So this expedition was supposed to be about Havre volcano exploding in 2012 and how the huge pumice rafts we all saw were formed. We will get to that eventually but so far, what we have found on the seafloor at the Havre is mostly new lavas. In fact, most of the world’s ocean floor is made of lava called basalt (plus a thin layer of sediment above that volcanologists like to ignore). Basalt lavas on the seafloor are commonly found in thin layers or in tube-like features known as pillow lava.

Although finding lava on the seafloor is no big deal, the Havre lavas are very different from the black basalt lavas and not at all common. They appear to be rhyolite. Rhyolite lavas have a chemical composition that makes them very sticky and stiff (viscous) when they emerge from the vent. Rather than flowing away, the pasty rhyolite lava piles up over the vent forming a mound (dome) that may grow to tens or even a couple of hundred meters high. If enough rhyolite comes out, then the dome may spread forming a short tongue of lava.

- Schematic of a rhyolite lava dome on the seafloor

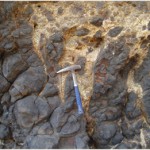

- Small spires and broken lava on the surface of a seafloor dome now uplifted on land in Nisyros, Greece.

- Broken rhyolite on the surface of a seafloor dome now uplifted on land in Cabo DeGata, Spain.

We have been using the autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry (a vehicle that can move underwater independently of the ship, collecting data) to make a very detailed map of the seafloor right at Havre volcano. The maps show new lava domes on the seafloor. We know for sure the Sentry features are domes because we have been down there with Jason, observed and sampled them.

So what do the rhyolite domes look like? They have an overall lumpy dome shape and close up, they look like big piles of jumbled up rock fragments, twisted blobs and jagged spires–in the words of one of the crew, “a big dump of sticky concrete.” Some of the spires are as high as 10 meters but only a few m across. All the rocky rubble comes from the sticky lava breaking up when it quenches and cracks up in the cold seawater. The broken pieces collect in talus around the edges of the domes and on the top. Most of the inside of the dome is solid rhyolite or broken just a little.

Only a few other rhyolite domes have been found and sampled on the floor of modern oceans because the rhyolite composition is not common. Rhyolite domes are reasonably common in volcanic areas on land. We know from the ones on land that sometimes growth of the domes is interrupted by explosions.