The other starboard. In theory, the way that we bring NUI back to the ship sounds straightforward. In practice there can be wrinkles. NUI was told to come up to 2 meters (7 feet) depth at a range of 50 meters (160 feet) from the center of the ship on our starboard side where the Captain has prepared a nice pool of open water for it to surface. Instead, it came up at a range of 50 meters from the center of the ship on our port side under ice! (photo by Chris German, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Some days I just really truly absolutely positively love my job.

NUI Dive 14 began with alarms ringing at stupid-o’clock on Tuesday in cabins all along the length of the NUI team’s corridor to turn us out, ready to start work at 4:00 a.m. Based on past performance, we had estimated that we needed 3.5 hours to prepare the vehicle to be ready for the crew to help us launch at 8:00 a.m. So, with half an hour for breakfast at 7:30, that meant a 4:00 start.

So we all showed up, got to work, and were ready by 5:00. I think the team just wanted to prove to me that I didn’t need to insist they get up that early ever again. But it WAS nice to be ready ahead of schedule for a change—and the ship’s officers appreciated how hard we were trying to make things work.

As it was, the prior operations on the ship, took place about five miles from where we were launching and had run late. There was also thicker ice than expected that we had to break through to get to our launch site. At 9:30, we were at the launch site, by 10:00 we had the right size and shape hole in the ice set up, and by 10:45 NUI was in the water and headed to the seafloor. I could tell you that everything else after that went perfectly and you would be none the wiser. So lets leave it at that, OK?

In truth, there were some challenges to overcome. An important set of all the different ways that we navigate NUI at the seafloor didn’t “come to the party,” as we say, which delayed our transition from arriving at the seabed, which occurred around 11:45, to when we could finally start our science mission (not until 2:45 p.m.).

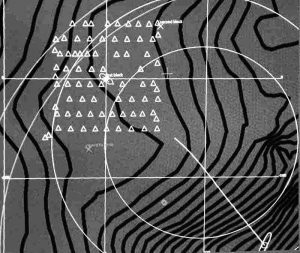

Happiness is a warm map. This is what the navigation file looked like at the end of the NUI Dive 14. Black lines show the contours near the summit of Karasik Seamount and the white triangles show updates of NUI’s position as it “mowed the lawn” from west to east then moving north 75 meters (250 feet) and continuing back from east to west to map the seafloor in high resolution. The white squares are 500m on a side, and the same area as the region mapped by NUI. The white line trailing to the bottom right shows the position of the ship as it was pushed southeast by an ice floe while NUI, by design, was able to carry on working right where we wanted. At the end of the survey we simply put NUI into park mode where it was, had the ship break ice back to where NUI was, and then sent the robot directions on how to come back up to the surface to meet us.

But then, finally, for one and a half glorious hours, NUI boldly set off and “mowed the lawn” as it mapped the seafloor, flying 50 meters (160 feet) above the bottom in about 600 meters (2,000 feet) of water and beneath a nearly 100 percent ice-covered Arctic Ocean.

It may not be a record for depth of an AUV dive in the Arctic, nor for the size and shape of the area mapped, but any parent who ever saw their child ride a bicycle for the first time without training wheels will be able to grasp how special this was for us and for NUI. Yes, it did look just like the kinds of patterns made by ABE, the first AUV designed specifically to fly near the seafloor that I ever worked with back in 2004, but that isn’t a bad thing. Quite the opposite. What it said to me is: “NUI is open for business!”

All too soon the survey was complete and light was fading, so it was time to plan an orderly retreat. First, we instructed the vehicle to do one final drive close to the seafloor at three meters (10 feet) off the bottom for 100 meters (330 feet) in preparation for our next dive when we hope to photo-mosaic the seabed in the area that we just mapped. And then it was time to find a nice hole in the ice, move the ship into it, and whistle our puppy to come home (via underwater acoustics).

By 5:30 p.m. we had the ship set up and by 6:30 the vehicle at 30 meters vertically and 100 meters horizontally from us. The last step was to instruct NUI to come in closer and up so that we could see its lights just beneath the open water on our starboard side. Casey, John, and I went outside to confirm we could see the lights, but we saw nothing. Then a call came from the bridge: They could see a lights shining through the ice over on the port side half way down the length of the ship, and about 50 meters (165 feet) out. NUI had come up on the other starboard.

Soon enough, we had established a wireless connection using the controller that works near the surface (NUI could be the world’s most expensive remote-controlled underwater toy) to drive the vehicle around the bow to the correct side of the ship and we brought NUI safely on board.

It had been a long day—more than 15 hours—and we still had the post-dive check to complete, but not before sharing a celebratory bottle of champagne (this ship has great shopping opportunities) and the dinner that the cooks had set to aside for us because we worked through meal time. By 9:00 p.m. everything was done and we could relax and breathe.

Next up is a quiet day for NUI: We’ll be working up the data from today’s dive and getting the cameras ready to photograph the seafloor on our next dive (pre-dive testing on Thursday, dive day on Friday). But it will hopefully be a busy day for me, with a deep-tow camera survey back at the deep vent site in the morning and then a CTD tow-yo to chase plumes from late afternoon to midnight. There’s never much time for rest with so much going on, but then again, it does make the days—even weeks—rush by. Soon it will be October 1, when two major changes are due.

But you’ll have to keep reading to learn about that.