Since their discovery 40 years ago, deep-sea hydrothermal vents have attracted a lot of interest in understanding how life can thrive in the absence of sunlight. If you have been reading this blog, you probably know by now that this is supported by chemosynthetic microorganisms that can harness the energy from reduced chemicals in the vent fluids and fix carbon, which in turn fuel an amazingly diverse fauna. But this is only one side of the carbon cycle story. Once the carbon has been fixed into biomass, the fate of all this organic matter is still largely unknown.

For example, take the beautiful and dense patches of Riftia tubeworms. With a little help from their chemosynthetic symbiont friends, these animals can grow at the impressive rate of about 1 m per year. Notably, they can produce tubes up to 2 meters long and 4 cm in diameter, made of up to 30% of a sugar polymer (i.e. a poly-saccharide) called chitin. Additional sources of chitin at deep-sea vents include other tubeworms such as Tevnia or Ridgeia as well as the shells of the numerous crabs, squat lobsters and shrimps that thrive down there. However, there is no massive long-term accumulation of tubes and crab shells… Now what happens to all this sweet chitin?

A colony of Riftia pachyptila tubeworms near Teddy Bear, one the sites under investigation during this cruise. Note the patch of dead animals on the right.

As a microbiologist studying polysaccharide-degrading bacteria, this question has piqued my curiosity since my first cruise in 2014. Indeed, numerous studies on soil, coastal and freshwater environments have led to the conclusion that bacteria are major mediators of chitin degradation in nature. Yet, very little is known about who can recycle chitin at deep-sea vents, and how they do it. So, here am I aboard the Atlantis for this cruise, embarking on a treasure hunt for chitin-degrading microorganisms from different vent sites.

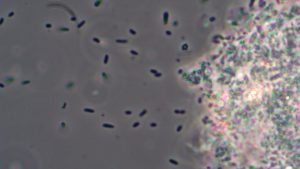

Riftia-associated bacteria (dark rods, about 3-5 µm in length) feasting on a chitin particle.

Every day, the submersible Alvin comes back from the deep world with new material for me to search for these unknown degraders: tubes of live or dead Riftia, crab shells, vent fluids, etc. Then, the strategy is simple. I use these samples as inoculum in a seawater-based culture medium containing only chitin as a carbon source, in hopes of “enriching” for chitin-loving microbes. After a few days of suspense, I check the cultures for growth using a microscope (quite a funny task on a moving ship!). I am very excited that my efforts so far have been rewarded with several growing cultures, showing multiple types of deep-sea vent bacteria feasting on chitin particles!

Back in my lab at the Station Biologique de Roscoff (France), I will further characterize these new isolates, to find who they are (i.e. their “taxonomy”), evaluate their abundance in the environment, study their physiology and understand how they degrade chitin. So, this cruise is the beginning of many more scientific adventures to come!