal depths. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The mud sample brought to the surface in the hadal lander’s leg proved to be an unexpected boon for Beatrice Lecroq from JAMSTEC, who searched the sediment grains for tiny shelled organisms known as foraminifera. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

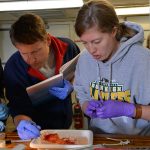

- Santiago Herrera from WHOI (left) and Kirstin Meyer from the University of Oregon gather tissue samples from the large shrimp brought up in the fish trap while University of Hawaii biologist Jeff Drazen attempts to identify the species. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- WHOI biologist and cruise chief scientist Tim Shank, who has described three species of hydrothermal vent shrimp during his career, spends some time studying the hadal shrimp. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Nereus enters the water at the start of a successful dive to 6,000 meters at the southern end of the Kermadec Trench. (Video still image by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

We’re a little more than halfway through the cruise and it’s time for an update on where we are and where things stand.

Right now we’re at the southern end of the Kermadec Trench facing a tight schedule of dives and deployments. We completed a successful dive to 6,000 meters tonight, but we’ve had mechanical and technical problems that have delayed or cancelled some of our operations and forced a port call in Auckland for repairs. Everyone is still hopeful we can gather the data and samples we need to form a picture of life in the trench.

We’ll work our way north deploying Nereus when possible and the landers and fish trap at 1,000-meter increments up to 10,000 meters depth, then turn and make as many deployments as possible up the western flank of the trench. The depth changes quickly with distance on the western side, so this will maximize our remaining time before we have to turn back and steam for Samoa.

One of the critical depths for the biologists to observe and sample is around 7,000 meters, which is where we dropped one lander and the fish trap tonight (May 2). Once we finish this dive, we will go back to pick them up and then deploy Nereus as soon as its batteries are recharged and everything else is ready.

Seven thousand meters is important because that is where species specific to this trench would begin to appear. The depth seems to mark a boundary that prevents migration among the world’s hadal habitats. Most other fish disappear just above 7,000 meters and snailfish (Liparidae spp.) become the dominant species seen at the landers.

A surprising shrimp

But we’re after more than just the scavengers, which are the most common visitors to the baited fish trap and landers. That’s where the camera and sampling transects run by Nereus will be important—filling in gaps left by the selective view of these two instruments. Everyone was, however, pleasantly surprised today to find a large shrimp in the fish trap. These are predators that feed on amphipods and have been photographed throughout the hadal and abyssal Pacific by Alan Jamieson and others as deep as 7,703 meters. In fact, until just a few years ago, the general consensus was that the entire order (Decapoda ) that includes shrimp, crabs, crayfish, and lobsters did not exist in the hadal zone.

This shrimp came up from a little over 6,000 meters and, while probably not the first to be captured, is certainly one of the largest. It’s also something that Jamieson has been chasing for the past seven years, but has been unable to capture because they seem to have very acute sensory organs that have enabled them to avoid almost every type of trawl, net, or trap. “They’re covered in sensors,” said Jamieson. “It’s almost like they were made to avoid being captured.”

There were no fish in the trap this time, so all of the usual bustle that surrounds sampling the large animals was focused on the one shrimp—though at nearly 20 centimeters, the name is not entirely appropriate. The gut contents went to Doug Bartlett, our microbiologist. Kirstin Meyer took gonad samples and fixed them for later study. Santiago Herrera preserved segments of the animal’s swimming legs and tail muscle for genetic analysis later in Tim Shank’s lab. Paul Yancey took samples of hemolymph—the blood-like fluid in spiders and crustaceans—as well as muscle samples so he can look at adaptations to pressure. Jeff Drazen and Dan Mayer both got frozen muscle samples so they can look at cellular biomarkers and enzymes that tell something about the shrimp’s metabolism and feeding habits.

All of those came from one side of the animal so that the remaining carcass, with one intact side, could go to the museum at the National Institute for Water and Atmospheric Research in New Zealand. Tom Linley also photographed the intact side and stitched the high-definition images into a 3-dimensional reconstruction he is developing as a way to allow taxonomic studies without a live specimen.

Drazen also took a stab at identification, but as an admitted “fish guy” who is more interested in ecological questions surrounding the animal and its hadal neighbors, he eventually found himself at a dead end. He was, however, able to reasonably conclude that it was a member of the genus Benthesicymnus. Final taxonomic identification will be left to “shrimp guys” who know the details of animals like these by heart and who will also have the only other similar specimen to compare against. “You really have to know what to look for,” said Drazen. “There are characteristics in there that I can’t see.”

The same goes for an eel pout we caught earlier in the trip. Although, because it’s a fish, Drazen is more confident in thinking that it will prove to be a new species. But the real goal is to understand the role that any species we find—in images or in the fish trap—plays in the hadal ecosystem. If it is a predator, what does it eat and how does it find prey? If it is a scavenger, how much food is available to it? How do animals mate and migrate? What range of conditions does each prefer or can each tolerate? These are questions we’re hoping to place in the target in the time we have remaining out here in the Kermadec Trench.