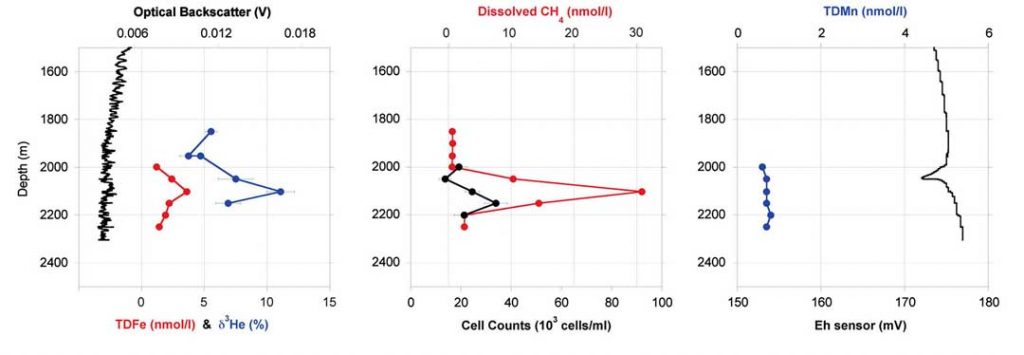

While the new data from this cruise are hot off the presses and the samples have yet to be analyzed, one of the plume signals we intercepted on Sunday had a curious combination of plume signals that we had previously seen during a 2009-2013 project studying hydrothermal venting on the equally ultra-slow spreading Mid-Cayman Rise in the western Caribbean. This figure shows all the different kinds of analyzes we conducted there on the physics, chemistry, and microbiology of the ocean associated with that hydrothermal plume. Out here, we have the in situ sensor data in-hand already for particles and redox anomalies, the latter using instruments provided by collaborators in the US and Japan (Hi Sharon! Hi Ko-ichi!). The next job has been started by two groups on the ship—Jill and Gunter, and Kevin and Laura—to measure hydrogen, methane, and ammonia concentrations. That will be followed on shore by work from Wolfgang Bach’s team to analyze trace metal content (Alex and Elmar are out here with us to make sure they collect the right samples) and a range of further microbiological analyses in Antje’s lab. But hopefully we don’t need to wait that long to learn more. Better still would be to fly right over, and photograph, the vent site.

After Friday’s fun, our cruise took a different direction over the weekend. Literally. We relocated over night to our deep hydrothermal vent exploration site and suddenly it was 3:15 a.m. Saturday morning and a phone was ringing in my cabin.

At first, I couldn’t even find the phone. Eventually I was able to locate it and the voice on the other end asked if I knew where my vent was. Fortunately, my cabin-mate Louis is a heavy sleeper. I confirmed the location and that I was awake and ready for our first vent-hunting station.

Our first tow-yo with the CTD did not go well. The drift of the ice pushed us south and east of a volcanic ridge that we are targeting, so we had to study an area away from the ridge summit and confirmed that it had no hydrothermal plume signals. Not an exciting result, but still useful—that meant there was no need to search the area any further.

Since we hadn’t used up all the time available to us until the next team were due to start work, we quickly relocated the ship closer to the west end of the ridge and did another CTD cast and met with success—we saw plume signals in our particle and temperature sensors on the way down to the seafloor. The signals were still there, but weaker on the way back up. Later in the day, Jill analyzed samples from the plume for methane and confirmed that they followed the same trend.

That means we have a plume we can work with!

From Saturday night to Sunday morning we ended the day with an OFOS camera tow from north to south up the ridge to its summit. As we flew the camera up the hill, heading south, we found one area with a lot of discolored material on the seafloor that appeared to be falling downhill toward us, but the drift of the ice again meant that we had to change our course so that we couldn’t follow the trail straight upslope.

Moments later, however, our sensors picked up some temperature anomalies nearby, indicating we might be getting close to something. As we approached the very top of a lava flow (which was shallower than anything on our maps, much to the consternation of the OFOS watch team, whose job it is to keep the instrument from colliding with the seabed while, at the same time, flying it as close as they can to take good photos), I noticed that the arrangement of peaks surrounding a central depression at the summit of the seamount looked surprisingly similar to a site called Lucky Strike that I got to explore with an ROVin 1996.

With Antje’s permission we tried to guide the camera system in between the peaks to fly over the central “crater.” We couldn’t quite manage it, but just at the very shallowest point, we were able to see very fresh lavas and, in two photographs 20 seconds apart, little white animals of some kind—possibly amphipods—that were abundant at the site, but nowhere else in the vicinity. Could we have two different sites of venting?

Finally, 24 hours after I got up, it was time to crawl back to bed in celebration of an excellent first day of vent hunting.

What, you might ask, is happening with NUI? Good question. The team has been trouble-shooting all weekend and thinks they are getting closer to making another dive soon. Not on Monday, for sure, but maybe on Tuesday.

We have been at sea for just over two weeks now and, while we still have four weeks to go on the ship, we only have two more weeks to get any research done before it will be time to begin the long steam back to port.

There is another ice station all day Monday, which means it will be time to catch up on chores: get clean bed linens, do another load of laundry, and look through all the data from the first two days of vent sites. If all goes well and NUI is cleared to dive by the time of our daily science meeting at 4:00 p.m., I might go for a stroll on the ice before dinner.