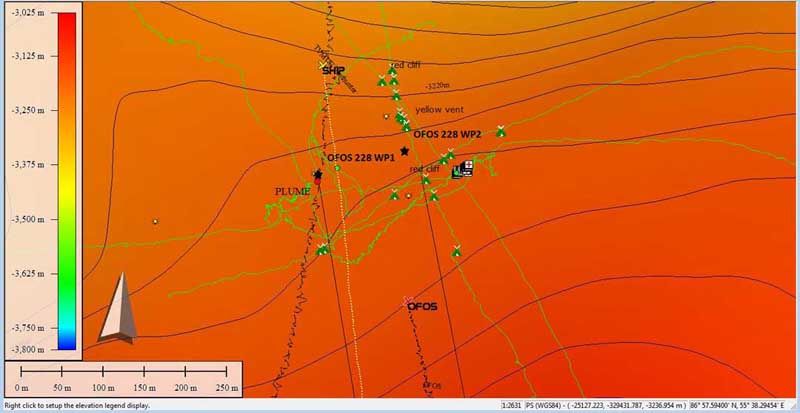

It could’ve been awesome. This screenshot of our navigation chart shows how we had OFOS lined up to scream right through the middle of our search area during the last night of our study at the Gakkel Ridge. Everything worked out great and we got the closest yet to finding the active vent source, but we never quite closed the deal.

Tuesday, October 11 – We’re heading home and it’s hard not to feel a little deflated. Maybe it’s because I haven’t slept enough the last day or two. Mostly, though, it’s because right up to the end we were getting ever closer to finding our vent, but then, at the very last minute, the weather and the ice defeated us. The balloon analogy from yesterday’s post, of us being swept away over the Arctic, applies very well.

After our successes with the CTD on Monday and a few hours’ sleep interrupted only by a pair of emergency drills for the crew (but the alarms still sound just as loud for us), it was up and back to work again with OFOS.

For our first attempt, we didn’t do too badly. Even though the wind and ice drift were fast, they were at least predictable and so we were able to line the ship and camera up so that, while travelling at double our preferred speed, we were able to pass right through the middle of our search area and chart new territory that we hadn’t visited before. Along the way, for four or five minutes of a five-hour deployment, we saw some of the brightest-colored mineral deposits and microbial mats that we had seen all expedition and, afterwards, we were able to download sensor data that revealed this same section of the seafloor also coincided with the first time all expedition we had intercepted warm, chemically enriched fluids close to the seabed.

Finally, we were on the trail—down at the seafloor—of the same signals we have been measuring up higher in the water column all cruise. We must have skirted right across the edge of the vent site, but because the wind and drift were sweeping us along, there was no way to double back. Once we were through the area that first time we were done. The only option was to pull the equipment out and get ready to go again.

Only now it was decision time: There were two more sampling operations to be done, in addition to time for one more camera run, but in what order? Because the weather was lousy, I proposed that we give the camera team a break, do everything else, and hope for better conditions at first light.

So we broke off work around midnight and my alarm didn’t go off until 5:00 a.m., when it was time to get up and collect one last CTD of plume-water samples that our colleague Massi could use to conduct microbial incubation experiments during the long steam home. Basically, our job was to lower the CTD as fast as we could into the plume, trip every bottle in the same place, and bring 240 liters (63 gallons) of t plume water back on deck so that Massi can determine what microbes are living in the plume and what they like to eat.

The cast worked out just as planned and we finished by 9:00 a.m. An hour later, we were in position and ready to put OFOS in one last time and had permission to stay in until it was time to leave at 3:00 p.m.

All started well and, just like Monday night, we had the ship and the camera lined up well and heading due north at (for us) high speed. We started a long way back to compensate so that, by the time the camera reached the seafloor one hour later we would be right where we wanted to be where we had seen the bright minerals and measured warm, chemically enriched fluid signals on the previous deployment.

For 30 to 45 minutes all seemed well, but then the wind veered from pushing us due north to blowing us northwest. Because we had started so far back, that now meant we were going way off target. Moreover, the ship was locked into a thick ice floe, so we had no option to move.

We were faced with two options: give up, or continue with the mission even though it wasn’t headed to the vent site. I argued that wherever we went we would see a part of our planet that nobody has ever seen before, so it was worth continuing. For the biologists who made up most of the team—and for me, too, if I am honest—the following two hours were a crushing disappointment because we only missed our target by a few hundreds of meters in the end and because it all played out in agonizing slow motion.

On the upside, the fact that we passed so close and just to the west of our target area will be very valuable when it comes to making a geological map of the site. We had previously passed to the north, south, and east and shown that in all of those areas, the venting is surrounded by extinct lava flows covered in a light dusting of sediment. So today’s exciting news is that this is true for the seafloor to the west of the hydrothermally active area, as well. Nobody knew that before today, so we can bank that as scientific progress.

But I would rather have found a new vent site.

We are now on our way south and west back toward civilization. Our calculations show that either it will take us three days, at an average speed of 5 mph (which is optimistic) or five days at an average speed of 3 mph to bust through all the ice and get to open water before the end of the weekend.

If we make good time, we plan to stop near Spitzbergen and do one last suite of scientific experiments before we leave the ice, including one more dive with NUI to study the ice-water interface, so we’re keeping busy preparing for that. In addition, as we get close to 80°N (which feels SOOOOOOO far south of here), and if we ever get any clear skies, we can look out for the Aurora Borealis—something I have never seen. That should be enough new things to look forward to in order to keep our spirits up for the next few days. And we have a cruise report to write, too.

But for the next few days we’ll probably be on silent running. The next time you hear from me, we should be within range of dry land for the first time in four weeks!