For the past several days, the focus of activity on board the Neil Armstrong has been on the OSNAP project. OSNAP stands for Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program, and is an international effort to measure all the currents moving northward across 60N latitude, as well as the heat those currents carry. As described in earlier posts, we are out here on Armstrong to replace four deep-sea moorings that are part of the huge OSNAP “observing system” that stretches from Labrador to Scotland.

At the same time as we undertake this new responsibility in OSNAP, another of our contributions to this massive program is coming to a close—or at least the field phase is. Starting in 2014 and continuing through 2017, we launched about 120 buoys to drift with currents far below the sea surface. In fact, these floats were set up to follow the deep flows just above the sea bottom. This is where the coldest limbs of the Great Ocean Conveyor—the system of currents that carries heat northward in the Atlantic Ocean (by transporting warm water northward and cold water southward)—are located. These floats are tracked underwater using sound, so to keep track of where they have been traveling while underwater, in 2014, we installed 13 acoustic beacons that make a special sound, only recognizable to the floats, every day.

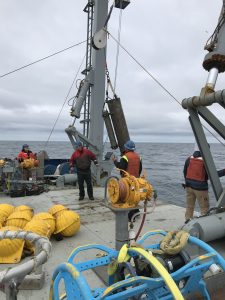

So at this point, all the floats have been deployed, and the last of them will come back to the sea surface to report their data by the end of this year. With their job complete and batteries running low, the acoustic beacons are being gradually picked up on various research cruises this summer, including the one we are on right now.

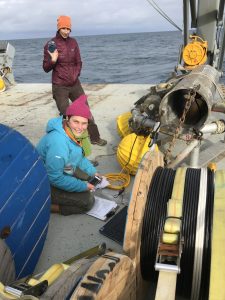

This past Monday, we recovered the mooring that was holding acoustic beacon #4 (out of a total of 13). As soon as the beacon was back on deck, Heather connected it to a laptop in order to check its internal clock and then power it down.

Heather checking the internal clock of the acoustic beacon against the ship’s clock, and powering the instrument down after its four year mission at sea.

Two other beacons have already been picked up by our German and U.K. OSNAP colleagues, and five more will again see the light of day later this summer and fall. Several of the beacons will not be recovered at all. They don’t have any data in them, and some are located so far off the track of any upcoming research cruise that it turns out not to be financially worthwhile to recover them. It would take more than a week of ship time, and one beacon costs about the same as one day of time on a research vessel. Nearly all the components are at least eventually, bio-degradable, so by leaving them behind, we hope not to be contributing to much to marine pollution.

Just because the float data collection is over doesn’t mean the whole float project is over—far from it! In fact, some might say it is just beginning. Now comes the task of reconstructing each float trajectory to find out where it drifted for the two years it was down deep in the darkness. Once that is finished, the even more exciting and interesting step begins—trying to figure out what it all means. Our goal will be to interpret the float trajectories based on what we already think we know about the deep currents, and (hopefully) discover some currents that have never been seen before. This is the essence of why we do what we do—to describe how the ocean works so that we can predict how it will change in a future that will undoubtedly see major climate changes that will impact both the atmosphere and ocean.

Amy, many of us Warner related relatives, related to your friend Duane, got this wonderful link to your work! It is so exciting to read and to know of the good work that you all our doing! Duane told us he is picking up a new wind surfing activity so I did tell him about the big wind surfing place out here in Oregon on the Columbia River Gorge near the Old Celilo Falls fishing grounds. The sad part about the area was that the falls used by our native ancestors including our Uncles and some brave Aunts was flooded out to put in a big dam. A few years back Life Magazine or one of the major magazines had some special pictures done showing that most of the falls area is still in place under the water. The wind surfing started many years after the dam was built, actually within the past 15-20 yrs. Large groups of surfers meet at various times and when the wind is good they try to make it from the Oregon side of the river to the Washington side of the river. Can see that you and Duane have a great love and appreciation of water! Thank you for your blog and sharing your wonderful work! Roxanne Woodruff