- During its short career in ocean exploration, Nereus provided unmatched capabilities for exploring and sampling the hadal zone in a systematic way. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Nereus provided some of the most extensive and comprehensive views of the seafloor during its dives, enabling scientists to observe and sample individual animals as deep as 10,000 meters beneath the surface. Here, the vehicle’s slurpgun homes in on a brittlestar.(Video still courtesy of the HADES program, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

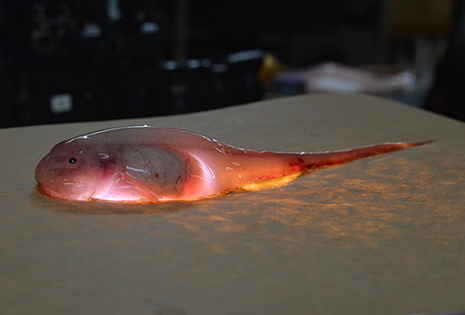

- Scientists placed this snailfish on a lightbox to highlight the fact that its body is translucent. The big, dark blob in the middle of the fish is its liver. Before this cruise to the Kermadec Trench, only about 10 snailfish, the deepest known fish in the ocean, existed in collections around the world. Now there will be 45 more. (Photo by Jeff Reed, Montana State University)

- Video from the stationary landers also provided unseen views of seafloor fauna, including the first recording of a super-giant amphipod swimming. (Video still courtesy of Alan Jamieson, Aberdeen University)

- New processes involving life in the trenches were also identified or hinted at in samples collected during the cruise. This piece of pumice found at 8,000 meters carried algae and animals from the sea surface attached, making it a potential path for food to move from surface waters to the deep ocean. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- As exciting as hadal research can be, paperwork remains a part of everyday life. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- In addition to the many scientific firsts from the cruise, HADES also successfully broadcast images live online from 10,000 meters via a satellite telepresence unit provided by the University of Rhode Island’s Inner Space Center. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The last piece of equipment came on board in the early evening of May 14—the abyssal lander. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

This wasn’t how the cruise was supposed to end, but then there is no way to expect anything of the ocean other than what it will give you. Or take from you.

Nereus is gone, taking with it the only vehicle available to the international ocean science community capable of reaching full-ocean depth. We also lost many of our planned dives to technical problems, bad weather, and bad luck. Time on vessels like the Thomas G. Thompson is not cheap and does not come easily, which means that making up for these lost opportunities will be difficult—maybe even impossible if there is no replacement for Nereus in the near future.

But to dwell on the things we lost or missed out on collecting would be to dismiss the incredible wealth of samples and knowledge and tantalizing hints that came back from the Kermadec Trench over the past five weeks.

Over the course of four complete dives, Nereus visited places that have never been seen or surveyed before and recorded more than 24 hours of ultra-high-definition video, including two video transects of the seafloor at 10,000 meters. Live and recorded imagery from the vehicle revealed a diversity of habitats and seafloor types that had not been previously documented, greatly increasing the potential biological diversity of hadal orgnaisms. Nereus also collected a wealth of rare hadal animals, including an organism resembling an octocoral that has so far defied description or categorization.

The abyssal and hadal landers also revealed a wide range of bottom types and topography at the same time that they were recording the diversity of fish, amphipod, and other species attracted to them. A total of nearly 57 hours of video and 14,000 still images provided evidence of new behaviors among hadal species, from benthipelagic swimming among snailfish to suction feeding by cusk eels. The hadal lander also recorded the first known video of a live super-giant amphipod and captured details of its swimming and feeding behavior.

These images were supplemented by the physical specimens that arrived on the surface with the fish traps that, among other things, brought back more than three times the number of snailfish—the deepest dwelling fish in the ocean—than had been previously collected. The traps also brought up a super-giant amphipod and other rare animals, as well as a wide range of sizes, ages, and locations for grenadiers and other deep-ocean fish. These samples have provided new insights into the adaptations that life has made to conditions in the deep ocean, including the first full-depth profile of osmolytes—the substances in cells that allow proteins to fold correctly under high pressure.

Images, specimens, samples, and data will be shared among the researchers on the ship and around the world. Information from these will be compared to existing data and eventually combined with what we learn on future HADES expeditions to more of Earth’s deep-ocean trenches.

Perhaps the most significant finding of the past 40 days has been to confirm something that has been at the heart of the HADES program from the start—that the hadal ecosystem of the deep trenches is vastly more complex and varied than anyone imagined. At the same time, however, we showed that the deep ocean is in many ways no more unique than any other ecosystem on the planet. It is not alien, nor are its inhabitants fantastic monsters. Rather, it is simply another place on this planet where life has managed to take hold despite some challenging conditions. That is not to say we should dismiss the hadal regions entirely. Rather, we should acknowledge that our perception of the deep ocean as some mysterious, otherworldly place arises solely from our ignorance of it and of life’s ability to survive and thrive in some truly amazing places.

The hadal region is not beyond our grasp—in fact, the occasional piece of trash we found underscores the fact that humans have been reaching into the deep ocean long before we arrived. It is currently beyond our understanding because we lack the basic knowledge of the processes that govern the deep ocean and that link the hadal world to our own. Lacking this knowledge, we walk the face of the planet not knowing how our actions might impact this special place or how the deep ocean plays a role in our everyday life, and just how special life everywhere in that, given the opportunity and resources, it can inhabit even the deepest, darkest corner of Earth.

By the time you read this, we will probably be in port in Apia, Samoa. The scientists of the HADES program and crew of R/V Thomas G. Thompson thank you for reading and following along during the cruise and we look forward to sharing forthcoming expeditions to explore the hadal depths of Earth’s ocean.